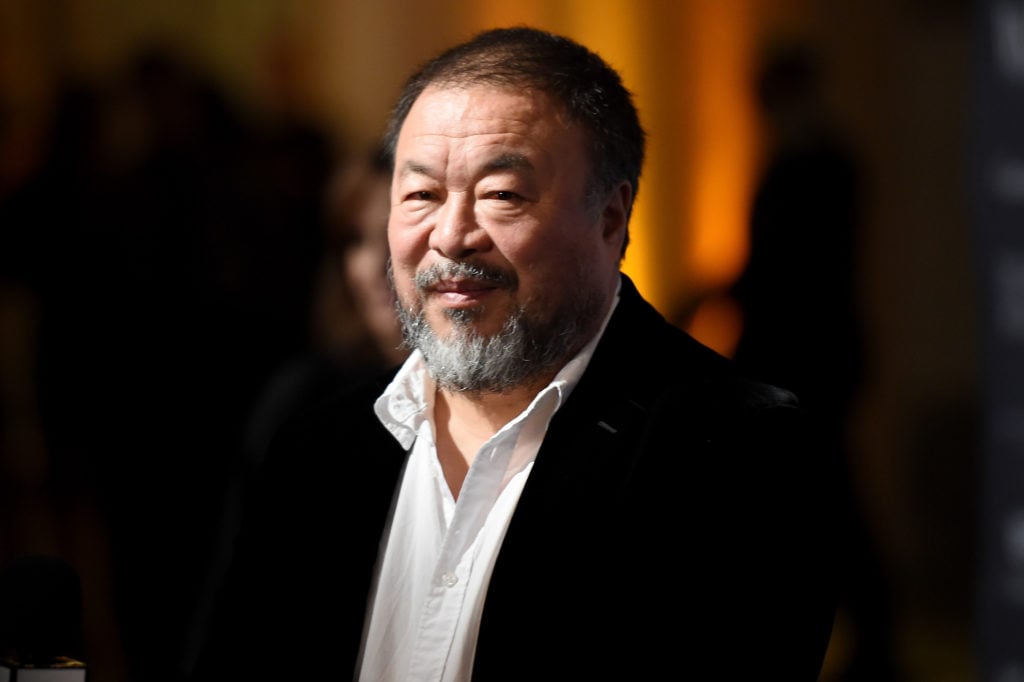

Earlier this year, Chinese artist Ai Weiwei was in the midst of directing an opera in Italy and producing three documentaries when the coronavirus pandemic hit the country. As lockdown orders were put in place, Ai decamped with his girlfriend and young son to Cambridge, outside of London, to self-quarantine.

At the end of April, Artnet News’s editor-in-chief, Andrew Goldstein, spoke to the artist via Skype to discuss the tectonic worldwide shifts inaugurated by the virus.

Click here to listen to an audio recording of this interview on the Art Angle Podcast.

How has your experience of the coronavirus been?

I was in Rome around the middle of February working on the opera, and once the city began shutting things down, it stopped all of our work there. I’m here with my girlfriend and my son in Cambridge, and there’s no school, but for me personally, I don’t see much of a difference. As an artist, I always work on my own—yes, my studio in Berlin is shut, and people are working from home, but at the same time, I’m producing a film in China, so through the internet, we can still do just about everything.

You are uniquely prepared for this crisis as an artist because you began working on multiple platforms many years ago, so if an opera you’re working on gets derailed, you still have your documentary or sculptures you can work on. I know you’ve actually been working on a documentary about COVID-19 since February. What inspired that project?

Ai Weiwei, Soleil Levant (2017). Photo by David Stjernholm courtesy of the Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen.

I never create anything, I just try to cope with the situation at hand. When I had just moved to Europe, I had to cope with the refugee crisis and the only way to learn and understand the situation is to be involved. I’m learning so much every day, I find new information and then I have to think about it, and to see what is different than it would be in a normal situation. You also have to study things about human history. You know, the same type of crisis has been happening throughout history, so you have some kind of perspective.

But this is really beyond what anyone could imagine, no one is prepared for a situation like this. You can see it from a state level and from a global level. Usually you have a crisis that is regional, but we’ve never had a global situation like this. We’ve been talking about globalization for decades, but this is truly the most impressive practice of the new order of the world. We are all somehow affected by it, and it will continue to affect our lives for quite some time.

As we know, the disease broke out in Wuhan and then spread throughout China before radiating out over the rest of the world. It’s now in over 100 countries. How well do you think the Chinese government has been handling its response to the coronavirus?

It’s very dramatic. The Chinese government tried to cover it up for a period of time—the most crucial period of time—but that has been kept silent. They were also sending out some misinformation about how this virus would not transmit from human to human, so that is a huge tragedy. They still don’t understand the nature of the virus, and they’re trying to keep it secret to gain some time for political reasons, and gradually the world will figure out what is really going on.

China very successfully controlled its main problem because with its military and its authoritarian society, they can do anything to prevent this kind of disease because there are basically no human rights or freedoms of speech there. So everything can be done in very sealed conditions. The so-called “free world” of democratic societies had such a hard time making everybody aware of the problem and how to deal with it.

Chinese President Xi Jinping chairs a teleconference and delivers an important speech after the field inspection of the epidemic prevention and control work in Wuhan, central China’s Hubei Province, March 10, 2020. Photo: Ju Peng/Xinhua via Getty Images.

You’ve been writing a lot of op-eds recently that have been very powerful, and you can see your thinking evolve on this subject. You’ve written that this is setting up a real ideological and civilizational struggle between the West and China in that China has proven that its huge advantages in terms of being an authoritarian country has helped it, in its own reporting, put a quick end to the rise and spread of this disease. At the same time in the West, leaders have been struggling to work cohesively because of the problems of democracy. In China, there is already a martyr to the cover-up in the person of the young Dr. Li Wenliang, who ultimately died himself. So what do you see as the parameters of this emerging struggle?

