Art & Tech

Two A.I. Models Set Out to Authenticate a Raphael Painting and Got Different Results, Casting Doubt on the Technology’s Future

The technology has limitations when faced with artists with low output or when it comes to detecting frauds.

The technology has limitations when faced with artists with low output or when it comes to detecting frauds.

Adam Schrader

Two different artificial intelligence models trained to ascertain whether or not a work known as the de Brécy Tondo is by the hand of Raphael have turned up two different opinions, posing a challenge to the rise of the technology in art authentication.

An A.I. model developed by Hassan Ugail of the University of Bradford “undoubtedly” determined recently that a work known as the de Brécy Tondo is by the hand of Raphael. It is now on view for the first time at the Cartwright Hall Art Gallery in the U.K.

“Testing the Tondo using this new A.I. model has shown startling results, confirming it is most likely by Raphael,” Ugail told the BBC last month. “Together with my previous work using facial recognition, and combined with previous research by my fellow academics, we have concluded the Tondo and the Sistine Madonna are undoubtedly by the same artist.”

Then, a model created by Art Recognition—a company that offers the technology to authenticate artworks—found with 85 percent probability that the de Brécy Tondo was not painted by Raphael.

The Swiss company has previously used its technology to both verify the Flaget Madonna as an authentic work by Raphael and to assert with 92 percent certainty that Samson and Delilah (1609–10) might not be by the hand of Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens after all.

Carina Popovici, CEO of Art Recognition, told Artnet News in an email that she was surprised her study’s result “clearly contradicted” that of Ugail’s team.

“At Art Recognition, we train our network on images of an artist’s artworks, enabling it to learn the distinctive characteristics of that particular artist and recognize them in new artworks. The researchers at Bradford and Nottingham, as indicated in their publication, employ a neural network that learns facial features from a vast dataset of millions of faces,” Popovici said.

The authors passed images of the de Brécy Madonna and Raphael’s Sistine Madonna through their network, which resulted in a high similarity score.

“I am concerned that this situation could potentially undermine the progress we have made in the past five years in establishing A.I. as a mainstream method for authenticating art,” Popovici said. “Now, more than ever, it is imperative to stress the significance of adhering to rigorous scientific standards. Otherwise, the entire field of A.I. could face criticism, and we would all suffer the consequences.”

Italian school, after Leonardo da Vinci, copy of Salvator Mundi (ca. 1600). Image courtesy Christie’s.

Experts told Artnet News that they believe A.I. will never fully replace traditional authentication methods because the limitations of the technology have revealed themselves more and more when it is applied to works other than Old Masters.

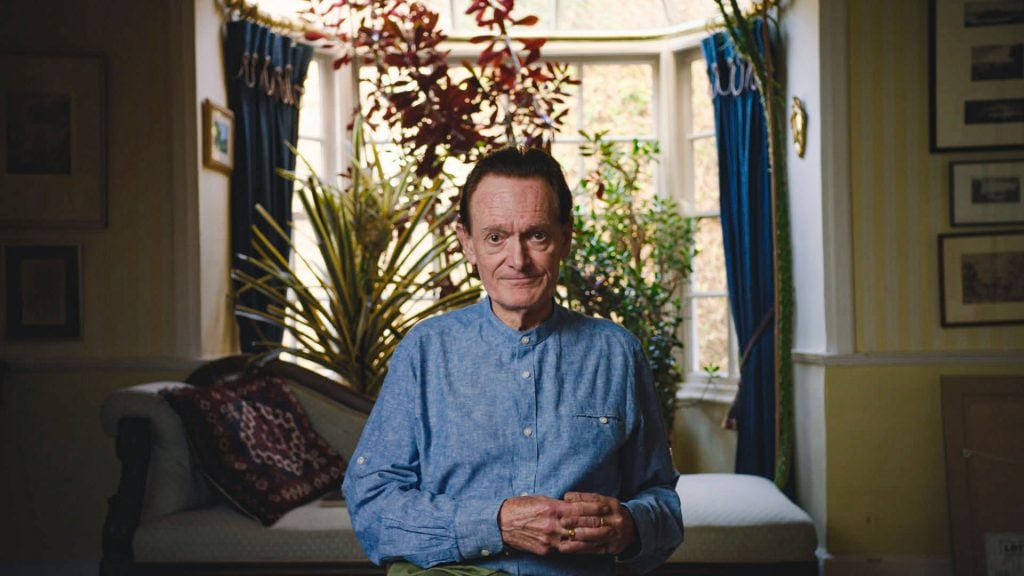

“Ultimately, there will always be a place for human judgment,” art historian Martin Kemp, a leading authority on Leonardo da Vinci, told Artnet News. “Some traditional historians were reluctant to accept when machines could inform them about the underdrawings. That roughly got shaken out of the system now.”

