Gallery Network

7 Questions for Canadian Artist Nick Rooney on His Unexpected—and Emotive—Wildlife Portraits

The artist's most recent body of work is currently on view in "On the Other Side" with Loch Gallery, Calgary and Toronto.

The artist's most recent body of work is currently on view in "On the Other Side" with Loch Gallery, Calgary and Toronto.

Artnet Gallery Network

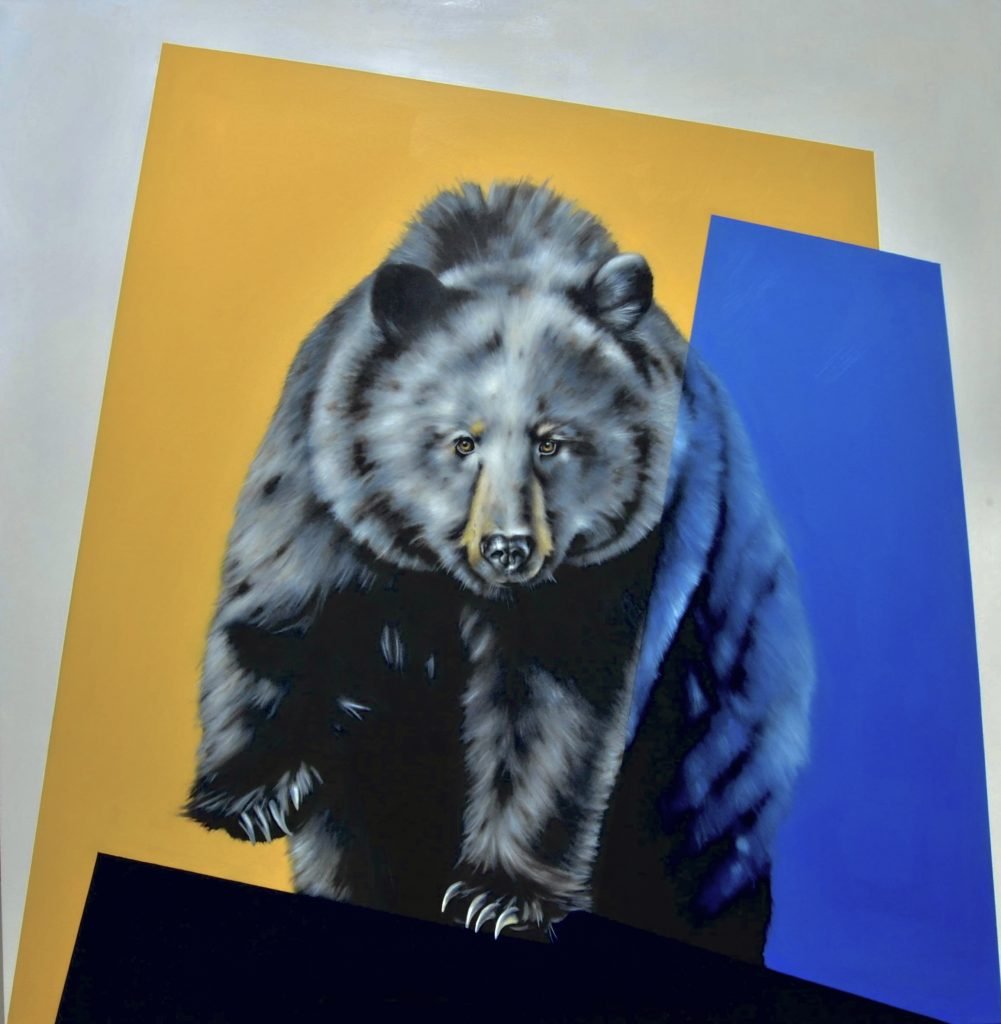

Canadian artist Nick Rooney (b. 1989) has a practice centered on the boundaries between realism and abstraction, exploring the ways in which these delineations are concrete or, conversely, malleable. Further drawing inspiration from Western art history and the natural world around him, Rooney has created his own artistic lexicon to engage with ongoing explorations of the formal elements of painting, and the ways in which apparent contradictions—such as volumetric forms and flat geometric planes—together can lead to new relational understandings.

Currently, the artist is the subject of a solo show with Loch Gallery in Calgary and Toronto, “Nick Rooney: On the Other Side,” which is on view through April 29, 2023. Here, Rooney’s work focuses on the relational tensions that arise when elemental oppositions are employed. Though featuring nuanced portraits of different species of animals in each painting, the depictions operate primarily as compositional devices to delve into the tenets of painting and experiment with ideas of perceptual space.

We caught up with Rooney to find out more about the origins of his ongoing painting explorations, and how the current exhibition fits within his practice.

Nick Rooney, On the other side (2023). Courtesy of Loch Gallery.

