What I Buy and Why

How Chair Collectors Adam Weintraub and Mishi Hosono Got Engaged With a Promissory Seat Instead of a Ring

The architects' New York loft is overflowing with designer chairs.

The architects' New York loft is overflowing with designer chairs.

Lee Carter

There’s no better way to explain the fascination that Adam Weintraub and Mishi Hosono have with chairs than to the tell the tale of their engagement. The architects behind the New York-based design firm Koko were in Rome—”in the middle of the Campo De Fiori”—when a smitten Weintraub pulled out a ring box not with an engagement ring inside, but an engagement chair—or rather, a picture of one.

Who could turn down the promise of a life built on collecting chairs? The couple has gone on to acquire quite a few, to put it mildly. Their West Village loft, where space is already at a premium, is piled high with seating by Eames, Aalto, Kuramata, Jacobsen, and a “very unusual” steel chair designed by Rei Kawakubo in the 1980s for her Comme des Garçons showroom. They fashioned a baby bassinet out of Gerrit Rietveld Zig Zag chairs when their children were young, and a few years later helped their young daughter craft an Enzo Mari chair from scratch.

Guided by a philosophy of play and learning, the architects specialize in designing children’s education spaces, recently constructing a 3,500-square-foot interdisciplinary discovery and play space at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The 81st Street Studio is an inclusive and free-of-charge place for discovery for visitors of the under-five-foot kind. They’re also committed to community participation, having led lectures and workshops for the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, the Scandinavia House, and the Japan Society.

We spoke with the couple about their very different upbringings, scavenging their first pieces, and nabbing a work by Isamu Noguchi if given the chance and a big enough coat.

Eames armchair Rocker (1950). Courtesy of Adam Weintraub and Mishi Hosono.

Congrats on being the first chair collectors featured in this column. How did that start?

Adam: Mishi and I share a passion for chairs but arrived at it from very different backgrounds. I grew up in Michigan and went to school at Cranbrook surrounded by the older Saarinen’s buildings and furniture by Eero Saarinen, Charles Eames, and Harry Bertoia. The dining hall chairs in the high school were lacquered pink and maple, not your typical institutional chairs. My childhood home was a midcentury house built by a Scandinavian woodworker, and my parents taught me about furniture from a young age.

Mishi: I grew up in an old wooden Japanese house in downtown Tokyo. Since many of the rooms had tatami mats, it was more about a lack of chairs. I am always fascinated by how Western designs are modified to fit Japanese culture. These contrasting cultures are an important part of our design practice.

Adam: I think most architects have a fascination with chair design. Some might say it is easier to design a good building than a good chair. The other interesting thing about chairs is that people can choose which chair to sit on or which to put in their homes. We often do not get a choice of which buildings we are going to enter.

Arne Jacobsen Series 7 counter stools (1955), upholstery by Kvadrat. Courtesy of Adam Weintraub and Mishi Hosono.

What was your first purchase?

Adam: Many of our first chairs were scavenged rather than purchased. I still remember spotting some Eames shell chairs in a garbage pile next to a dentist’s office on Gramercy Park. It is always exciting to “find” chairs, but there were also designs that we admired that couldn’t be rescued from dumpsters.

Mishi: Our first purchase as a couple was the Jasper Morrison 1988 Plywood chair manufactured by Vitra. This is an extraordinarily minimal chair that prioritizes design over comfort. As we often tell our clients, some chairs are for “looking at rather than sitting on.”

Jasper Morrison plywood chair (1988). Courtesy of Adam Weintraub and Mishi Hosono.

What was your most recent purchase?

Adam: The problem with collecting chairs if you live in New York is that they take up quite a lot of room. Our daughters have recently told us “no more chairs.” Fortunately, we have a small place in Tokyo, so we have an excuse to look for chairs in Japan. We recently purchased a three-legged shoemaker stool that is ideal for removing shoes in Japanese homes. It is untreated natural beech and you can see the joinery and craftsmanship.

Enzo Mari, Sedia 1-Autoprogettazione, designed in 1974, fabricated in 2013. Courtesy of Adan Weintraub and Mishi Hosono.

