During the press conference for the soon-to-open Academy Museum of Moving Pictures in Los Angeles, the Pritzker Prize-winning architect Renzo Piano had one request. “Please,” he asked the assembled crowd of journalists, “don’t call it the ‘Death Star.'”

While the museum has been under construction over the past six years, that less-than-flattering nickname stuck to his design, a glass-and-concrete 130-foot-tall sphere that now makes up one half of the institution. Piano would prefer you use the term “Soap Bubble,” but would also settle for “Zeppelin,” “Spaceship,” or “Flying Vessel.”

Whatever you call it, the movie capital’s very first museum of cinema opens on September 30, a full nine years after initially unveiling its architectural plans.

Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. Photo: Iwan Baan/©Iwan Baan Studios, courtesy of Academy Museum Foundation

Piano’s newly completed—O.K., fine—“Soap Bubble” features a plush 1,000-seat theater in red-carpet red, plus an open-air terrace beneath an enormous glass dome. Two glass-enclosed bridges connect the sphere to a rectangular 1939 former department store, which Piano’s team refurbished to include five floors of facilities named after familiar patrons, including the David Geffen Theater, the Spielberg Family Gallery, the Netflix Lounge, and the Dolby Family Terrace.

Culling from the 13 million-item archive of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, plus its own growing collection of movie ephemera, the new 300,000-square-foot, $482 million museum frames cinema not only as an art form, but more broadly as a reflection of the politics, technologies, and cultural values of its time. Opening after years of setbacks, delays, and changes in leadership, the museum also has a lot to tell us about the present.

A Different Kind of Film History

The notion of a museum devoted to cinema first emerged during an Academy board meeting in 1929, two years after the organization’s founding. Almost a century later, concrete architectural plans materialized in 2012, and the project broke ground in 2015. From there, beyond the usual construction delays and ballooning budget, the museum faced a major setback in the sudden departure of director Kerry Brougher in August 2019.

Some would argue the change was for the better. Brougher’s replacement, Bill Kramer, brought a fresh sense of self-awareness to the museum at a moment when audiences have come to demand cultural institutions take a more critical look at themselves and the art they promote.

Installation view, “Significant Movies and Moviemakers: Real Women Have Curves (2002), “Stories of Cinema 2” Photo: Joshua White, JW Pictures/ Academy Museum Foundation.

The mandate to work closely with the museum’s Inclusion Advisory Committee “really strengthened when Bill Kramer came on board,” curator Dara Jaffe told Artnet News. “The scrutiny of representation is part of the larger culture at the moment, and we’re glad to be opening now because we can be a part of that.”

Under Kramer, the museum developed a core exhibition entitled “Stories of Cinema.” Jacqueline Stewart, who was named chief artistic and programming officer last year, noted that the “plural” was intentional. While Brougher was working on a more linear history of cinema, the new hires expanded that vision. “Our premise is that there are multiple histories of film, some of them only now coming to life,” Stewart explained.

After deploying more than a dozen task forces, the museum scrapped Brougher’s permanent core exhibition in favor of one that would change over time, making space for a canon to evolve rather than fossilize.

Academy Awards History Gallery, “Stories of Cinema 2.” Photo: Joshua White, JWPictures/ Academy Museum Foundation.

This approach strikes a balance between the critical and celebratory, aspiring beyond cancellation to a degree of reconciliation. Problematic histories are woven into the narrative rather than siloed in separate rooms. The Academy Awards History gallery, for example, notes that the first award for makeup in 1965 went to William Tuttle for 7 Faces of Dr. Lao “despite the film’s overt use of yellowface, the racist practice of Asian characters.” Elsewhere, a MaxFactor foundation in the shade Minstrel Black is on display.

The Western is presented as the earliest film genre alongside a brief documentary of Indigenous activists calling for more humane representation in film. Galleries devoted to the works of Black directors Spike Lee and Oscar Micheaux showcase their accolades while capturing their response to the racism they experienced throughout their careers.

