Art World

8 Things You Should Know About Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Salvator Mundi,’ His Holy Mona Lisa

The painting gave da Vinci experts goosebumps at first sight.

The painting gave da Vinci experts goosebumps at first sight.

Rachel Corbett

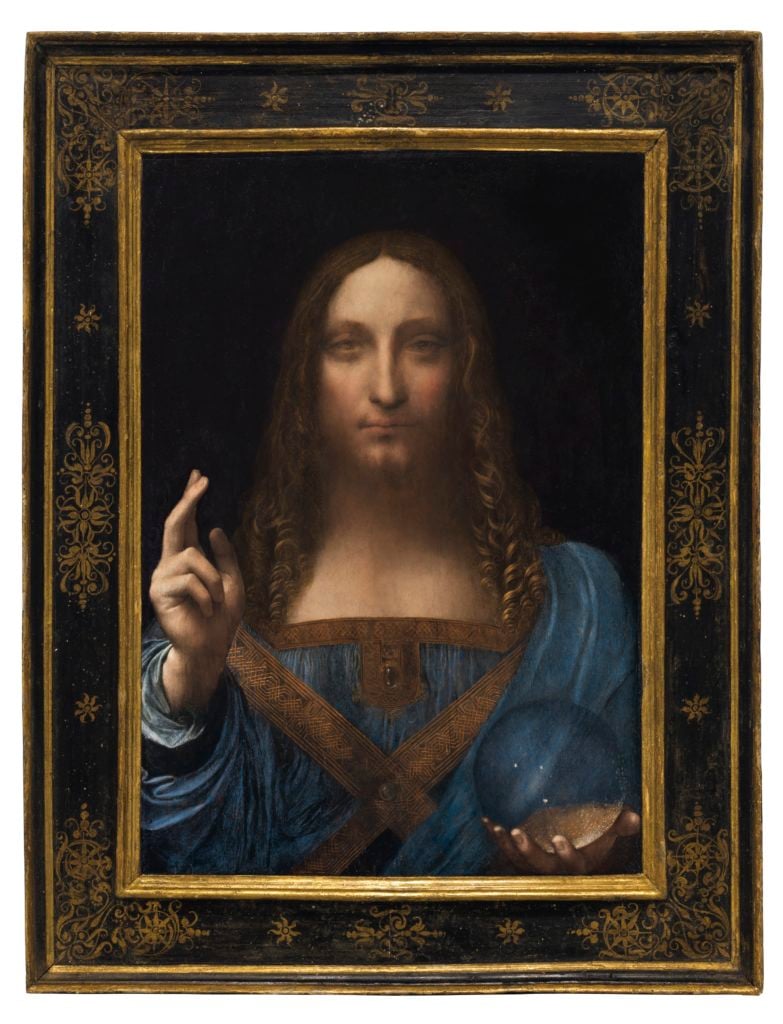

With the news that Christie’s will sell Leonardo da Vinci’s long-lost painting Salvator Mundi next month for an estimated $100 million, one might wonder what makes this soft, ethereal portrait of Jesus Christ such a masterpiece? Here are a few things to know about what makes the painting so special.

Some experts believe that Leonardo originally painted the work for the French Royal family, and that Queen Henrietta Maria brought it with her to England when she married King Charles I in 1625. The work remained part of the royal family’s possessions until 1763—and then went missing for nearly 150 years. It reappeared when it entered the collection of the Virginia-based Sir Frederick Cook at the turn of the 20th century and appeared on the market again in 1958, at an auction where the painting, attributed to one of Leonardo’s studio assistants, sold for a mere £45 ($72).

It didn’t surface again until 2005, at an American estate sale, when New York art dealer Alexander Parish purchased it for another bargain price of $10,000. Then, he and a consortium of fellow dealers sold it to “freeport king” Yves Bouvier in a private Sotheby’s sale for a cool $75 million–80 million in 2013. That same year, Bouvier turned around and sold it for $127.5 million to the Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev, who is now offering it for sale at Christie’s.

Since it resurfaced, the painting has been involved in complex and overlapping legal battles. Most famously, it incited the ongoing feud between Dmitry Rybolovlev and his former art advisor Yves Bouvier. Soon after the Russian billionaire bought the work for $127.5 million, he was surprised to read in the New York Times that the picture had recently sold for almost $50 million less than he paid. The realization that he had bought the painting at such a high markup set off a legal battle over Bouvier’s alleged overcharging that continues today. (A representative for the Rybolovlev family trust says the Salvator Mundi sale “will finally bring to an end a very painful chapter.”)

The group of dealers who originally sold the work also threatened to sue Sotheby’s over the difference between the price Bouvier and Rybolovlev paid. Meanwhile, Sotheby’s has sought to insulate itself from any lawsuits by asking the court last year to clarify that it is not liable for any losses suffered by the sellers.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi. Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd. 2017.

By the time conservators finally got their hands on it in the 21st century, the walnut panel had split and was patched together with stucco and glue. One shoddy restorer coated it in a graying resin. It had even been repeatedly painted over. “It was a wreck, dark and gloomy,” reported ARTnews.

“’We were given a day to examine it and it was all the time we needed–we could tell at once that it was a work by da Vinci,” art historian Pietro Marani told the Daily Mail in 2011.

Renaissance scholar Martin Kemp also had a goosebumps moment. “It was quite clear,” Kemp told Andrew Goldstein. “It had that kind of presence that Leonardos have. The Mona Lisa has a presence. So after that initial reaction, which is kind of almost inside your body, as it were, you look at it and you think, well, the handling of the better-preserved parts, like the hair and so on, is just incredibly good. It’s got that kind of uncanny vortex, as if the hair is a living, moving substance, or like water, which is what Leonardo said hair was like.”

There’s still debate about whether Leonardo painted it in Milan in the 1490s, while working on The Last Supper, or in Florence after 1500, while working on the Mona Lisa.

When the painting debuted to the public at the National Gallery in 2011, tickets sold out within one week, with scalpers selling them illicitly for as much as $400 apiece. But Guardian art critic Adrian Searle did not seem as impressed with Leonardo’s representation of Christ, noting that he had “the glazed look of someone stoned.” He went further: “You can imagine the raised fingers holding a spliff. Once imagined, the image won’t go away.”

![Christie's unveils Leonardo da Vinci's Salvator Mundi [pictured] with Andy Warhol's on October 10, 2017 in New York City. Photo by Ilya S. Savenok/Getty Images for Christie's Auction House.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2017/10/salvator-mundi-leonardo-christies-1024x680.jpg)

Christie’s unveils Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi [pictured] with Andy Warhol’s on October 10, 2017 in New York City. Photo by Ilya S. Savenok/Getty Images for Christie’s Auction House.

The work is one of only 20 paintings known in existence by the artist, including his Benois Madonna, now housed at the Hermitage, which is the second-most-recent Leonardo discovery, authenticated in 1909.

So says Martin Kemp, “because it’s very soft. Above his left eye—on the right as we look at it—there are some of these marks that he made with the heel of his hand to soften the flesh, and the face is very softly painted, which is characteristic of Leonardo after 1500. And what very much connects these later Leonardo works is a sense of psychological movement, but also of mystery, of something not quite known. He draws you in but he doesn’t provide you with the answers. Most Salvator Mundis are pretty straightforward…. [But] it has that uncanny strangeness that the later Leonardo paintings manifest. I’m now thinking that it is closer to the late St. John in the Louvre than it is to the Last Supper or even the Mona Lisa.”