Tell us about a favorite item in your collection.

Adam: When our daughter was ten years old, she and I built an Enzo Mari Sedia 1-Autoprogettazione chair. This chair was designed by Mari to allow everyone to have a good chair. He published the plans and said you can make it yourself as long as you don’t sell it. The chair is assembled from wood scraps and nails. Despite its appearance, it is quite comfortable as the dimensions are very precise. But it is one of our favorites because it was made with our daughter when she was quite young. She is currently in college, and is leaning towards a career in architecture.

Loft interior with Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona chair (1929), left, Alvar Aalto’s Tank chair (1936) with Missoni upholstery, right, and an original Eames molded plywood leg splint (1943) on the wall. Courtesy of Adam Weintraub and Mishi Hosono.

We understand there’s an engagement chair in the mix. Do tell.

Mishi: Most couples look to an engagement ring as the traditional sign of commitment. Well, when Adam proposed in the middle of the Campo De Fiori in Rome he couldn’t drag a chair into the street. Instead, he had a small Spinneybeck leather sample in a ring box along with a small photo of the Barcelona chair.

Adam: Not only did she say yes to marriage, but Mishi even approved the color! The chair now sits comfortably in the middle of our 19th-century West Village loft.

Which works or designers are you hoping to add to your collection this year?

Adam: Space is a problem when you collect chairs, but we are not always practical when it comes to our collection. When Mishi turned 50, we did a survey and realized that we had at least 50 unique chairs. We always have a few in mind, but some from our wish list include: Finn Juhl’s Pelican chair (1940), Michele De Lucchi’s first chair (1983), and Shiro Kuramata’s Miss Blanche chair (1988).

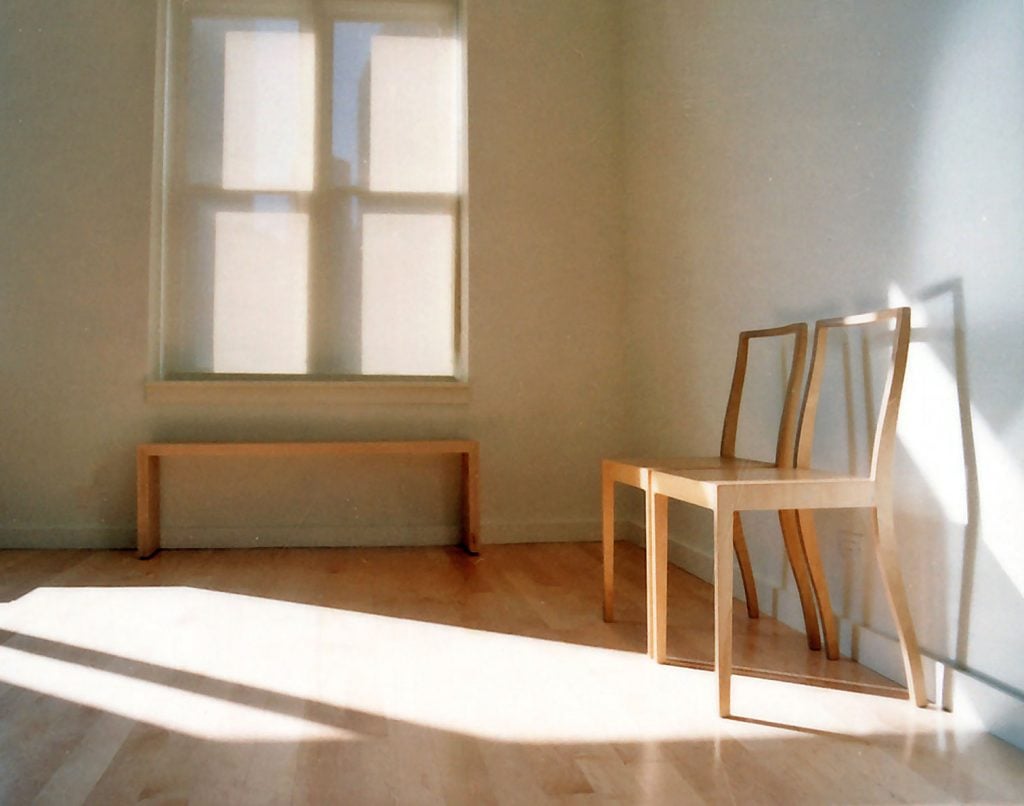

Alvar Aalto, Artek 66 chairs (1935). Courtesy of Adam Weintraub and Mishi Hosono.

