Art & Exhibitions

A Wake-up Call for the Whitney Biennial 2014

The Yams Collective's withdrawal is an opportunity to rethink the whole event.

The Yams Collective's withdrawal is an opportunity to rethink the whole event.

Ben Davis

I’m hoping that the announcement that The Yams, a group of African-American artists, is pulling out of the Whitney Biennial—go read Mostafa Heddaya’s story (and all the updates, which answered a lot of questions I had about the original)—can spark an actual conversation. And not in the way that art normally “engages in dialogue” and “questions issues of representation,” but in the way that actually changes something. I’m hoping that it can stimulate a discussion about what the Biennial actually is and who it is for.

Fortunately for me, I haven’t seen the show (I’m only just back in town, and I thought the Whitney Biennial’s moment was over), so I can’t comment on the very tough question at the heart of this story. The Yams object to being shown alongside the work of Joe Scanlan, a white male artist who has engaged in a long-running performance project wherein he hires African-American women to play a fictional artist (who herself does work that plays with identity, performing Richard Pryor stand-up routines, for instance). I tend to think that such a gesture is not inherently evil; I assumed that it was precisely about exploring how one imagines and relates to and constructs experiences that are very different than one’s own. But I just don’t know. I know some consider it a form of racial drag, and the specifics to be tone deaf. I know from Andrew Russeth’s long profile of Scanlan that the project is meant to provoke, has at times made audiences angry, and that curator Michelle Grabner knew she was courting controversy.

I also know that the New York Times dedicated an entire feature to The Yams’s inclusion in the 2014 Biennial, giving the show some its best press, just as now it is getting some of its worst. “I’d go to art events, and I’d be the only black person in the room—here in New York,” collective founder Sienna Shields told the Times, explaining the origins of the group. If you are a collective of artists of color who deliberately banded together as a survival strategy, it does make some sense that Scanlan’s art project seems unsettling. And again, not in the normal way that art “unsettles boundaries,” but in a way that reminds you that your own identity is being scrutinized in an unwelcome way. For Scanlan, incarnated identity is lighter than air: he literally describes looking at his own works and asking “who their author should be.” For the members of The Yams, incarnated identity is something you can’t escape, that people remind you of all the time. You can see how this is a clash that was bound to happen.

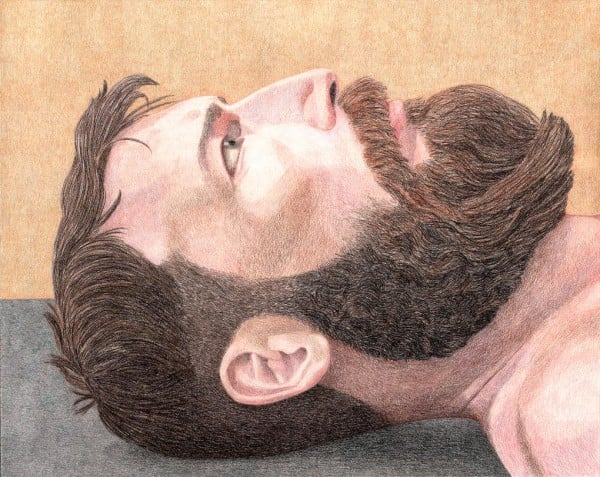

Donelle Woolford, Avatar (2007).

Collection of the artist. Photograph by Donelle Woolford.

Context actually matters. And the context in which this occurs is a Whitney Biennial that has a race problem. If people weren’t already looking at the artist list and counting the totals and seeing that they came up severely short as soon as the show was announced, then maybe the inclusion of Scanlan’s fake “Donelle Woolford” couldn’t be contextualized as a bait-and-switch attempt to occlude the situation of real African-American women artists (Woolford, not Scanlan, is listed in the show’s roster). But if “ifs and buts” were candies and nuts, then every day would be Christmas. You don’t “explore identity” in some nebulous blank space; you explore it in actual space, which in this case is already charged with tension over identity. Scanlan’s work might be very sensitively done and still seem a slap in the face in this context.

