Art World

A New Show Explores Designer Kenzo Takada’s Fashion and Art

By embracing his Japanese roots, the designer Kenzo Takada took the Paris fashion world by storm with his colorful, exuberant vision .

At the end of 1964, a 25-year-old man from Japan stood on the deck of a massive ocean liner. The winter was cold, and he was holding a one-way ticket. He had traveled from Tokyo through Hong Kong, Saigon, and Mumbai, with his final destination being Paris. Finally, in early 1965, he set foot on Parisian soil. Who would have thought that this young man, who initially disliked Paris for its gloomy and cold weather, would eventually make such a significant impact on this city and the world?

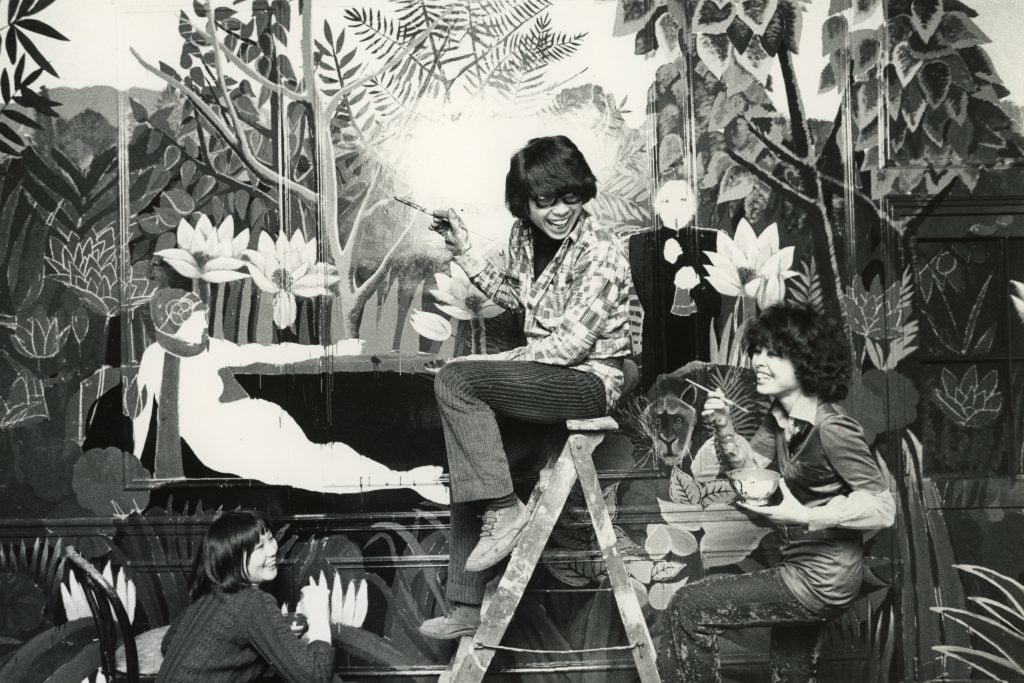

Five years later, in 1970, Kenzo Takada opened a fashion store named JUNGLE JAP in Galerie Vivienne in the 2nd arrondissement. It would later be rechristened Kenzo, and as they say, the rest is history.

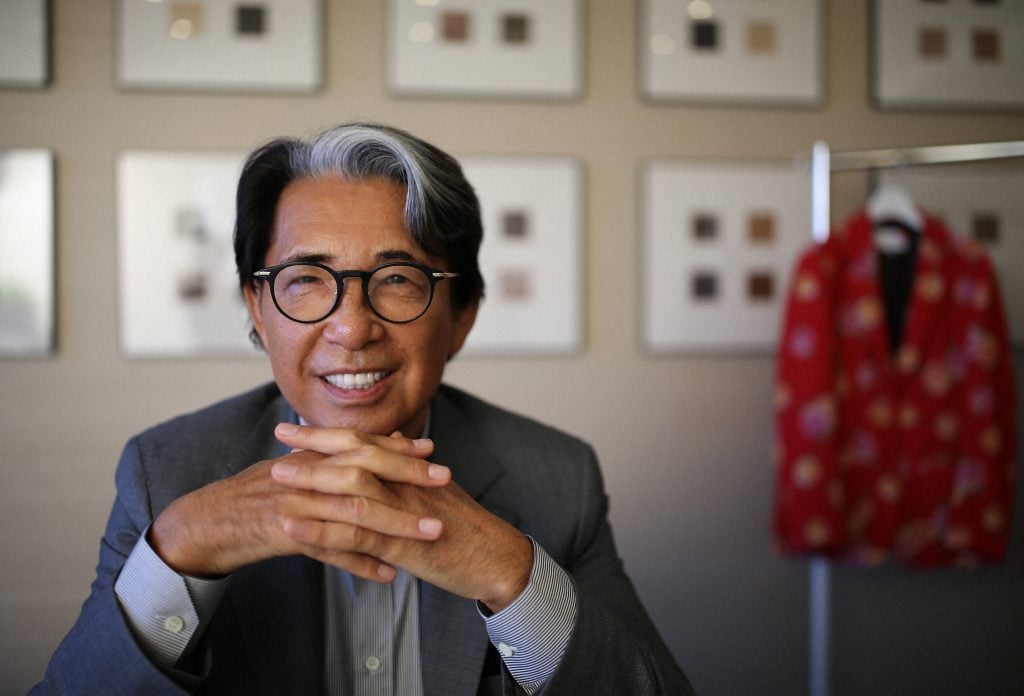

Takada died in 2020 at the age of 81. He left behind a legacy of immense creative genius for the world, especially for his homeland, Japan. Now, his story is being told through the exhibition “Takada Kenzo Chasing Dreams” at the Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery in Japan. The show unfurls the pioneering designer’s personal narrative showcases his genius creative works.