The struggle is that China only has a hammer, so whatever you say is a nail, they just use the hammer to smash it. And that’s quite effective because there’s no protection for negotiation on the humanitarian level. Now they don’t know how many are dead or how bad it is—there’s no open information and there is no trust. They don’t think trust is essential for their society. When there’s no voting, and no independent judicial system, no independent media, that functions as a very primitive type of a mafia world.

So when you start to discuss China, the Western societies just don’t understand it, but the problem also comes from the West, because do they really want to understand it? I don’t think they do. It’s really the difference between birds and snakes.

The West enjoys the ability to have business with China because of the size of the market and the unrestricted labor laws. They can get the job done that cannot be done in the West, relating to workers’ protections or environmental protection—all of those issues are nonexistent in China. So the West doesn’t say anything bad about Hong Kong or Taiwan, and they have their top companies working in China. So even today, when China makes such a dramatic disaster, the West needs something from China, and the criticism in mainstream sites is very soft and casual, because they are so beholden to the country. China knows that very well, and that’s why it has become very arrogant and very opaque. But it’s very clear, capital plays the game, just like the line in the movie All the President’s Men: “Follow the money.”

Ai Weiwei, “Sunflower Seeds” in the Tate Modern Turbine Hall. Courtesy of Tate.

The stakes of dealing with the coronavirus on a global scale seem to be competition between authoritarian rule and democratic rule. And this is where it becomes even more critical that China has been less than forthcoming about the real nature of the virus. In one of your op-eds, you said “the disease may not be a natural disaster.” What do you mean by that?

On the surface we say that it’s democratic world or authoritarian world. But if you look a little bit further at what Karl Marx was writing about capital, you understand that in today’s world, capitalism is still playing the role that affects every aspect of life, both in the so-called democratic world and authoritarian world. China is not really a communist society, but state capitalism. So we have a deeper problem here. You cannot just isolate that as a coronavirus problem.

Is there any particular line of inquiry that you’re exploring about the virus in your documentary?

No, my documentary is observational, it’s not a political argument, it’s too complicated an issue for a documentary to make that kind of argument. I think we need a lot of discussion, and a lot of understanding about our time and our future.

Ai Weiwei’s Remembering at the Haus der Kunst. The work is made of 9000 backpacks to remember the victims of the 2008 earthquake. JOERG KOCH/DDP/AFP via Getty Images.

Your most consequential body of work to date comes from a previous official coverup where you investigated the deaths of thousands of students who were killed when schools built by the Chinese government collapsed in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. This led to your famous internment, being beaten by the police, and eventually fleeing the country in 2015 after a sustained campaign of harassment. Are you worried at all that doing a documentary on the coronavirus could be dangerous considering the political stakes that you’ve laid out?

The danger is always there, but it’s bigger than what I’m facing personally. You see the whole world in danger now, and it’s always there. It just depends on what angle you measure it from.

This pandemic seems to have united the world in a strange way, because this disease doesn’t discriminate between countries, although it does discriminate between demographics within those countries. Do you think the virus could potentially bring us closer together?

It’s a very interesting notion. Fear will always unite people. But you can see politicians always use that to play into that fear and profit from it. I think that’s a very possible danger in a police states, where the control of civilians will become even stronger. Big data will be much stronger after this crisis.

Recently you told the Guardian that “an artist must also be an activist aesthetically, morally, or philosophically.” What do you mean by that?

If artists are a part of the human conscience, they must be very alert. It’s like when the virus penetrates a body—there should always be a frontier to protect the system, and art functions like that.

Ai Weiwei, S.A.C.R.E.D. (2013), a six-part work composed of (i) S upper, (ii) A ccusers, (iii) C leansing, (iv) R itual, (v) E ntropy, (vi) D oubt. Courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

And what do you think artists should be doing in times of crisis like this if you’re the nerve endings of the body?

If art has any value, it should have a certain kind of mission in protecting our humanity, because you’re not scientists, you’re not on the “front line.” It’s not practical. Art is about how humans can be called a very special species that have the capacity to love and dream and really associate with one another.

One of the op-eds you recently wrote was illustrated by a picture of the virus by your son Lao. Is he following in his father’s footsteps as an artist too?

No. I feel very fortunate that he’s not following so much. He made that long before the virus happened, he used screws twisted into a fresh apple, but now it’s dried out and it looks just like the model of the virus, so when the newspaper asked me to give them an image i thought the sculpture resembled that very well. But I think the new generation really looks at the world differently—they have different language I don’t understand that well. I’m just trying to cope with the situation.

Being an artist has given you a very rich but extraordinarily complicated life. Why is it that you’re so glad your son is not going to be an artist too?

I think art is a very dangerous world. The nature of art is to take steps of uncertainty into the unknown, and you will never be satisfied.

You’ve been using social media to document this strange time we’re living in, posting the obituary everyday from the Daily Bergamo, the local paper of Italy’s hardest-hit city, and also photos of spring flowers blossoming in England. But you’ve also had some fun with your Instagram feed and you’ve posted a new sculpture you made. Can you tell me about that?

In a moment when I had nothing to do, I was walking around the green spaces in Cambridge and I found an old tree trunk, so I told my son to put it on the back of his bicycle and take it home. He had no clue what I wanted to do with it. I used the middle part with no cracks and I worked with him using very limited tools, so we barely made a roll of this kind of toilet paper (laughs). You know this is the most unnoticed household object but has now become a strategic national weapon! This is amazing, nothing could be a better readymade than the political situation we’re facing.