The displays portray the world-building art of cinema as a collaborative process, with dedicated galleries to the casting director, makeup artist, set designer, and more. Stories are told through objects, including Dorothy’s two dresses from the Wizard of Oz (in a stroke of low-tech ingenuity, the director faked the transition between black-and-white reality and technicolor Oz by putting Judy Garland’s body double in a sepia-dyed dress).

The Academy’s archives, along with the participation of its members, work together in ways that feel very intimate. In one clip, veteran casting director Kimberly Hardin recounts her long history of collaboration with the late film director John Singleton, providing archival footage of a young Taraji P. Henson and Tyrese in a heated audition for Singleton’s 2001 movie Baby Boy.

Ruby slippers worn by Judy Garland in The Wizard of Oz (1936) in “The Art of Moviemaking Gallery, Stories of Cinema 2.” Photo: Joshua White, JWPictures/ Academy Museum Foundation.

“As a part of the Academy, we have incredible access to the viewpoint of the filmmakers themselves,” Jaffe said. “Getting to actually see their faces and see them talk was important to us.”

Consulting with living filmmakers also lends the project a sense of immediacy and authenticity. Icelandic composer Hildur Guðnadóttir created a haunting new score to inaugurate the dedicated Composer gallery under the light of a floating red orb. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the sound quality is amazing throughout the museum.

Toward a Modern Museum

Given the universal nature of movie-going, these wide-ranging presentations aim to appeal to a large swath of audiences. “It’s classical object display, as well as an interactive experience,” said Doris Berger, the museum’s director of curatorial affairs.