What is the most valuable work that you own?

Adam: We have a very unusual chair that was designed by Rei Kawakubo in the 1980s for her Comme des Garçons showroom in Soho. We were gifted the chair by a close friend who knew how much we love chairs and how much Mishi loves Comme des Garçons. It is made of very rough galvanized steel, and captures Rei Kawakubo’s understanding of construction and materials.

What’s it like being architects for the under five-foot crowd?

Adam: Designing for children’s spaces has given us a freedom we don’t always find when designing for adults. We can approach a problem with the innocence of a child’s perspective. This does not mean our designs have to be simplified or childish, but the exact opposite.

On the one hand, children can be very critical. If they don’t like it, they will tell you. On the other hand, when they do like it…they really like it. Our goal is to create spaces where both children and adults can discover a new world, as we did with the 81st Street Studio at the Met.

Gerrit Rietveld’s Zig Zag chair (1930), reconfigured as a baby bassinet. Courtesy of Adam Weintraub and Mishi Hosono.

Where do you buy most frequently?

Adam: The internet has changed our collecting habits. We used to pride ourselves on unusual finds in New York and Tokyo, but that is getting harder and harder to do these days. The online auctions allow us to see pieces that are on the other side of the globe, and to search for specific designers or chairs that we might otherwise never be able to find. Collectors now can track down nearly anything from anywhere in the world.

What is the most impractical chair you own?

Adam: Most of our chairs would be considered impractical! We certainly have a lot of uncomfortable chairs, if that’s what you mean by impractical. Although some of our least comfortable chairs for sitting are very useful as side tables or laundry hampers. We have a Shiro Kuramata Koko chair from 1986 that would be considered impractical by most. It is a black ash minimal chair with a small chrome back support. The edges are very sharp, and so it is almost dangerous to sit on. However, we couldn’t resist as it shares the name of Mishi’s mother and also the name of our design firm.

Isamu Kenmochi, rattan round chair (1960), Alvar Aalto, Artek 69 chairs (1935). Courtesy of Adam Weintraub and Mishi Hosono.

What work do you wish you had bought when you had the chance?

Adam: When you are young, buying furniture seems like an indulgence. All too often young people settle for inexpensive furniture that they intend to “trade up” in the future. We have always tried to buy “real” pieces even when it seemed like a reach for us financially. One of our design mottos is “sit on a good chair.”

One chair we still wish we had bid on is the limited-edition Singer chair (1945) by Bruno Munari. It has a seat that is angled down as if you built it in perspective. Munari said it was designed for “very brief visits.” It captures our approach to children’s design since it is both playful and serious at the same time.

Antonio Citterio’s Luta chair (2000), left, and Marcel Wanders and Bertjan Pot’s Carbon chair (2004). Courtesy of Adam Weintraub and Mishi Hosono.

If you could steal one work of art without getting caught, what would it be?

Adam: An exciting part of designing the new children’s space at the Met was being able to walk through the galleries when the museum was closed. We often fantasized about what we would be able to carry out under our coats. One of the reasons we like to collect chairs is that (most) are multiples. Since our daughters were very young, they would go to art museums with us and say, “Wait, we have that chair!” So we sometimes already feel as if we are surrounded by our favorite artwork.

If we had to choose one work of art to steal, though, it would likely be something by the sculptor Isamu Noguchi. His background combining Japanese and American sensibilities, as well as his craft, have always been an inspiration for us and our work. He also tried his hand at playground designs and felt that designs for children were as important as designs for museums. Unfortunately for us, most of his pieces are a bit too big and heavy to put under our coats.