At the helm of his eponymous gallery for more than five decades, art dealer Bernard Jacobson has championed some of the greatest artists of the 20th century through both the gallery’s exhibition program as well as his own research and publications. One such artist at the forefront of Jacobson’s endeavors is Robert Motherwell—an artist who was at once a major player in Abstract Expressionism and the New York School in the middle of the last century and whose singular work defies easy categorization.

Recently, Jacobson penned an open letter on the subject of Motherwell, outlining his significance and influence both in his time and still today, as well as offering insight into the artist’s oeuvre and continued relevance from the vantage of Jacobson’s expertise—expertise garnered from decades of close study and research. The letter acts as a complement to the gallery’s three-part exhibition series on the artist, which commenced May 11 with “Robert Motherwell: Prints,” on view through June 3, 2023. This exhibition will be followed by a presentation of Motherwell’s collages and works on paper, and, finally, a show featuring a selection of his paintings.

We reached out to Jacobson to learn more about the gallery’s and his own current focus on Motherwell, and how he sees Motherwell’s work continuing to influence contemporary painting.

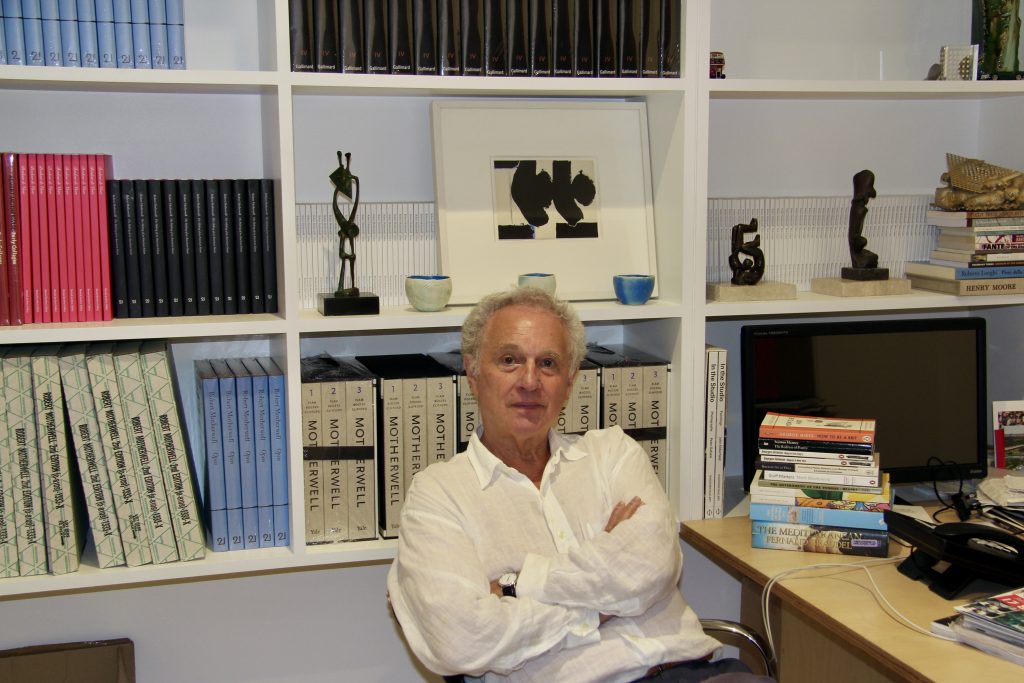

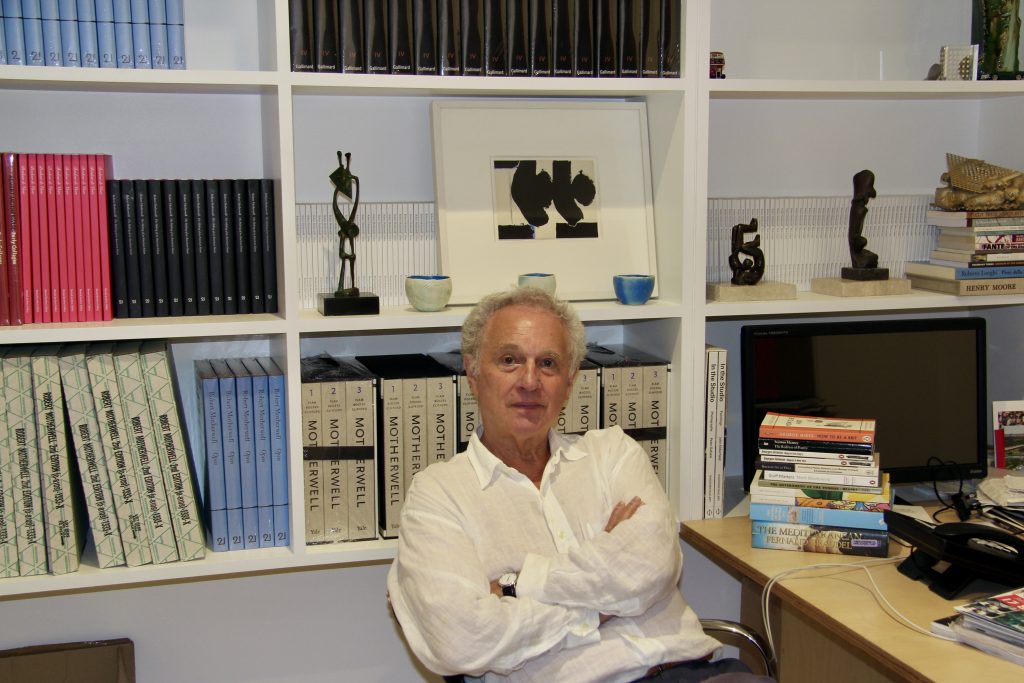

Bernard Jacobson with works by, and publications on, Robert Motherwell. Courtesy of Bernard Jacobson Gallery, London.

The gallery is in the midst of presenting its three-part exhibition celebrating the life and oeuvre of Robert Motherwell. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired the production of this show? Why now?

I have found there is a significant falling away of interest in Robert Motherwell in America, and he is an artist who I believe is perhaps the greatest the huge country of America has produced so far. As the East and Europe seem to find more and more significance in this artist and are keen to own his works, from prints and collages to his biggest paintings, I find much less sense of fascination and wonder coming from Americans. We ourselves have to contend with the fads and fashions that now dominate the art market, plus the fairly recent obsession with what is called branding, the need to acquire the work of the latest art star or monumental name from our recent past, in this case, Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, both of whom I personally find less substantial in the end product—the painting itself—than Motherwell. But, sadly, once upon a time, people would say that money speaks. They are out of date, and now it shouts. And the gentle folk who advise the buyer don’t seem to have much grasp on the huge subject of art.

With each part dedicated to the various mediums Motherwell engaged with, can you say if you have any favorite works that are or are going to go on view?

I love every work Robert Motherwell added his wonderful signature to, from the tiniest drawing inspired by James Joyce’s Ulysses to the miraculous gigantic paintings in the “Elegy” or the “Open” series. When you realize that you may be as significant as Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso, and Henri Matisse, you feel the huge weight placed on your shoulders, and you don’t sign until you are sure.