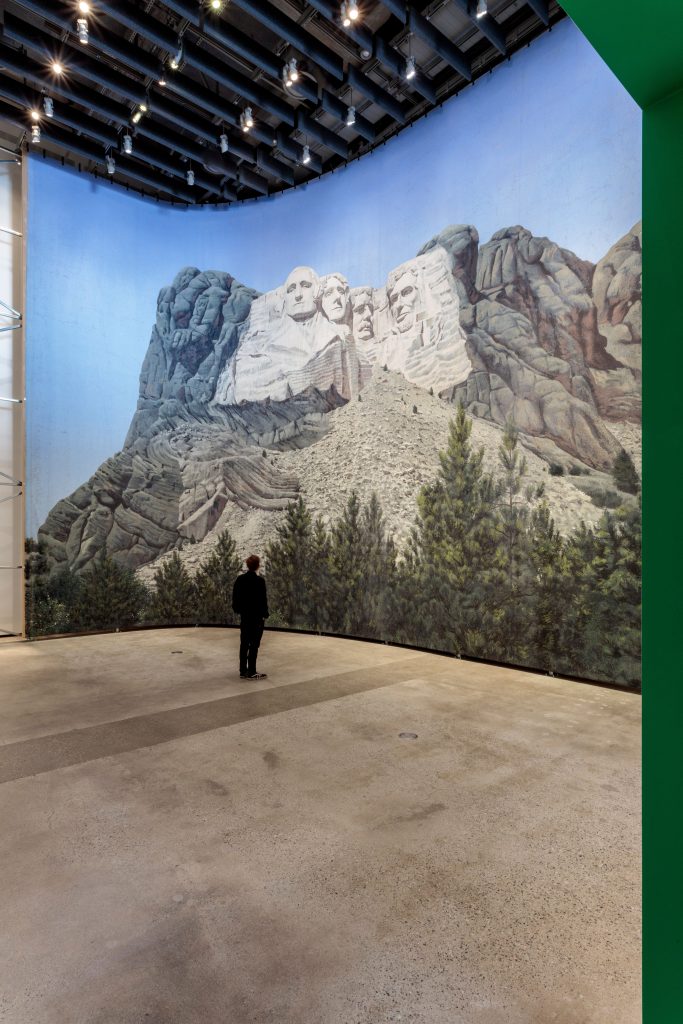

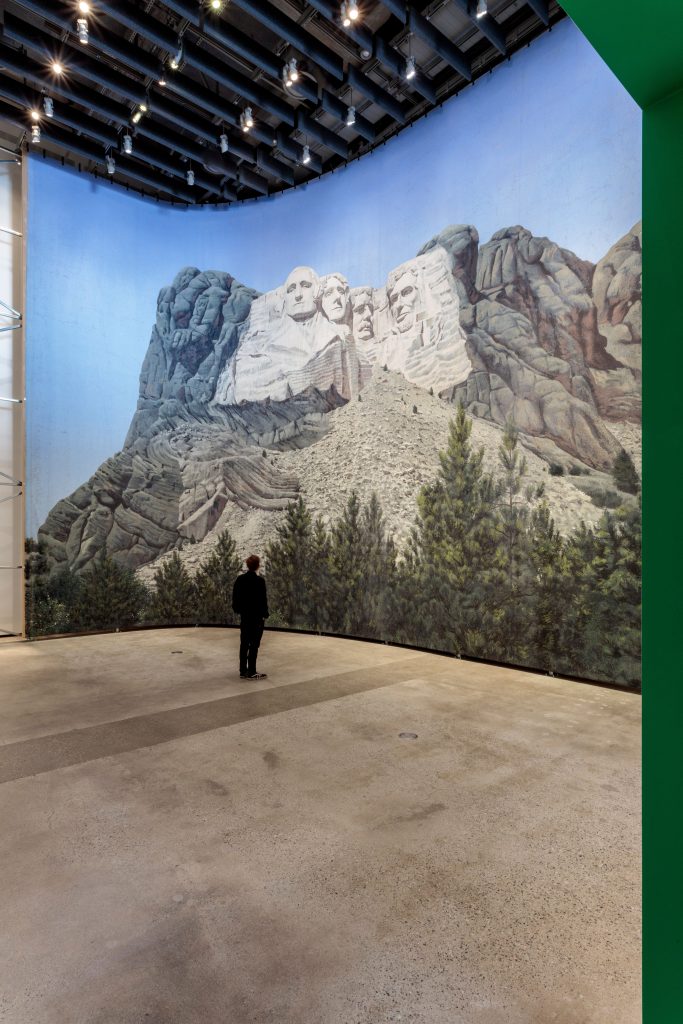

Backdrop: An Invisible Art, Hurd Gallery, Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. Photo: Joshua White.

No new museum would be complete without immersive experiences, and the Academy Museum delivers with two augmented reality options: a hilly patch of fake grass to gaze upward at an animated sky, and what it’s calling the Oscars Experience. On a stage facing a digital audience’s standing ovation, visitors can hold an actual eight-pound Academy Award and have the footage emailed to them, an appeal to our current age of main character energy.

Through it all, the Academy Museum aspires to reflect a contemporary paradigm for cultural institutions—one that honors a complex history with a sense of wonder and nostalgia while acknowledging its flaws.

“Hayao Miyazaki” at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. Photo: Joshua White, JWPictures/ Academy Museum Foundation.

At the moment, the museum has no solo exhibition on a woman director. The inaugural focus on Hayao Miyazaki and Pedro Almodóvar, a Japanese and Spanish director respectively, “is a statement of intent for our international scope,” said Berger, although certain galleries read as an homage to the Hollywood blockbuster. “Inventing Worlds & Characters” features models and costumes associated with Hollywood’s favorite sons: George Lucas, Tim Burton, Walt Disney, Stanley Kubrick. (Here it becomes clear that Piano’s building is not a Death Star at all, but the Aries lander of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.)

Back in the Academy Awards History gallery, the written timeline begins with the first award show in 1929, and ends in 2021, when Chloé Zhao became the first Asian woman and second woman ever to win the award for best director. It’s a reminder that progress is still nascent—but the new museum saves space to ensure that new stories will be told.