The Biennial’s own statement about The Yams exodus (“The Whitney Biennial has always been a site for debate—no matter how contentious or difficult—of the most important issues confronting our culture”) is boilerplate PR crisis-speak. If by “a site for debate” the museum means that people generally complain about the Whitney Biennial, then it is correct. The Biennial is essential viewing, but what it always provokes is criticism and eye-rolling. This is in some ways not the curators’ fault. Its implicit mission, to provide a representative slice of the best of the present—the current survey actually claimed at the front that it was “one of the broadest and most diverse takes on art in the United States that the Whitney has offered in many years”—practically begs observers to look at it and say, “This is not representative. This is not the best.” Claim to speak for the universal and the particularities of your taste are bound to be questioned.

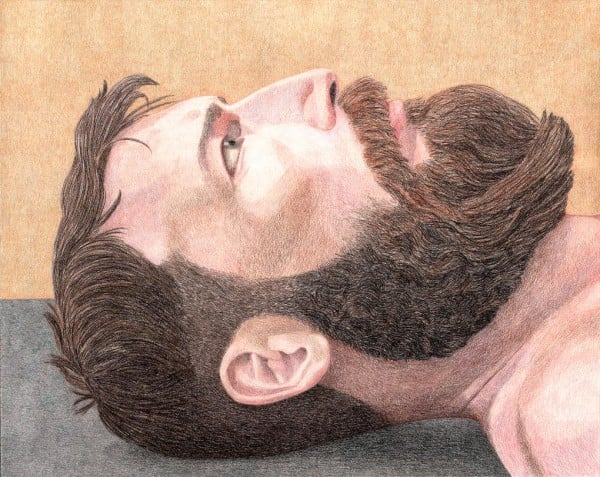

HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN?, Good Stock on the Dimension Floor: An Opera (2014).

Collection of the artists. © HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN?.

A lack of diversity infects the entire art scene. The audience for museums and galleries in the United States is 89 percent “non-Hispanic white,” according to data compiled in 2010. As Reach Advisors, which studies these things, wrote, “there are huge gulfs between museums and African American audiences and Hispanic audiences.” The art crowd is far, far, far less diverse than the population of the US in general even as that population becomes more diverse. So don’t say that the current incident is just about a few artists’ hurt feelings. No matter what you think about Scanlan and Yams Collective, this is about the most vital issue that art can confront, which is its own continued relevance.

After the Whitney Biennial’s initial list came out last year, I did some research about diversity (or lack of diversity) in art, to try to figure out what is to be done. Among others, I interviewed Elizabeth Merritt, head of the Center for the Future of Museums in Washington, DC, asking her what institutions have been doing to try to make themselves more relevant to non-white audiences. “What museums are finding is that it isn’t enough to make it a one-off,” she told me. “You can’t just do a Day of the Dead celebration and say, ‘There, we serve the Hispanic community.’ The message is that it has to be deep and embedded.” Similarly, some representation in a Biennial that doesn’t feel really representative is bound to raise tensions.

Installation view of the 2014 Whitney Biennial.

Photo: Benjamin Sutton

If I were the Whitney Museum, instead of taking the present incident as something to be perception-managed out of existence, I would take it as an opportunity to rethink how its signature event might actually be more vital. The mainstream commercially driven art market does not naturally generate diversity, because commercial pressures tend to amplify existing advantages and disadvantages: It’s all about whom you know, and whether or not you sell.

But that’s exactly where a supposedly non-commercial institution like the Whitney, and a supposedly scholarly initiative like the Biennial, should be relevant. Instead of representing the best of the official scene, it should aspire specifically to represent the best of what doesn’t get represented within that scene. Diversity wouldn’t be an ass-covering afterthought in such a show, but something welded into its fabric in a “deep and embedded” way. This might take some extra effort in terms of seeking things out. But as Shields said in that Times profiles, “There’s all this vast talent. I thought of all the great people I’d known in my years in New York and I thought, ‘Let’s exert ourselves!’” What a clear curatorial brief that would be! What a clear reason to be interested as a critic! What an opportunity to reach an audience beyond the usual art audience! Maybe the Yams Collective could curate the next Whitney Biennial.