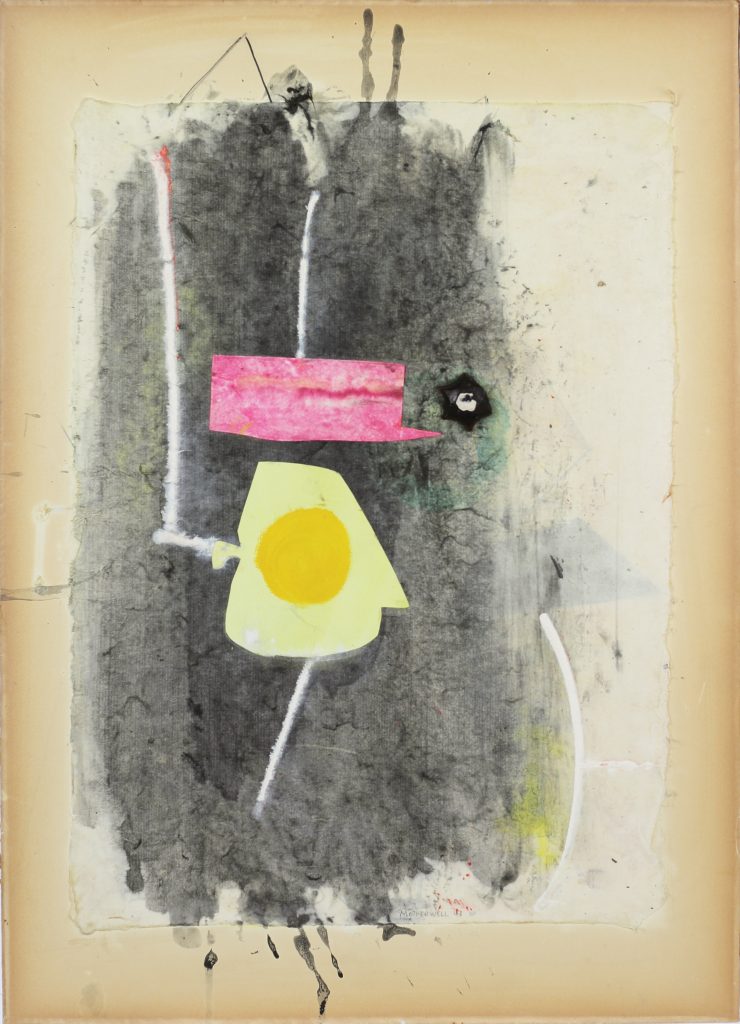

Robert Motherwell, The Mexican Window (1974). Courtesy of Bernard Jacobson Gallery, London.

Though you were already an expert on Motherwell, over the course of producing the exhibition, did you gain any new insights or were you surprised by anything you didn’t know before?

Of course, there are always new insights, just like when you are confronted by a great painting by Piero della Francesca or Nicolas Poussin, or Paul Cézanne.

You’ve described Motherwell as the “odd man out” within the context of the Abstract Expressionists. Can you expand on this?

I want to think this is covered well enough in the letter I sent to the art world. I may perhaps add that today’s collector should try to come to art with an open mind and find his or her own personal passion, rather than those of the herd of independent minds, as the great American critic, Harold Rosenberg, so succinctly put it. Sadly, we barely have art critics any longer, so you have to work it out for yourself. But that surely is the thrill and the necessity.

Bernard Jacobson, California (1959). Courtesy of Bernard Jacobson Gallery, London.

What do you hope visitors of the exhibition in all its parts take away with them?

Simply that Robert Motherwell should not be understood too quickly. He—more than any recent artist—is worth your time and your devotion.

On a personal level, what draws you to Motherwell’s work?

On a personal level, I’ve found in Motherwell a world that was way beyond his friends and colleagues, such as Pollock and Rothko. I admit that De Kooning was a problem for me because I find him an equal to Motherwell, although he’s coming from quite a different direction. Their ambitions and aims were so far apart, although they were both loosely fighting the same aesthetic battle, at least in general. But the great intellect and profundity are virtually on par. I would say that these two are practically equals. But I decided to study and study and study Motherwell, as I have done for 20 years now. He has the magic, the depth, and the power in the palm of his hand, and he cherishes and respects the exceptional gift he has been given. De Kooning is, as I say, an equal. it is simply that Robert Motherwell speaks to me a lot more clearly and deeply, and it touches my heart so much more!

Robert Motherwell, Elegy to the Spanish Republic No. 60 (1960). Courtesy of Bernard Jacobson Gallery, London.

How would you describe Motherwell’s legacy within the context of painting today?

Motherwell’s legacy is quite simply enormous. Thousands of artists (other than just Pierre Soulages, who I mention in my letter), have been enormously moved and inspired by the man and his work. I see his influence all the time and everywhere. I have seen it across America, but just as strongly in the east and the European countries. Once, when I was Kenneth Noland’s dealer he said to me, “we all thought the world of Jackson, but we couldn’t use him.” I now understand why Motherwell meant so much to Noland. It is his massive brainpower and intellect, something that eluded all the others in his circle. My job is nearly done on Robert Motherwell. I moved on to Georges Braque three years ago. But Motherwell will remain with me in a permanent position of excellence, greatness, and generosity of spirit. In fact, my next book, which I hope will come out next year, is a series of short and sweet episodes set in Paris—one which I am very happy with, is of the elder statesman, Braque, meeting up with the youngster, Motherwell, at le Deux Magots. I don’t know how these crazy ideas come into my head, but I am so pleased that they do, so deep in my subconscious!

Robert Motherwell, Black with No Way Out (1983). Courtesy of Bernard Jacobson Gallery, London.

Learn more about Bernard Jacobson Gallery’s exhibitions on Robert Motherwell here.