Law & Politics

The ACLU Is Suing Miami Beach for Censoring a Memorial Portrait of a Black Man Who Was Killed by Police

The work briefly appeared as part of an exhibition in Miami Beach last May.

The work briefly appeared as part of an exhibition in Miami Beach last May.

Sarah Cascone

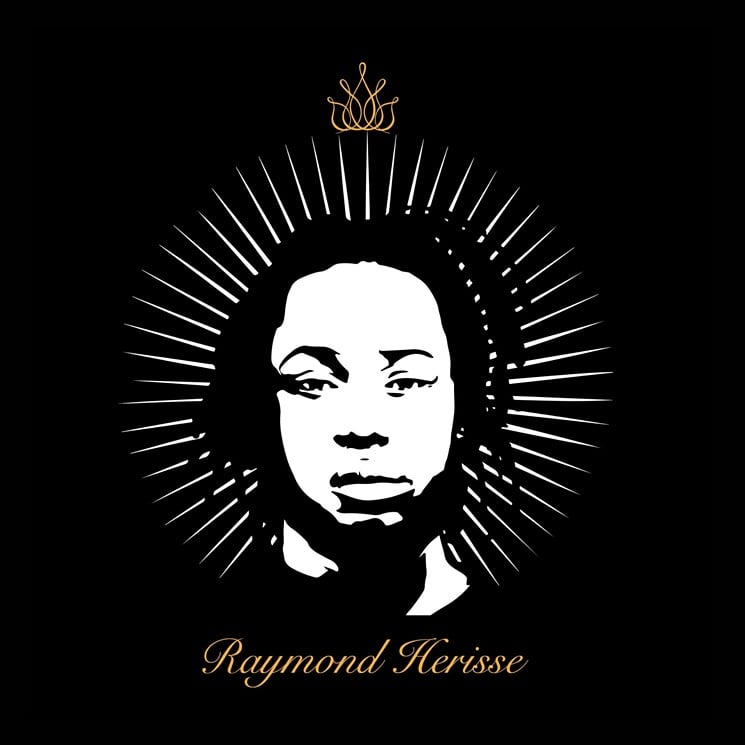

The American Civil Liberties Union is suing the city of Miami Beach for censoring a painting by artist Rodney “Rock” Jackson that depicted Raymond Herisse, a Black man who was killed by Miami Beach police in 2011.

The ACLU Florida and the ACLU Greater Miami chapters maintain that the forced removal of the artwork, commissioned by the city in 2019 for the project “ReFrame Miami Beach,” was a violation of the artist’s first amendment right to free speech. The lawsuit was filed on behalf of Jackson and curators Octavia Yearwood and Jared McGriff.

The Memorial to Raymond Herisse was among the works on view on Lincoln Road as part of the exhibition titled “I See You Too” last Memorial Day Weekend. The day after the opening, the curators received a call from the city demanding that the painting—or else the whole show—be taken down.

“I was stunned,” Jackson said at a press conference announcing the lawsuit. “Then I slowly became outraged. I could not understand how an image that was meant to memorialize someone could be offensive.”

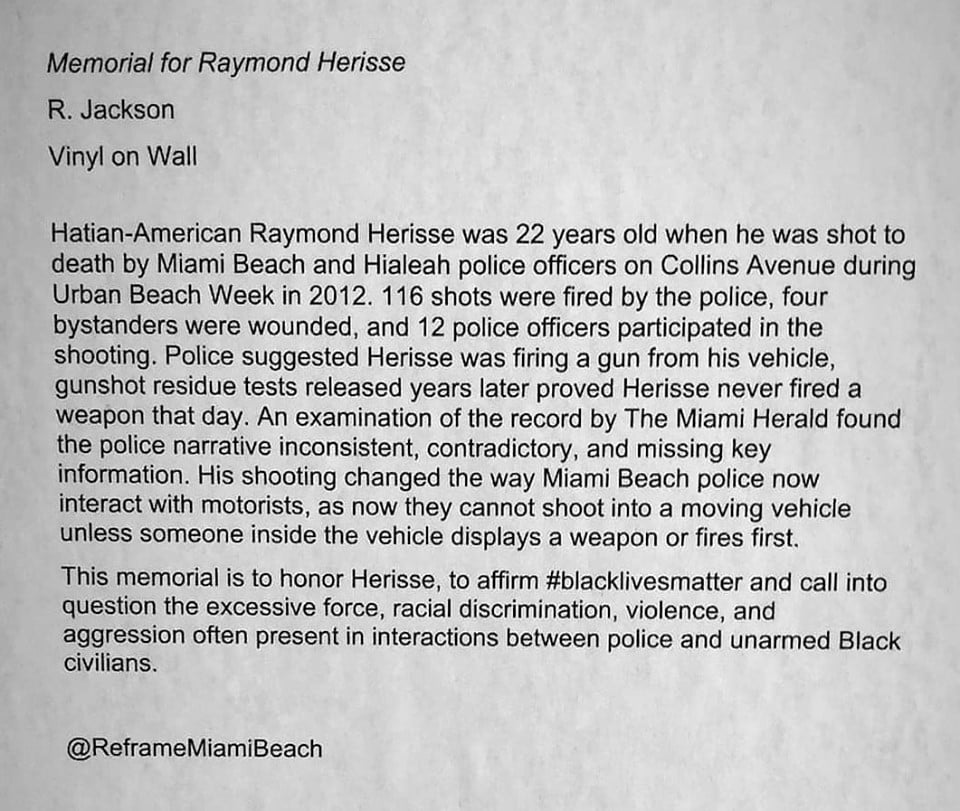

The wall text for Rodney Jackson’s Memorial to Raymond Herisse, which was removed by “ReFrame Miami Beach” at the insistence of the city of Miami Beach. Photo courtesy of the artist.

