Gallery Network

7 Questions for Gallerist Christian Berst About How He Put Art Brut on the Map

Catch the gallery's presentations of Éric Benetto at Paris+ by Art Basel and Jorge Alberto Cadi at Paris Photo.

Catch the gallery's presentations of Éric Benetto at Paris+ by Art Basel and Jorge Alberto Cadi at Paris Photo.

Artnet Gallery Network

Art brut, a phrase coined in the 1940s by French artist Jean Dubuffet, identifies a class of art that operates outside of what he termed “art culturel,” or fine art that is beholden to academic and cultural prescriptions and principles. Since its inception in 2005, Christian Berst has placed art brut artists at the forefront of his Paris-based gallery’s program and proven that the genre is as potent and relevant today as when it was first identified by Dubuffet.

This week, Christian Berst Art Brut will be showing the work of Éric Benetto at Paris+ by Art Basel (October 20–23), and next month will exhibit work by Jorge Alberto Cadi at Paris Photo (November 10–13). Ahead of these fairs, we spoke with Berst about his path to founding his eponymous gallery, how the reception of art brut has changed 17 years later, and what we should know about the forthcoming Cadi and Benetto presentations.

Christian Berst Art Brut opened in 2005. Can you tell us about your journey leading up to the opening of the gallery? How did you first become interested in the arts?

It’s a story of epiphany, of revelation. Although I was already an art lover, all I knew about art brut was Dubuffet’s texts. Nothing predestined me to open a gallery; I come from the literary web and publishing. So it was logically thanks to books that I discovered art brut 30 years ago—institutions almost never showed it at the time. Fifteen years after this discovery, and observing that people were convinced by art brut when they saw it, I decided to become an emissary by creating this specialized gallery.

Since you started, what are some of the biggest lessons you’ve learned? Do you have any advice to young or new art gallerists?

The poet René Char wrote: “Impose your luck, clutch your happiness, and go towards your risk. By looking at you they will get used to you.” I always have this precept in mind. But in reality, everyone must look for the meaning of what they want to do, what motivates them. And then you have to be unwavering in your determination, you have to be stubborn. Remember that it is not an exact science.

Though the gallery also shows well-known artists, it has developed renown for its specialization in outsider art, or art brut. What are some of your guiding principles as an art dealer? How is this reflected in the art and artists you represent?

Let me be precise: I show art brut, not outsider art. You don’t confuse the sun with the solar system. The sun is art brut: the art of otherness, of individual mythologies outside the usual art circuits. Outsider art is the solar system, which contains the sun, but covers many other categories, folk art, intuitive art, visionary art, self-taught, etc.

A lot has changed in the gallery world over the past years. Do you have any predictions for the future of the art market? Are there any trends or leanings that you find particularly exciting or intriguing?

Art brut is now “on the map”: it has regular presence in the official selection of artists for the Venice Biennale and numerous acquisitions by museums such as MoMA, the Met, the Centre Pompidou, etc. Several major exhibitions are being prepared in international institutions—to say nothing of market phenomena, such as the annual sale at Christie’s New York. More and more collectors and the public are interested.

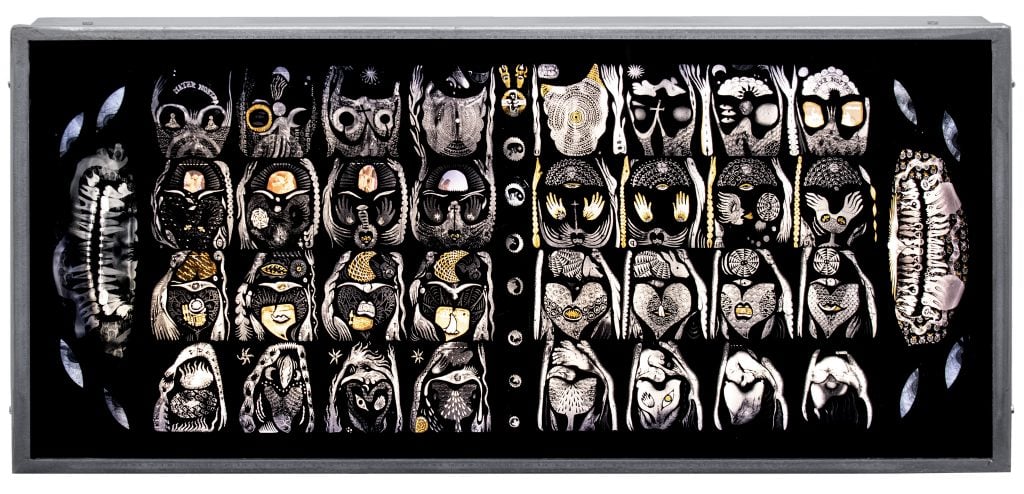

Éric Benetto, Untitled (2021). Courtesy of Christian Berst Art Brut, Paris.

This week, you will present Éric Benetto at Paris+ by Art Basel, and next month Jorge Alberto Cadi at Paris Photo. Can you tell us a bit about each artist? Is there a specific facet of their work that you are particularly drawn to?

