Gallery Network

7 Questions for Senegalese Artist Soly Cissé on How the Rise of the West African Art Scene Is Reshaping Local Communities

The multidisciplinary artist is gearing up to show at several international art fairs this year.

The multidisciplinary artist is gearing up to show at several international art fairs this year.

Artnet Gallery Network

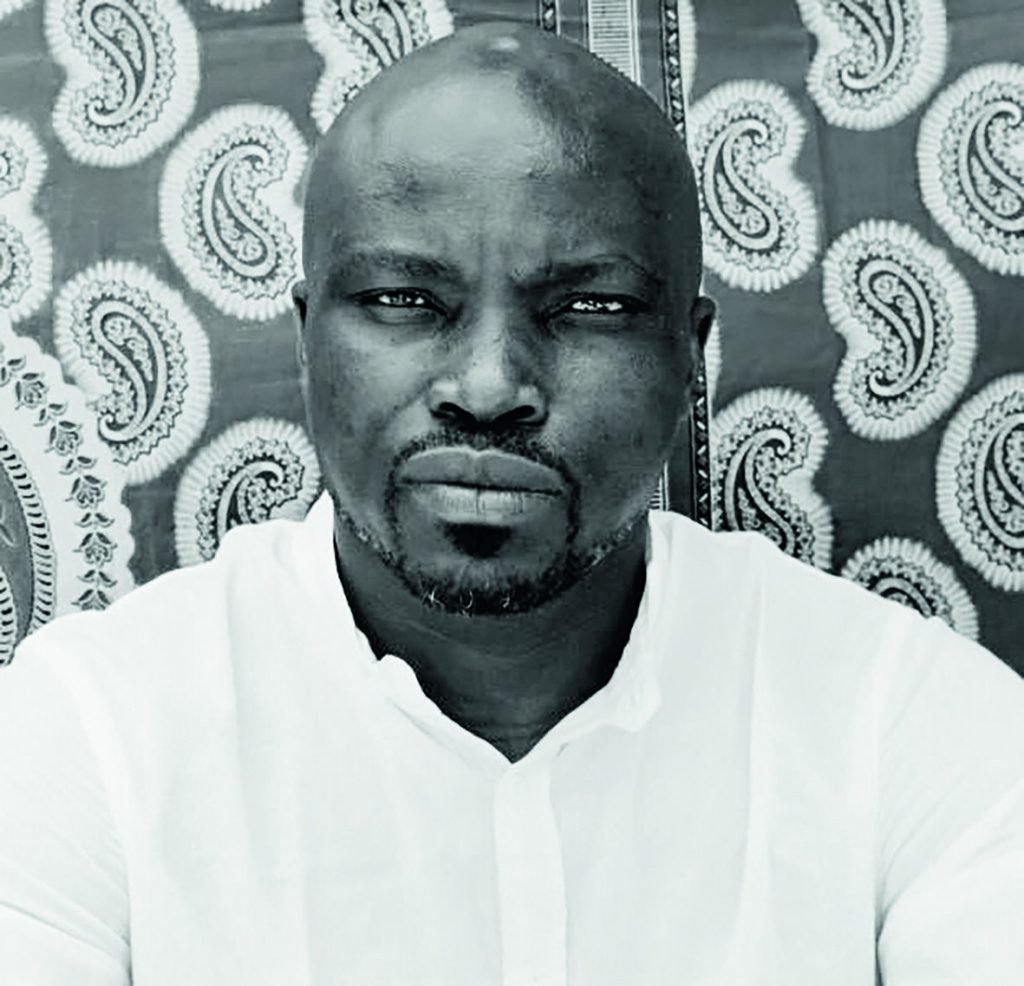

Hailing from Dakar, Senegal, contemporary artist Soly Cissé maintains a practice unrestricted by disciplinary boundaries. Working across painting, sculpture, drawing, and assemblage, the context and themes of his work are deeply rooted in his life growing up in Dakar as well as the socio-political history and present of Senegal. His earliest works, made as a child, used radiographic images brought home by his father, and the compositional and thematic elements of the radiographs—comprised of light and shadow—remain relevant in his practice today.

Having studied at the School of Fine Arts, Dakar, and undertaken residencies abroad, Cissé’s practice is born out of a strong foundation of contemporary art and art world knowledge—which has also inspired the artist to actively mentor and assist regional emerging artists. From organizing workshops for young African artists to explaining the “rules of the game” to first-time fair participants, Cissé has established himself as not only a leading contemporary artist but an influential figure in the promotion of African art on the whole.

We reached out to Cissé to learn more about what he thinks about the present and future of the African art scene and the inspirations behind his work.

Soly Cissé, Sindakh (2013). Courtesy of Sulger-Buel Gallery, London.

Working at the forefront of Senegalese and African art scenes, from the perspective of your multi-decade career, what are some of your observations or predictions about increasing international interest in African and African Diasporic artists?