In the lawsuit, the ACLU points to a long history of racism in Miami Beach, citing the segregation of its hotels and beaches into the 1960s. Herisse died during Memorial Day weekend, known locally as Urban Beach Weekend, a celebration widely attended by young people of color.

“It’s a weekend that’s been characterized by aggressive police enforcing and racialized violence, [and is the] subject of criticism of civic groups across South Florida” said Alan Levine, a lawyer for the ACLU, at the press conference.

In the 2011 incident, police fired 116 shots into Herisse’s moving vehicle, fatally wounding the 22-year-old. The officers involved were never charged, but the city paid Herisse’s family $87,500 in a settlement, and now prohibits police from firing at moving vehicles.

A communications director for Miami Beach, Tonya Daniels, told Artnet News that the city had not yet been served the lawsuit and “therefore we cannot provide any comment on this pending litigation against the city and its officials.”

The curators of ReFrame say that their conversations with city manager Jimmy Morales led them to believe that the project was meant to encourage difficult conversations about race relations and inclusion.

“That this exhibition, and particularly the memorial to Raymond Herisse, was censored showed that the city was unwilling to collaborate with us in good faith, and their desire subordinate the ideas of Black people in the interest of hiding unfavorable facts about the police,” said McGriff in the press conference.

“The censorship in this case has to be viewed and understood in a larger context, which is a longstanding campaign to silence and delegitimize the movement against racialized police violence specifically toward young Black males,” added Matthew McElligott, a lawyer from Valiente, Carollo & McElligott representing the ACLU.

He referenced the ongoing Black Lives Matter demonstrations triggered by the Memorial Day death of George Floyd and said, “When you repeatedly prevent peaceful expression, it boils over.”

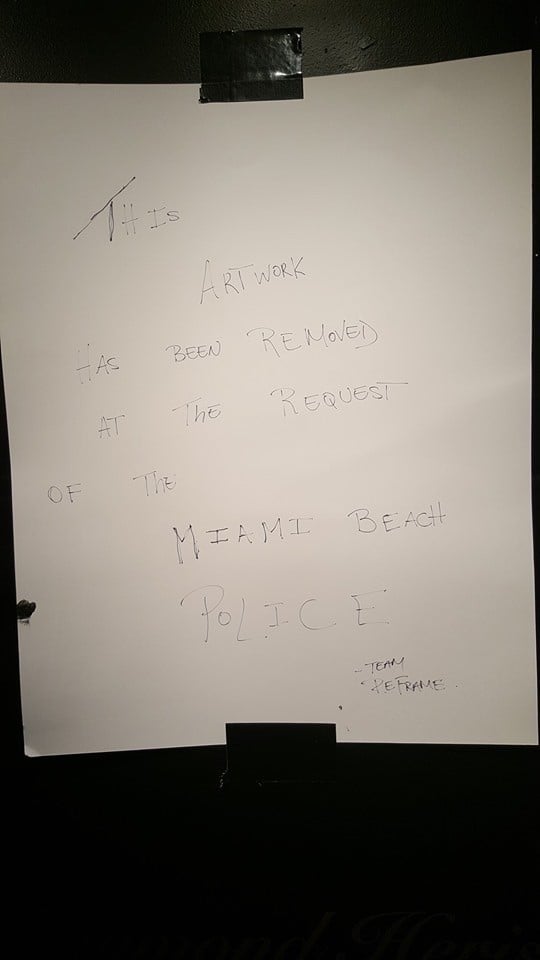

Curators of “ReFrame Miami Beach” replaced Rodney Jackson’s Memorial to Raymond Herisse with this note at the insistence of the city government. Photo courtesy of the artist.

The complaint contends that Morales and Miami Beach mayor Dan Gelber, both named as defendants in the suit, openly stated that they had removed the work because they didn’t like it, and therefore shouldn’t have to pay for it.

“The defendants will say this isn’t censorship,” said Levine. “The truth is… public money cannot be allocated based on whether or not public officials approve of somebody’s point of view.”

There are two legal precedents based on First Amendment rights cited in the complaint. In 1999, the court ruled against then New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani in his bid to evict the Brooklyn Museum over its display of Chris Ofili’s The Holy Virgin Mary, which featured nude photographs and elephant dung. Miami’s similar action against the Cuban Museum of Arts and Culture for exhibiting works by Cuban artists not deemed sufficiently anti-Castro was also shot down by the courts in 1991.

The current lawsuit asks the court to declare that the city’s insistence on the artwork’s removal was a violation of the First Amendment and wants the city stage a comparable exhibition featuring the painting. The plaintiffs are also requesting monetary damages in an amount to be determined at trial.

“This is not an isolated event. Where Black folks are policed and monitored and surveilled physically, the same thing happened in the idea space in our exhibit,” said McGriff. “The fact that Black people are exhibiting their ideas and exercising their agency is offensive to some people, and I think that’s what occurred here.”