An installation view of “Takada Kenzo: Chasing Dreams.” Photo: Takahashi Kenji

Today, we are saturated with fashion exhibitions. How can the story of such a heavyweight fashion designer stand out? “This is not an exhibition about the brand,” said Fukushima Sunao, the curator. “It is about Takada’s personal life story, not about the brand.” Hence, the exhibition delves into Takada’s post-Kenzo art projects (LVMH acquired Kenzo in 1993 and he retired in 1999). However, most of the exhibition emphasizes Takada‘s most prolific creative periods in the 70s and 80s. “Kenzo showcased the best of globalization and cultural exchange. The Japanese economy was also flourishing during that era, experiencing its golden age.” Fukushima hopes that the youthful Takada portrayed in the exhibition will convey a sense of passion and courage to Japanese youth, especially those interested in fashion.

Takada Kenzo, courtesy of Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery.

Why hold an exhibition about Takada Kenzo now? “He was certainly the first one who went to Europe and started establishing the ground that is Europe-based,” Fukushima said. “So it (Kenzo) wasn’t considered a Japanese brand. It was a European brand made by a Japanese designer.”

The duality of culture runs throughout Takada’s works and life. His works never deliberately detached from traditional Japanese culture; instead, he used a lot of characteristic fabrics produced in Japan and drew inspiration from the straight cuts of kimonos.

Kenzo, 1971-1972 A/W ©︎S0-EN, 1971 September. Photo: Masubuchi Tatsuo

When Takada initially went to Paris, he was not as aware of the unique value of Japanese culture as he became later. “When he went to Paris, his motivation was to become a European fashion designer, driven by a desire to learn from the ‘better’ Europe,” Fukushima said. “But being regarded as Japanese in European society made him more aware of his Japanese identity.”

In one of the main galleries, visitors can better appreciate Takada’s creative explosion of his peak in the 70s and 80s. In 1968, four years after Takada went to Paris, the May Revolution occurred, triggering a shift in societal norms, and values. Consequently, fashion also reached a major turning point. Haute couture began to be replaced by ready-to-wear. Takada founded his brand in 1970 and launched his first collection, Spring & Summer 1970, briefly returning to Japan to search for fabrics and textiles.

The founding of the brand coincided with social changes, and echoed in Takada’s aim to liberate the body. A 1976 dress in the gallery, made with Japanese fabric and featuring iconic kimono lines, hides Takada’s anti-couture message—not to make a select few look good, but to allow everyone to be free and become who they are.

An installation view of “Takada Kenzo: Chasing Dreams.” Photo: Takahashi Kenji

In later designs, he actively incorporated playfulness. For instance, a 1989 wool dress, with a model designed by Kenzo himself, had movable joints like some dolls. He also sought inspiration across Europe, such as a lace dress inspired by priests and a coat created in 1978, derived from the contours and materials of European military uniforms, with authoritative badges replaced by soft vine and floral embroidery.

Later, he actively integrated many non-European elements into his designs. Takada always had a researcher-like interest in traditional clothing from around the world. Early in his career, he realized that square fabrics and straight cuts were common in traditional clothing across various cultures. This technique was well-suited to the diverse and new values demanded by fashion in the 70s. In the 70s, Kenzo incorporated folk themes from different countries and regions into a major trend.

Kenzo’s ribbon dress. Photo: Cathy Fan

There is an overwhelmingly beautiful, multi-colored dress made from ribbons collected by Takada over twenty years. This wedding dress, the robe de mariée, was the highlight of the 1982 show and remains a standout piece in this exhibition. It was worn by leading Japanese model Yamaguchi Sayoko in the “30ans” show held in 1999.

However, displaying the ribbon dress was not easy. Fukushima revealed that the process began with locating the dress, as she had no idea where it was. After contacting LVMH, it was found that the dress was too damaged to be easily transported out of France. Fukushima expressed her passion for showcasing this piece in the exhibition. After three months of restoration, the dress finally arrived in Japan. The high demand for Kenzo’s works also meant that many pieces remained in Europe.

Kenzo’s “ribbon dress”, 1982-1983 AW Dress (detail) ©Kazuko Masui

“I believe that during the period when his works and clothing were in high demand, many people lived in Europe. I think there are far more people in Europe who own these clothes than in Japan.”

Takada didn’t stop creating post retirement. Instead, he expanded his range of activities with greater freedom. In 2004, he designed the official uniform for the Japanese national team for the Athens Olympics. In 2019, he designed the costumes for the opera Madame Butterfly, directed by Miyamoto Amon. For the Arcrea convention center (completed in February 2021) in his hometown of Himeji, Takada depicted the World Heritage-listed Himeji Castle on the stage curtain of the Main Hall and featured the motif of the peony flower in “Sunrise” in the Large Hall and “Sunset” in the Medium Hall. Takada died before the completion of these works.

An installation view of “Takada Kenzo: Chasing Dreams.” Photo: Takahashi Kenji

The largest gallery in the exhibition is a dream for any dress lover. This stunning component is loosely arranged by different regions of the world, showcasing his iconic dress designs up to his final show in 1999. The entire gallery feels like a grand global folk culture party.

“His shows were also known for their colorful, rich, and lively atmosphere,” Fukushima said. “So, I tried to incorporate this as much as possible into the exhibition. The exhibition attempts to integrate the colors and atmosphere used in his shows. For preservation purposes, the clothes cannot be strongly illuminated, but they do not lack drama. I imagine Kenzo himself would have loved this party-like exhibition. He was such an interesting person.”