Art World

What Makes Someone Attack a Work of Art? Here Are 9 of the Most Audacious Acts of Art Vandalism—and What Inspired Them

Conservators, here is your trigger warning.

Conservators, here is your trigger warning.

Caroline Goldstein &

Katie White

What could possibly motivate someone to try and destroy a work of art? One might imagine that art vandals must be suffering from some form of mental instability, but in many cases works are targeted for a reason, often political, and the aesthetic aggressors aim to get their cause in the headlines by trashing a cultural treasure. (They might succeed with the latter, but we don’t yet know of any acts of art vandalism that have changed public policy.)

Here, we’ve outlined nine of the most egregious art attacks and rated them on a scale of one to five, taking into account the severity of the attack, the likelihood of successful restoration, and the perpetrator’s audacity.

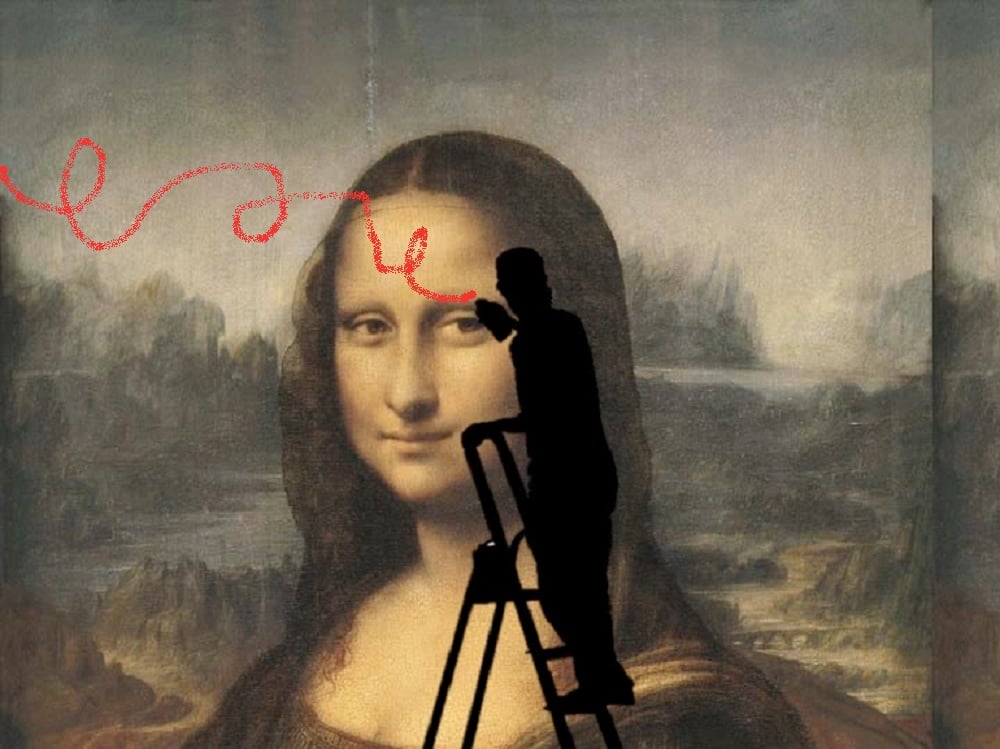

Barnett Newman, Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III (1967-68). Courtesy of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

When and Where: 1986 and 1997; the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam

Whodunit? A disgruntled 31-year-old painter named Gerard Jan van Bladeren

What and Why? The story of this painting’s multiple attacks has been so widely publicized it has spawned both a documentary, titled The End of Fear, and an episode of Roman Mars’s podcast “99 percent Invisible.” The painting itself shocked audiences when it first debuted at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam—the massive size (almost 18-feet wide and eight-feet tall) was compounded by the fact that the seemingly endless red canvas is interrupted by just two lines of colors, blue and yellow, that Newman called “zips.” The museum received letters describing visitors’ disgust and dismay that the institution would deign to show such a work, which in their opinions fell firmly into the category of “my kid could do that.”

The painting was the pièce de résistance in a show in 1986 that purported to pose questions about what, in fact, does constitute art. One man in attendance, Gerard Jan van Bladeren, was adamant that this painting did not. He stormed into the museum with a box cutter and ravaged the canvas. He was sentenced to five months in prison, but some in the community agreed with him, with one writing to the museum that “this so-called vandal should be made the director of modern museums.”

Aftermath and Legacy: Conservator Daniel Goldreyer, who had worked with Newman during his life, spent four years restoring the canvas—but he actually ruined it by painting over the entire thing with house paint.

In 1997, van Bladeren returned to the museum and when he couldn’t find Red, Yellow and Blue III, he turned to the closest Newman he could find, Cathedra, and slashed it with a small blade. The museum’s press office said van Bladeren didn’t like “abstract and realist art,” but in interviews with Dutch radio, he claimed that he was just returning to finish the job he had started 11 years earlier.

