Archaeology & History

A Piece of an Egyptian Goddess Figure, Found at an Iron Age Settlement in Spain, Has Stunned Archeologists

The find raises questions about how two distinct ancient cultures came into contact with one another.

The find raises questions about how two distinct ancient cultures came into contact with one another.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

Archaeologists excavating an Iron Age settlement in Spain were surprised to discover a surviving fragment of an Egyptian goddess.

Around 2,700 years ago, Cerro de San Vicente was a walled settlement situated in modern day Salamanca in north-west central Spain. It has been an archaeological site since 1990 and more recently a tourist attraction.

The found artifact was once one of many pieces that fit together to make a glazed ceramic inlay portrait of Hathor, a powerful goddess and protector of women who was also daughter of the sun god Ra and consort to Horus, the falcon-headed god.

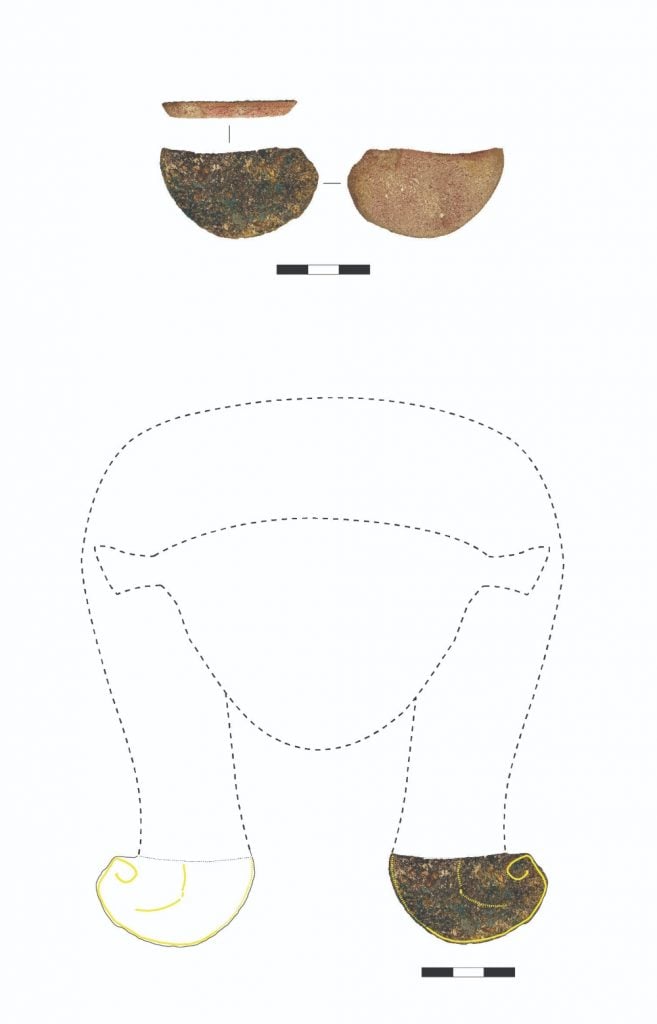

An interpretation of the inlay fragment, once part of the hair on a portrait of the Egyptian goddess Hathor. It was found in August 2022 at Cerro de San Vicente in Spain. Photo courtesy of the Unviersity of Salamanca.

Decorated with gold leaf, it shows a segment of the goddess’s trademark curly hair. This method of artistic production, not dissimilar to a jigsaw puzzle, is typical of ancient Egypt. The pieces were kept in place with glue, and the unearthed fragment is currently being examined by a lab in an attempt to determine what kind of resin was used.

It is the latest in a string of new finds at the site, including jewelry and ceramics adorned with Egyptian motifs. Another portrait of Hathor, this time a blue quartz amulet, was found by the research team in the summer of 2021. It was made in ancient Egypt and reached the Iberian Peninsula in around 1,000 B.C.

Together, these objects raise questions about the history of the region.

“It’s a very surprising site,” the archaeologist Carlos Macarro told El Paīs. “Why did the inhabitants of an Iron Age settlement have Egyptian artifacts? Did they adopt their rites? I can imagine Phoenicians entering the hilltop settlement carrying these objects, wearing their brightly colored clothing. What would these two peoples have made of each other? It’s very exciting to think about.”

Macarro is working on the dig with fellow archaeologist Cristina Alario and in collaboration with Antonio Blanco and Juan Jesús Padilla, both professors of prehistory at the University of Salamanca.