It should be noted that these are contemporary brut artists, discovered and defended by the gallery for sometimes more than a decade. Benetto is a mystic before being an artist. He works for months on X-rays that he then assembles into one image, onto which he draws dizzying patterns with pen and ink. When illuminated from behind, they are fascinating works of great spirituality. They have already been shown in major contemporary art collections, but Paris+ by Art Basel is the first time this highly original work will be shown to such an international audience.

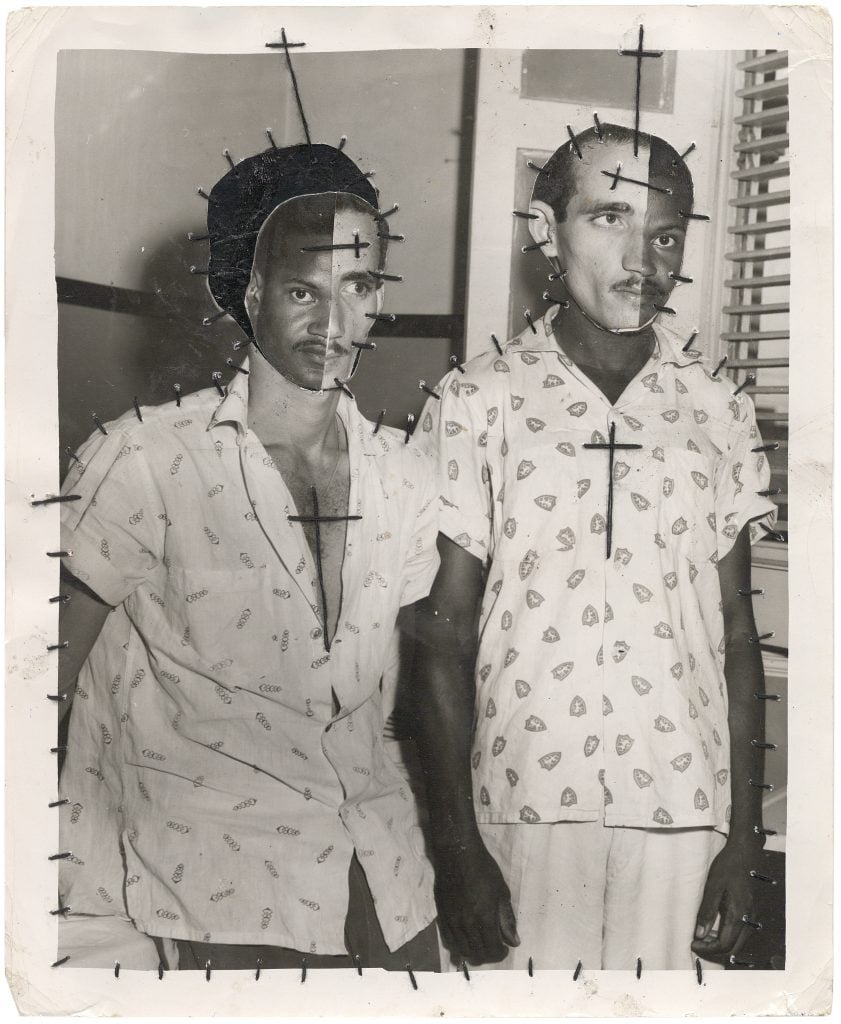

As for Jorge Alberto Cadi, I discovered him in Cuba six years ago, and thanks to his first exhibition, our publications, and the many loans we have made, his work has since entered the Pompidou. A significant body of his work will also be shown at the end of this year in Brussels as part of the second part of Photo Brut, which will be presented at the Botanique and at the Centrale for Contemporary Art.

Cadi has worked for a long time in the greatest secrecy; he never imagined that his work would end up in a gallery, let alone in major museums. His work mixes existential concerns with the memory of those who have disappeared, especially Cuban exiles. His material is made up of old photos and discarded objects. He assembles, sews, cuts out, overloads with quotations. He is a cross between the Andy Warhol of the stitched photographs and the Christian Boltanski of the “Inventories” series.

He is also a member of the Larivière Foundation, which will open in Buenos Aires and present one of the largest collections of Latin American photographs.

Jorge Alberto Cadi, Untitled (2020). Courtesy of Christian Berst Art Brut, Paris.

Of all the shows the gallery has presented, do you have any favorites? Or perhaps instead found the most memorable?

This is a very difficult question. I am divided between exhibitions of my numerous discoveries of contemporary brut artists around the world, which is the real DNA of the gallery, but also some exhibitions of the great “classics” of modern art brut that I have been proud to bring together. All of these—and the nearly 100 bilingual catalogues published—have contributed, patiently, over 17 years, to making the gallery both a reference in its field and a place for reflection and exchange. Thus, the Bridge, our second space, offers curators the opportunity to create a dialogue between art brut and other categories of art. This is very enriching.

A new chapter in the history of art is being written, which is very rare. I am very happy to contribute to it.

If you were not a gallerist, what would you be doing?

Any function in the service of an art as essential as art brut would suit me. Editor, writer, curator, lecturer. I am already a bit of all of these, but I lack the time to dive into each of these activities as I would like to.

But as Confucius said: “We all have two lives, the second begins when we realize we have only one.”