Vandalism Rating: ????? This painting has suffered enough.

The bombing victim: Rodin’s Le Penseur at the Cleveland Museum of Art.

When & Where: 1970, outside of the Cleveland Museum of Art

Whodunit? No one was ever arrested for the crime, but there were rumors that it was the work of the radical activist group Weather Underground.

What and Why? In the early morning hours of March 24, 1970, an explosion shook the large cast of Rodin’s most famous sculpture, knocking off the lower legs and damaging the statue’s base with the force of what authorities imagined to be three sticks of dynamite.

Though no one was injured in the blast, the brazen act of violence brought the community, like the sculpture, to its knees. If Weather Underground is to blame—and we’re just guessing here—then perhaps the radicalized group of students protesting the war in Vietnam targeted the work as a symbol of the elitism of those in power.

Legacy and Aftermath? Officials at the museum considered a few options after the bombing, but since it was damaged to such an extent, any alterations would have compromised the artist’s original intent. In the end, the museum opted to keep what was left of the work on display without repairs—ensuring that anyone who visited would know the sad history of the pensive figure.

Vandalism Rating: ?????

People look at the graffiti on Anish Kapoor’s Dirty Corner in Versailles. Courtesy of Versailles Patrick Kovarik/AFP/Getty Images.

When and Where: Once, twice, maybe three times in 2015 and 2016, but it depends on who’s counting; The lawn of Versailles

Whodunit? We don’t know, but Anish Kapoor called one of the vandalizations an “inside job”

What and Why: The cavernous sculpture, which is shaped like the mouth of a French horn, became the center of controversy for its possible anatomical associations, earning the unflattering nickname the “queen’s vagina” (Marie Antoinette’s, we guess?). Kapoor assured an incensed French public that there were a variety of interpretations, but to no avail. After cleaning up a first attack where the work was splattered with yellow paint, it was later scrawled with numerous anti-Semetic slurs (Kapoor’s mother is Jewish).

Aftermath and Legacy: Kapoor controversially insisted that the hate-filled graffiti should not be removed from the sculpture and instead serve as a reminder of intolerance and racism. But after a court case instigated by the Councillor of Versailles—against the artist’s wishes—Dirty Corner was ultimately covered in gold-leaf.

Vandalism Rating: ????

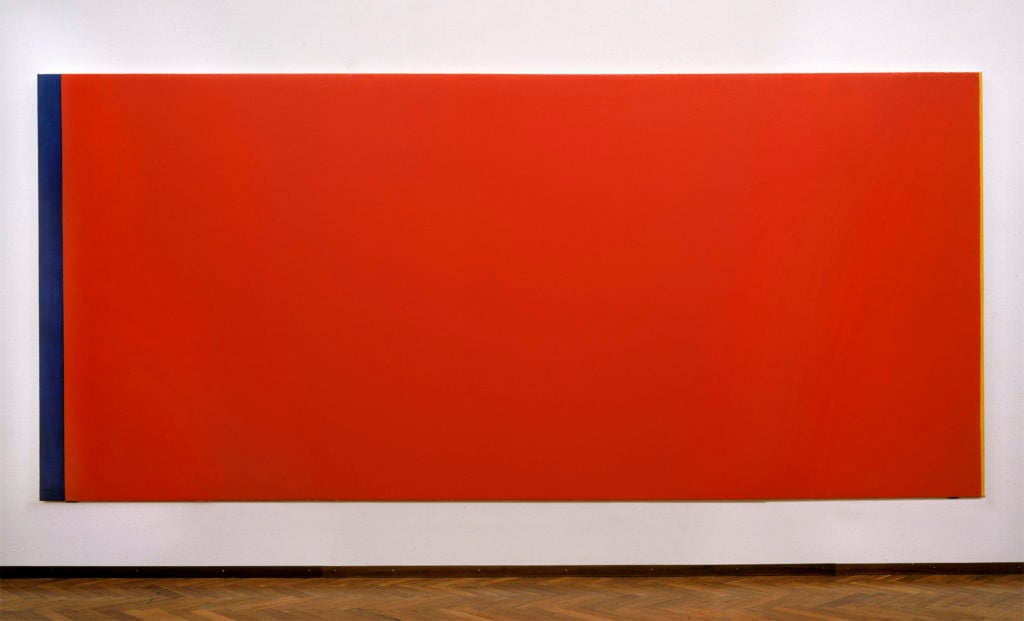

The scarred surface of Rembrandt’s The Night Watch after the second attack. Courtesy of the Dutch National Archives.