African art is on the right track, taking over the center stage. With such watershed exhibitions as “Les Magiciens de la Terre” (“The Magicians of the Land,” Paris, 1989) and Africa Remix (Dusseldorf, Paris, London, Tokyo, Johannesburg, 2004–07), as well as dedicated art fairs such as 1:54 and AKKA, African art starts to get its fair share of attention. Some artists start to emerge and stand out on the international art scene, also thanks to some big fans and supporters such as the galleries Sulger-Buel Gallery, Magnin, Chauvy, and others, their hard work brought fruits in the long term.

There is clearly a fashion aspect, Africa needs to capture this opportunity and transform it into a permanent interest in its arts scene. The presence of one’s works in key art institutions brings recognition, for example when my works entered the permanent collections of Centre Pompidou in Paris.

What is your viewpoint on the evolution and transformation of the African art scene overall considering this rising international interest, specifically in Senegal and West Africa?

The first edition of the Dakar Biennale was organized in 1992, it is only from that date that we can speak of contemporary art in Senegal and in West Africa. Since its beginning, the Dakar Biennale was threatened to be put on hold numerous times, but passionate supporters allowed it to go on. It is important to ensure the continuity of this event, if it ceased to exist, it would entail negative consequences for contemporary art in Senegal and West Africa. Perhaps its continuation should rely more on private patronage in the future because government support can be questioned, due to rampant political instability in this part of the world.

There are many other initiatives, for example in Morocco, Tunisia, and elsewhere, collaborations between countries, institutions, and art fairs. Many of these new initiatives emerge on the local level. A good example is an ambitious project of itinerary exhibition launched by Galerie 38 from Casablanca, which will be shown in several African capital cities.

There is a lot of hope and expectations, numerous local actors want to make things happen at their level. However, overall, the African public ignores important artists that are being recognized in Europe, while they remain unknown in their own countries. Hence the importance of cultural exchanges, to raise awareness, and to demonstrate that arts and culture can have a great positive economic impact, that it can be a source of development for these nations. In parallel, it is needed to reinforce artistic education in Africa. On the positive side, there are more and more art collectors in Africa, benefiting of complicity from Western institutions and collectors.

Your work frequently incorporates human and animal hybrids, as well as elements of African tribal art. What is the inspiration and meaning behind these elements?

I am greatly inspired by traditional African culture, including tribal arts such as African sculpture. African artists are very lucky to have such a rich artistic and cultural heritage, Africa is full of great artistic and cultural traditions. African tribal art carries a mystical dimension, for example, animals represented in sculpture have a specific symbolic meaning referring to war, love, etc. It is a reflection of African mythologies, where animals appeared as religious and mystical symbols. Great unknown African artists of the past knew these symbolic meanings, why not get inspiration from these ancient artworks?

For me painting is like a ritual, when I paint, I try to understand our existence, the elements that surround me. However, it is a spontaneous process, disconnected from commercial considerations and judgments of others. I have always conveyed these important elements in my work, I am not the one who created these beings—they were already there, they called upon my attention. My spontaneity and artistic freedom allowed me to express my ideas using these images.

Many collectors and followers of your work know you for your work as a painter—but sculpture is also an important facet of your practice. What are some key differences between your painting and sculpture practices?

My artistic freedom encouraged me to experiment with sculpture, hence the series “Gladiators.” I am against any limits between media, I believe it reflects the dynamics of African art overall. African artists must confront the international art market. It also applies to the Dakar Biennial which must welcome international artists.

The series “Gladiators” is a reflection of my thinking around Senegalese wrestling, a traditional sport of my country that has become more violent in recent times, apparently to respond to the expectations of the public. This reflects a societal change, the Senegalese society becoming more violent, in my opinion. In my sculptures, I compared the wrestlers to antique gladiators, to testify about this change.

Recently, for the first time, I created a sculpture for a public space. I had to forego my usual subject matter and find a discourse and a language that can be shared among the community. In the city of Evreux, France, trees had been removed from the Place des Peupliers, I wanted to bring trees back but in the form of a sculpture made in bronze. Entitled Sacred Wood, it refers to a space where people of the community gather in Africa. I have created a symbolic space that conveys the ideas of nature and of a space of encounter and dialog. I have also involved local children, getting inspiration from their drawings, some of which were included in the actual sculpture in low relief.

