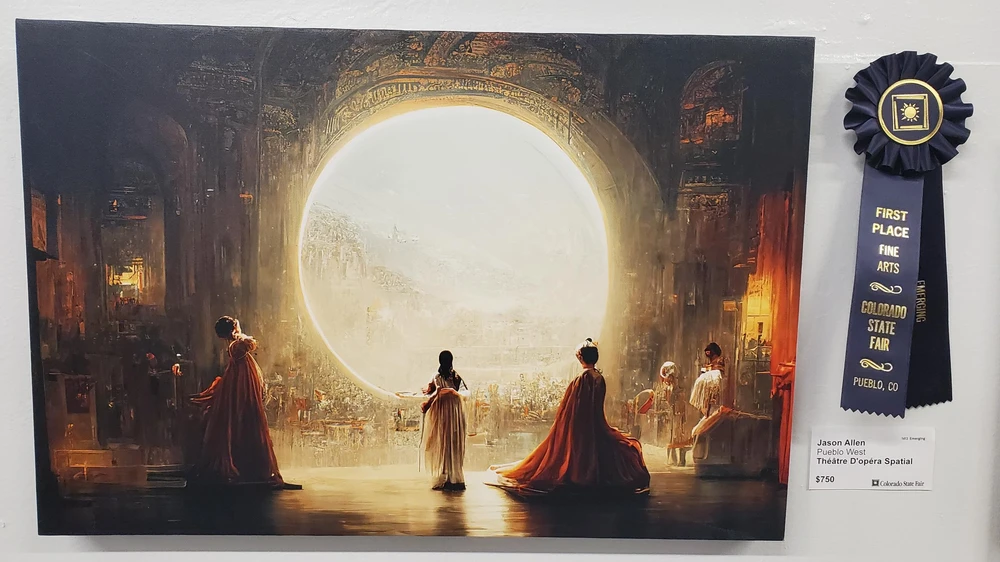

The debate within artist communities around art generated by artificial intelligence (A.I.) has intensified since Théâtre D’opéra Spatial by Jason M. Allen won the digital art category at this year’s Colorado State Fair Fine Art Show.

Shortly after fetching the $300 first prize, Allen told The New York Times: “Art is dead, dude. It’s over. A.I. won. Humans lost.”

His winning work had been made using Midjourney, one of the many A.I. text-to-image programs that have become available to artists and amateurs over the past year. Others include DALL-E 2, Stable Diffusion and Craiyon. Anyone following their development will have noted the stunning speed with which the computer programs have learned to make increasingly coherent, high-quality images.

One of the main criticisms is that the A.I. models have been trained on datasets containing copyrighted artworks pulled from the internet without permission. Vocal opponents, like the digital artist RJ Palmer, have posted works showing the similarity between original and A.I.-generated artworks on Twitter.

In many cases, an A.I. can easily recreate the styles and ideas that artists have spent their careers developing in response to just one well-worded prompt.

Artists, designers and illustrators have spoken out on Twitter, questioning the ethics of these generators, and fearing the possible impact of this new technology on their livelihoods, as well as on how audiences value their craft.

“A lot of the development behind A.I. art tools is based on the notion that making art is tedious grunt work, which simply isn’t true,” animator and designer Eva Eskelinen told Artnet News.

“Like with any craft, there are aspects that can be helped with a variety of tools. But to replace the creation process entirely misses the whole point for many artists. To many, it is a fun, emotional, human experience,” Eskelinen said. “Making art is complicated because it’s not just about the output, we’re interested in the creation as well.”

“I’ve viewed many who participate in making A.I. content as particularly cynical and nihilistic,” she added. “They view A.I. as inevitable, but it is not, unless we allow companies responsible for their development to do whatever they please and I don’t think we should. Many don’t have an ounce of respect or admiration for other artists either, because they fundamentally don’t understand how much really goes into the craft.”

The backlash has prompted some online art communities, like Inkblot Art and Newgrounds’ Art Portal, to announce that A.I.-generated artworks are no longer welcome on their sites. Larger platforms, like DeviantArt and ArtStation, have not yet followed suit.

Scott Stoller, general manager of the Colorado State Fair, told Artnet News that every year the board of commissioners review the requirements for competition entry. “I anticipate much conversation around this topic,” he said of the board’s decision to include art made using A.I. in 2023 and beyond. “I can speculate there will be some sort of acknowledgement of A.I. art in next year’s competition requirements.”

One of the voices in defense of A.I.-generated art is Daniel Rourke’s, a lecturer in digital media at Goldsmiths university in London.

“A.I. is just a set of tools composed of algorithms, data and interfaces,” he told Artnet News. “As we come to terms with A.I. in many aspects of our lives, so—as happened with computers or so-called ‘new media’—the idea and the tool itself will partially fade into the background.”

“Artists will play a big part in aestheticising A.I.; in making it comprehensible to a wider audience,” Rourke added. “In the meantime, there will be good and bad art made with these A.I. tools.”

Fabio Catapano, an artist making generative art and other computer-generated imagery (CGI), sees similarities between the advent of A.I. art and the arrival of photography. “The artistic act is in the intention not just in the outcomes,” he said. “It will for sure impact artists, commercial artists and many others, as every technology does. The art community will adapt after the drama phase.”

Mario Klingemann, a well-established artist who has been working with machine learning for many years, told Artnet News that he does not feel threatened by the influx of A.I.-generated art.

“We are currently getting buried in a whole lot of bad kitsch and low-hanging-fruit work with mass appeal, but in my opinion this is simply the natural way these things go,” he said. “After a phase in which everybody gets used to this new visual normality, those who are able to create outstanding work with the same tools will be recognized and, as usual, it will be just a few.”

As for artists not working with A.I., he also suspects they won’t have much to worry about long-term. “At least those with talent,” he said. “Once the initial shock-and-awe effect of the novel A.I. capabilities has worn off and people learn to see again, the craft and detail of handmade art will actually receive more appreciation.”

“Those who do mediocre work might want to revisit their life goals or up their game, since that is definitely the area in which the average A.I. is getting better and better,” he warned. “For those artists, I would recommend the ‘If you can’t beat them, join them’ approach.”