When & Where: 1911, 1975, 1990; the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam

Whodunit? An unemployed chef, a former school teacher, and an escaped psychiatric patient

What and why? Rembrandt’s colossal depiction of the Militia Company of District II under the command of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq is by all accounts an exceptional work of Dutch Golden Age painting that defies earlier, more boring compositions. Rembrandt was able to capture the feeling of excitement within the company using dramatic light and shadow, and its grand scale makes it an imposing figure in the country’s history.

Alas, with great prominence comes misguided attention, and this painting has become the repository of aggression for many disgruntled museum goers. In 1911, an unemployed Navy chef attacked the painting with a knife, but ultimately failed to pierce the thick varnish. (Perhaps, as artnet’s Tim Schneider posited, his lackluster cutting abilities factored into his joblessness.)

The second attack came on September 14, 1975, when former schoolteacher William de Rijk walked up and began slashing at the work before being overpowered by guards. Why, you ask? The man shouted that he “did it for the Lord.” And he was especially angry because he had attempted to visit the museum the night before, but arrived after closing. De Rijk was committed to a psychiatric institution, where he died by suicide just one year later. His was the most effective attack on the Rembrandt, resulting in a six-month restoration process that could not undo the deep gashes in the canvas.

The last (and hopefully, final) incident to befall The Night Watch was in 1990, when an escaped mental patient concealed sulfuric acid in a spray bottle and aimed it at the painting. Luckily, guards were able to quickly douse the work in water and the acid did not damage any paint below the varnish.

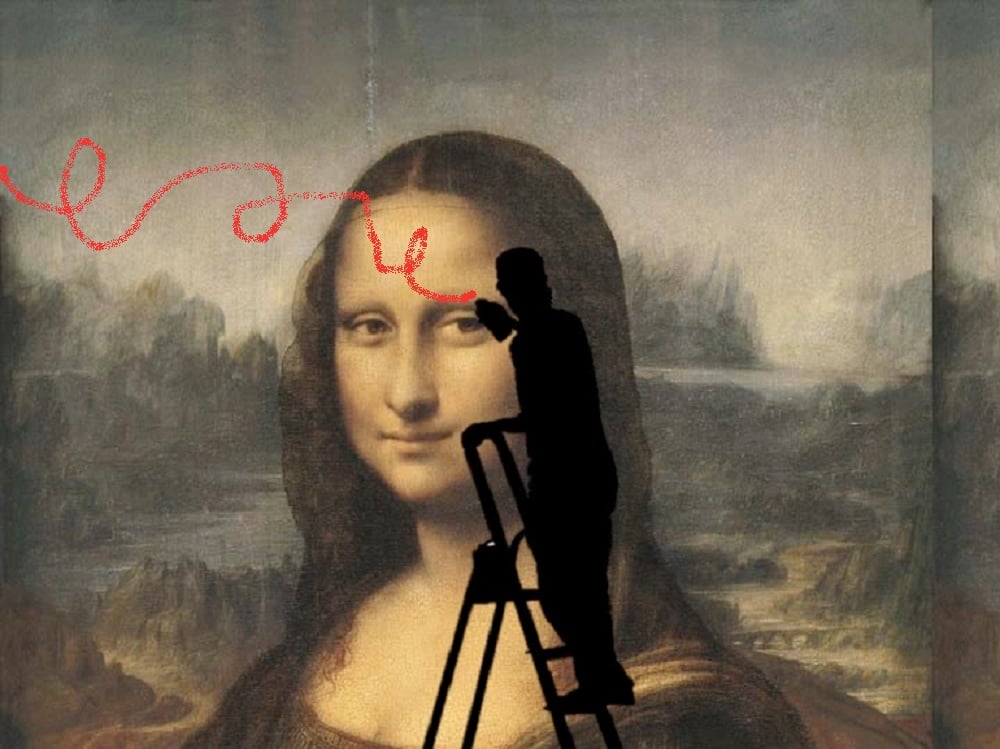

Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa. Courtesy of the Louvre.

When and Where: Twice in 1956, 1974, 2009; The Louvre and the Tokyo National Museum

Whodunit? A homeless man, a vandal, and a Russian émigré

What and Why? Her enigmatic smile and knowing eyes have beguiled adoring viewers for centuries, but the Mona Lisa has been on the receiving end of her fair share of hatred as well. The first attack came in the winter of 1956 when a homeless man named Hugo Unzaga Villega hurled a rock at the masterpiece. Why? He wanted to go to prison for the warm bed. Meanwhile, a few months prior, a vandal had tossed acid at the iconic visage while the painting was on view in a museum in Montauban, France. Eighteen years later, in 1974, a disabled woman doused the painting in red spray paint when it was on loan to the Tokyo National Museum, purportedly because she disagreed with the museum’s accessibility policies. The painting’s most recent assault came at the Louvre in 2009, when a Russian woman, apparently fuming over having been denied French nationality, flung a coffee mug at the serenely unflinching Mona Lisa.

