Art World

Adam and Eve Return to Original Nude State After Botched Cover-Up Job

Is this the Renaissance-era version of "Beast Jesus"?

Is this the Renaissance-era version of "Beast Jesus"?

Eileen Kinsella

In a fascinating mash-up of art history, science, and one decidedly prudish former owner, the Guardian reports that images of Adam and Eve in a historic illuminated manuscript have been restored to their original nude state, centuries after being crudely clothed by a former owner.

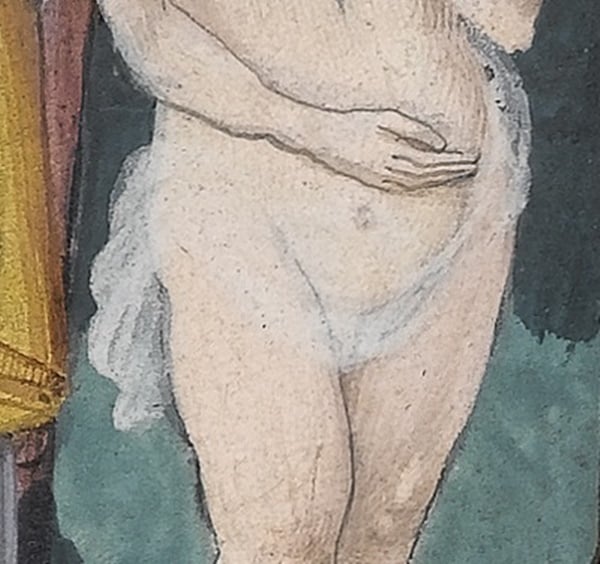

The figure of Eve covered with a wispy veil. The figure of Courtesy of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, England.

The book is currently on display at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, England—which is celebrating its bicentary this year—as part of the exhibition “Colour: The Art and Science of Illuminated Manuscripts,” which runs through December 30.

Covered figures of Adam and Eve. Courtesy of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, England.

Queen Anne of Brittany considered the original nude figures to be perfectly appropriate in 1505. She commissioned the book, The Primer of Claude of France, as a gift for her five-year-old daughter.

Later on, the person who came to own the book had them covered up by an unknown fix-up “artist”; Eve was given a “wispy veil” while Adam got “a particularly unflattering and crudely painted skirt,” writes the Guardian‘s Maev Kennedy.

The only figures in the book left untouched were of the two after the fall, when they are already covered with fig leaves.

Adam and Eve in their original naked condition following algorithmic treatment by Cambridge University’s Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics. Courtesy of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, England.

Curator Stella Panayotova told the Guardian that the museum has been aware of issue for years. “But there was nothing we could do about it. Unlike our colleagues in painting, where later overpainting is often removed, we would not touch an original page in good condition,” she said.

The Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics at the University of Cambridge had developed a program whereby they can fill in areas of missing color in paintings by scanning and filling in the gaps with surviving pigment. Panayotova asked them to try to reverse that process by stripping away paint.

The result? “It has succeeded beyond our imagination…” says Panayotoya.