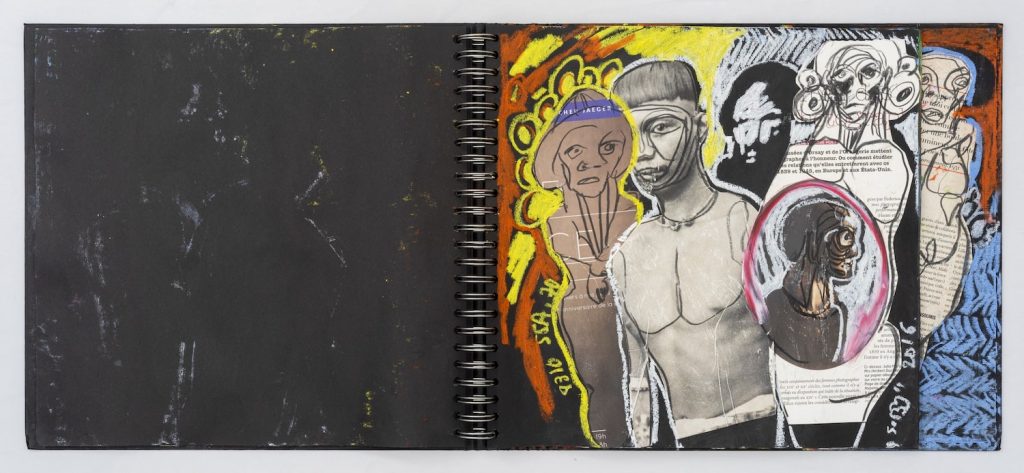

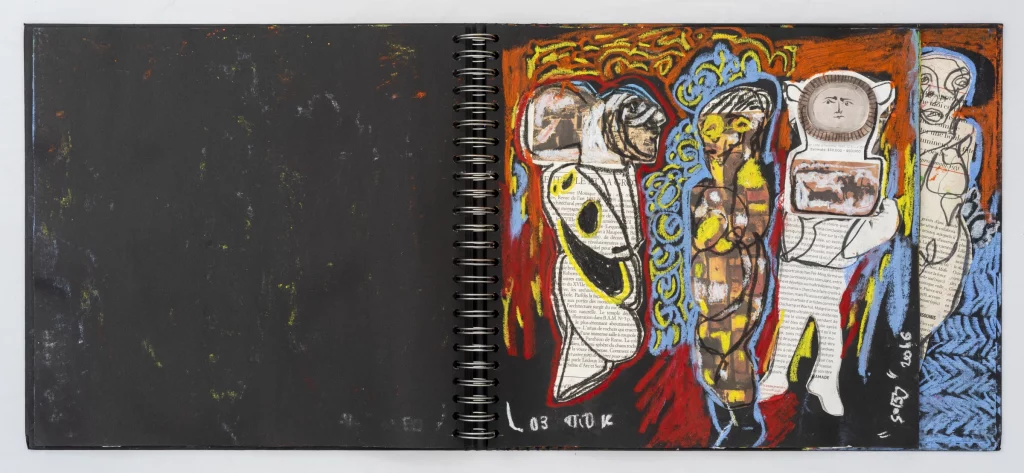

Soly Cissé, Black Book V (2016). Courtesy of Sulger-Buel Gallery, London.

Black Books (2016), an experimental project involving collage, was seemingly a pivotal moment in your work, shaping your style and subsequent work. Can you describe how Black Books affected your practice?

I had the idea for collage while browsing magazines offered on long-haul flights. Initially, I made drawings on these magazines, leaving them for the following travelers to enjoy. In fact, I love drawing, I spend a lot of time drawing. Another source of inspiration was the X-ray pictures made by my father, a radiologist, which gave me the idea of drawing on black background. When I found an album composed of black pages, I purchased it and filled it with collages, cut out of magazines, drawing over them. Such an album is like a small portable gallery!

For me being an artist today is to shake up the rules of the art world. Even in my work with colors, I am trying to find novel colors that could be seen as shocking. I consider that an artist has to express his spontaneity and not try to control his creative process. The incredible force of such artists as Basquiat, without any artistic training, was to challenge all the existing limits.

My artistic freedom allows me to experiment with various media, such as sculpture and collage. Consequently, the collages contained in the Black Books, which certainly was an experimental project, impacted my painting in the long run.

Soly Cissé, Black Book V (2016). Courtesy of Sulger-Buel Gallery, London.

Are there any specific artists or movements—contemporary or historical—that you have particularly influenced your work?

I believe in my great capacity of digesting various influences. We must acknowledge that “influence” is the rule in art, it is part of the “truth” about art. In my opinion, acknowledging the influences is a positive thing, although some artists prefer to disprove them. I look towards Picasso, Modigliani, Basquiat, Giacometti. These artists were all inspired by preceding generations of great artists, they were also very much influenced by African tribal art, and beyond. Hence, we are all influenced by whole segments of art of the past. It is important to use these influences with intelligence and without abusing them. If it results in developing a novel idea, past examples are used to positive ends.

Can you tell us about what you are currently working on, or any future projects you have planned?

In my projects, there is a solo exhibition in Casablanca, and taking part in the AKKA Paris art fair, and in 1:54 Paris and Marrakesh art fairs.

Learn more about Soly Cissé with Sulger-Buel Gallery, London, here.