Aftermath & Legacy: The addition of a case of bulletproof glass shielded the painting from the 1974 and 2009 attacks. And in part due to its theft in 1911 (which launched her to international super-stardom) Mona Lisa reigns unperturbed by would-be destroyers as the world’s most famous artwork.

Vandalism Rating: ???

Michelangelo’s Pietà (ca. 1488-89) in St. Peter’s Basilica. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

When and Where: Pentecost Sunday, May 21, 1972; The Vatican

Whodunit? Laszlo Toth, a Hungarian-born Australian geologist

What and Why? Toth was 33 years old at the time of the incident—the same age as Jesus at the time of his death. According to bystanders, the unwell geologist shouted “I am Jesus Christ—risen from the dead“ before leaning over the protective railing and striking the sculpture of the Virgin Mary and figure of Christ with a dozen blows of a hammer. The damage was swift and severe. The tip of Virgin’s nose was shattered into three parts. Her left arm was snapped off and she suffered damage to her cheek and left eye.

Aftermath and Legacy: Toth was not criminally charged for the offense, but was declared “socially dangerous” and hospitalized in Italy for two years before being deported to Australia. After some discussion, the sculpture was restored in a grueling 10-year process. But it was not without a silver lining: During the restoration, Michelangelo’s hidden signature was discovered. Today, the work is shown behind bulletproof glass.

Vandalism Ranking: ??

Diego Velázquez, Rokeby Venus (1649), the victim of a suffragette attack. Courtesy of Wikimedia.

When and Where: 1914; The National Gallery of Art in London

Whodunit? A Canadian woman named Mary Richardson, who was active in Emmeline Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union, walked into London’s museum with a concealed meat cleaver. She attacked the canvas, successfully slashing the exposed backside of the Venus.

What and Why? The attack was meant to draw attention to the violent arrest of the suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst, leader of the Women’s Social and Political Union, which had taken place the previous day. Richardson, a student of art, had wrestled with her choice, but ultimately felt that targeting this representation of female beauty was necessary and that any outrage felt about the destruction of the representation of a woman should be outweighed by the violence against a living one. “You can get another picture, but you cannot get a life,” she said.

Aftermath and Legacy: The painting was successfully restored and Richardson was sentenced to a (maximum) six-month imprisonment.

Vandalism Ranking: ?

A guard at the Museum of Modern Art stands watch over Picasso’s Guernica after it was restored. Photo by Allan Tannenbaum/Getty Images.

When & Where: 1974; the Museum of Modern Art in New York

Whodunit? Art dealer and collector Tony Shafrazi

What and Why? Before he became a world-class art collector, Tony Shafrazi was a gimlet-eyed artist with dreams of changing the world. On the afternoon of April 30, he ran into the Museum of Modern Art wielding a canister of red spray paint and scrawled the words “KILL LIES ALL” across the Picasso masterpiece in broad daylight, to the astonishment of visitors and museum guards. In his fervor, he shouted “I’m an artist” to stunned onlookers and then implored the group to “call the curator!”

As luck would have it, a conservator from the Brooklyn Museum had been dining in the museum’s restaurant and was quickly dispatched from her niçoise salad to assist.

Aftermath & Legacy: In just under an hour, the team was able to remove the paint. A layer of varnish had “acted as an invisible shield,” meaning that conservators were able to erase Shafrazi’s frenzied, foot-sized lettering swiftly. Shafrazi was arrested on charges of criminal mischief, but still managed to become a successful art collector and gallery owner in New York.

Vandalism Ranking: ?

Installation view of Ai Weiwei’s Colored Vases (2006). Courtesy of Cathy Carver, Perez Art Museum.

When and Where: Pérez Art Museum in Miami, February 2014

Whodunit? Maximo Caminero, 51, a local artist and, according to the Miami New Times, a pretty well-known one at that.

What and Why? A spokesperson from the recently inaugurated museum said that 51-year-old Caminero strode into the gallery and picked up one of the many color-dipped vases by Ai Weiwei (worth about $1 million, according to the museum) and, when a guard asked him to put it back, Caminero threw the vase to the ground, shattering it.

Caminero told the New Times that he “did it for all the local artists in Miami that have never been shown in museums here.” He added that the museums

Aftermath and Legacy: Caminero pled guilty to criminal mischief and paid insurers $10,000 in restitution. Surprisingly, many people in the community praised his deed, drawing parallels between Ai’s political troubles in China and those Caminero experienced as a native of the Dominican Republic. Ai himself wasn’t pleased by the vandalism, but said “I’m OK with it, if a work is destroyed,” he says. “A work is a work. It’s a physical thing. What can you do? It’s already over.”

Vandalism Ranking: ?