He views A.I. as “another tool in our armory,” such as pigment analysis and x-rays to examine underpaintings. But A.I. could have a hard time analyzing old masterworks such as Salvator Mundi that are “heavily damaged,” Kemp added, “and the damage sometimes is differential.”

He also suggested that A.I. could fail in attempts to authenticate artists like Titian or Leonardo, whose style varied from a simpler technique earlier in his career to “fine layers of very fine glaze” later in his career. Raphael, on the other hand, was “much more consistent.”

Martin Kemp, a Leonardo expert from Milan, in The Lost Leonardo. Photo courtesy of Sony Pictures.

Larry Silver, an art historian at the University of Pennsylvania who worked on the authentication of Flaget Madonna, said he believes Art Recognition’s dataset for authentication “worked better” than human authentication could.

“This is an early painting by Raphael and on a small scale. I’m not sure, however, that the A.I. training model is sufficiently nuanced to identify a work correctly by an artist whose style changed over the course of his or her career,” Silver said, putting Raphael in the same category Kemp did with Leonardo.

“I believe that the use of A.I. is on the horizon for auction houses, museums, and galleries,” Silver said, adding that “the intervention of a human interpreter is always necessary.”

Art Recognition was established to reduce the clashing of human interpretations and egos, Popovici said, while injecting transparency into the authentication process.

She claimed that her first model, which she trained on images of known fakes by Wolfgang Beltracchi that she found online, had a 100 percent success rate in identifying forgeries not used to train the model.

Peter Paul Rubens, Samson and Delilah (ca. 1609/10). Collection of the National Gallery, London.

Among the other artists that could pose challenges for A.I. is Rubens, Silver said, because he worked with collaborators, particularly on larger-scale works. Vermeer is another one. “[He] was a very distinct artist so it’s not possible to train A.I. on his 30 paintings,” Popovici said. “So of course, it is crucial to have the opinion of an expert.”

An even greater new obstacle facing the authentication space is the increasing number of A.I.-generated images. How might A.I. authentication fare against a fake Old Master generated by an algorithm?

“Authentication using A.I. isn’t really doing authentication but just determining the style,” said Ahmed Elgammal, director of the Art and A.I. lab at Rutgers University and founder of Playform A.I. “It can fail miserably when presented with fake art in the style of the artists.”

He added: “You can tell between Monet, Picasso, and Van Gogh—that’s pretty straightforward. But when you get into a forgery, it determines whether the art is in the style of Van Gogh and does not authenticate how Van Gogh does work.”

While A.I. generators are “probably far away from physically generating something from scratch on canvas all the way through,” said Kemp, advances in technology mean detailed oil paintings can be printed as they were once painted.

According to Arnold Brooks, a printmaking professor at Brooklyn College, printers can now print with oil paints and could, for example, use A.I. to print the underpainting with original or historical pigments.

Forgers “have always been the first” to explore using new technologies, added Elgammal, “to make better fakes.”

Wolfgang Beltracchi with a forged painting supposedly by Max Ernst. Photo by Brill/ullstein bild via Getty Images.

The use of A.I. to authenticate art leads to yet another question: Could A.I. help police and law enforcement better identify art seized as part of their investigations?

“A.I. isn’t going to find something locked in a nondescript storage unit. At least not yet,” said Samantha Moore, the in-house counsel for the Artists Rights Society.

However, A.I. may show the probability a painting is stolen. Opportunities for aiding law enforcement are going to become more important as the technology’s popularity grows, experts believe. Popovici said Art Recognition does not yet have any law enforcement partnerships but did consult with the Zurich Police Department in Switzerland on one case.

Art Recognition has started training its models using A.I.-generated forgeries to teach the classifier to differentiate between human and synthetic forgeries.

“An A.I.-generated image can trick an A.I. censor,” Elgammal added. “The use of A.I. in identification and verification is promising but still in the early stages. Some of the claims about A.I. use in authentication can be fraudulent themselves.”

An FBI spokesperson told Artnet News the bureau “has always attempted to stay ahead of advancements in technologies that may be used in furtherance of a criminal act or threat to national security.”

“These advances continue to this day, particularly in the fields of artificial intelligence and cybersecurity.”

Price Check! Here’s What Sold—and For How Much—at Frieze Seoul 2023