Can you tell us a bit about your background? How has your work evolved into the style it is today?

I completed my BFA in painting in 2012 with the feeling that I had no idea how to paint. At the time, I wanted to be Rembrandt, and like most young painters had no idea what that meant. After much research and reaching out to oil painters whom I admired, I began a self-directed study into the materials and techniques of oil painting. After eight years of studying, creating, and exhibiting paintings, I moved to the U.K. to pursue my M.A. at the University of Art London. My graduate research and the proximity to some of the best museums sparked my interest in the combination of both classical realism and minimalism.

Your show “On the Other Side” is opening at Loch Gallery. Can you talk about the works and themes in the exhibition?

In recent years, liminal space is the theme that most often comes up in my work. It is defined as the space that sits between the inner and the outer, the subjective and the objective, reflection and action, and stimulus and response. In “One the Other Side,” I began to explore relationships in this third space, I removed natural colors and reduced the palette to monochrome to focus on the relationships both in color harmony and mutualism. The search for balance both in geometric forms and empty space removes the animal subjects from any traditional setting and context and sets up a dialogue to create and explore an environment rooted in the transition where tension, pressure, and struggle often reside.

Nick Rooney, Nature of Attraction (2023). Courtesy of Loch Gallery.

What do you hope visitors of the show take away with them? What do you hope most to convey?

I hope that in breaking up the picture plane with hard lines in contrast to the much softer realism, visitors start to question what’s going on. I personally don’t consider the work to be wildlife painting; yes, the subject is an animal, but I am more interested in the emotions, thoughts, and parallels that we share with these animals. For example, in Nature of Attraction, rams are featured out of context, they no longer collide together but rather the same action with the addition of a geometric shape looks as though they are working together to flip the shape. Their relationship for me generates ideas of partnership, teamwork, struggle, and balance, and I hope that the audience feels the same.

How does this exhibition continue or diverge from the body of work that was shown in your solo exhibition last year, “Nature’s Edge”?

“Nature’s Edge” was my first attempt to establish a visual depiction of this third liminal space. I used both naturalistic colors and monochrome. I focused more on the natural history and the symbolism attributed to animals. I chose animals such as a fox for their ability to adapt, they can move through spaces coming out successful on the other side. While living in London, England, I had a family of foxes living outside my kitchen window. I got to see first-hand the fox thrives outside of conventional settings. “One the other side” pairs animals and color harmony for the first time, the yellow wolf following a blue jay. I am really looking to create and highlight interactions.

Nick Rooney, The Listener (2023). Courtesy of Loch Gallery.

What is the role of—or how does your location in—Southern Alberta affect your work or your perspective?

I can’t say Southern Alberta specifically, as the initial idea came from my time as a graduate student in the U.K. The move back to Canada was a huge shift though, previously I was working with the collection of the British Museum and more still lifes. Living briefly on the West Coast allowed for daily interactions with herons, peacocks, and an array of other birds that served as a reminder of the foxes from my old flat. Living in Canada and having the ability to travel within has given me a unique perspective as we have a diverse range of wildlife, and those interactions greatly affect my work.

What does your creative process look like, and where do you most commonly find inspiration? Are there any significant influences from other artists or movements?

The creative process for me comes in many steps. I often see an animal, object, or color relationship that creates the first spark. I work on an iPad creating shapes and colors—more play than anything, but it has built me a great catalogue of potential shapes to work with. Almost every animal is then Frankenstein-ed together from several sources, I spend a lot of time trying to get the anatomy and the pose correct. Occasionally, I sculpt small maquettes, which give me more visual information. Once I have an image that excites me, I build the stretcher and start the drawing and then the painting process. I am very inspired by painting, the amount of skill that I see daily on platforms like Instagram is a daily reminder that I must work harder. The Canadian painter Ivan Eyre has become a recent favorite for his color, skill, and range as a painter.

Nick Rooney, Matriarch (2023). Courtesy of Loch Gallery.

Can you talk about what you are currently working on, or are planning to work on next? Are there any themes or subjects that you hope to engage with that you haven’t yet?

The question of what next is always on my mind. I don’t lack inspiration and as I spend more time in the studio, I’m starting to have the privilege of working on more of these ideas. I’m moving into a larger studio after this show so right away I think about scale and how big I can go. I plan to go back and do a few more still lifes, I have a few images that I can’t seem to get out of my head, so they have to become paintings. Shaped canvases have been on the back burner for a while now, I would love to take the geometric shapes that are currently on rectangle supports and push that concept. Dutch-inspired still lifes on shaped geometric panels are a concept that I will put some time into and of course, I love painting these large animals so I’m sure I have a few of those on the go as well.

“Nick Rooney: On the Other Side” is on view at Loch Gallery, Toronto, through April 29, 2023.