Museums & Institutions

Uli Sigg’s Formidable Collection at M+ Is a Beacon of Hope in a Changing China—Even If a Particular Ai Weiwei Work Is Notably Absent

See inside one of the most highly anticipated—and closely watched—museums in Asia.

See inside one of the most highly anticipated—and closely watched—museums in Asia.

Vivienne Chow

Artworks by Chinese artist-activist Ai Weiwei and items that may be deemed politically sensitive are now on view at the long-awaited M+ museum, which opens to the public in Hong Kong this week. But the mega-institution has much more to offer as it attempts to craft an Asian-centric narrative of art and culture.

Opening to the public on Friday, November 12, after nearly 14 years and several delays, the museum billed as Asia’s first global institution dedicated to contemporary visual culture unveiled its full array of opening exhibitions in a press preview on Thursday morning.

Since the Hong Kong-focused exhibition and the design and architecture show had been revealed during earlier previews, what drew the most attention at the media event this week was the exhibition of the Swiss collector Uli Sigg’s vast holding of Chinese contemporary art. It is being seen as a litmus test for how much creative freedom remains under the national security law implemented last year.

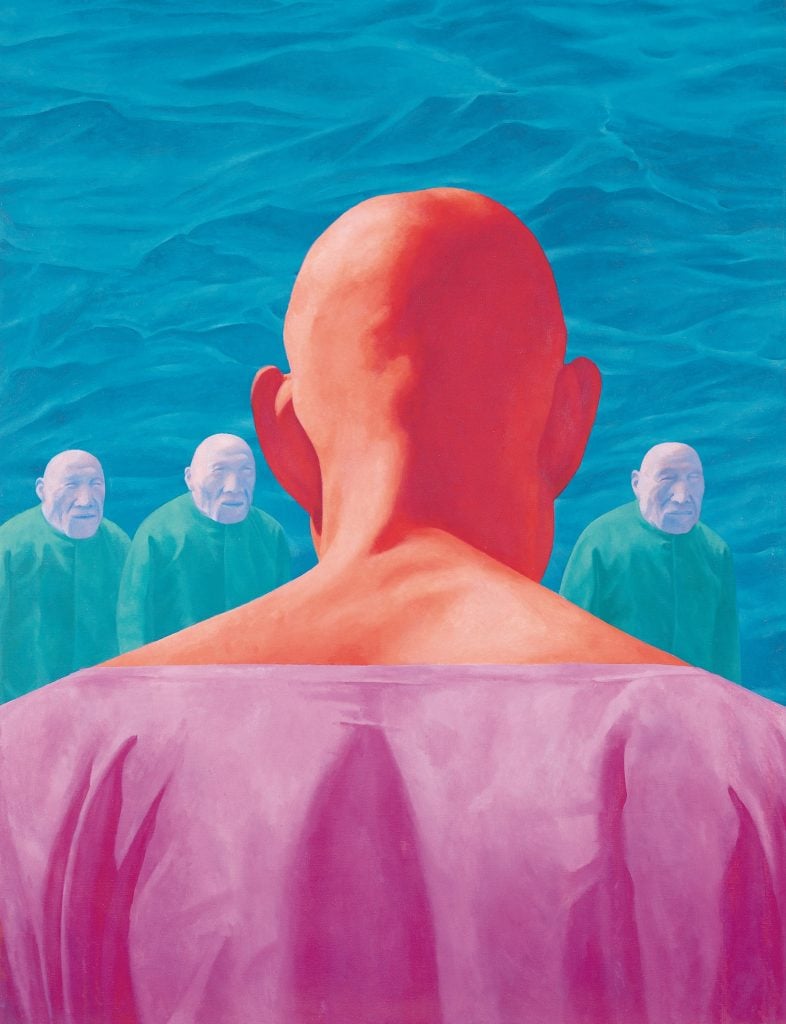

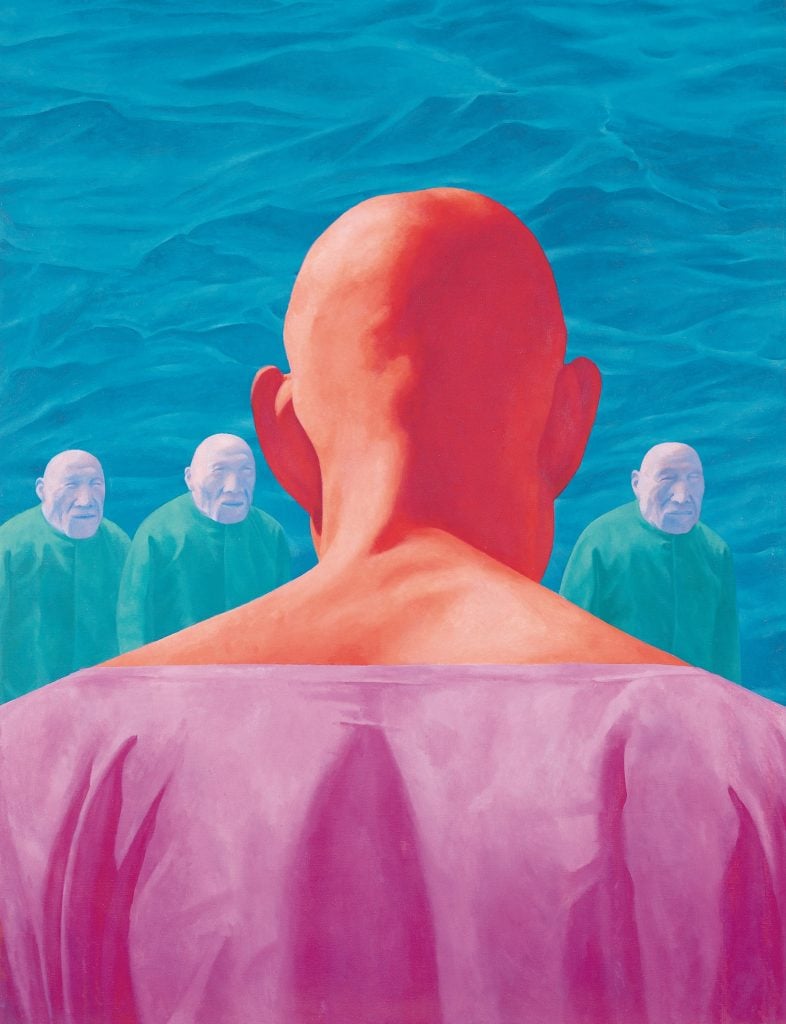

M+ Sigg Collection exhibition: (Front) Whitewash (1995–2000) Ai Weiwei. (Back, left to right). Everybody Connects to Everybody (1997) Yue Minjun. 1996.1B (1996) Fang Lijun. Mask: Rainbow (1997) Zeng Fanzhi. Photo: Rachel Wong.

“We will uphold and encourage freedom of artistic expression and creativity,” said Henry Tang, chair of the board of the West Kowloon Cultural District Authority, which runs the arts hub where M+ is situated. “But artistic expression is not above the law. As a public museum, we have the responsibility to comply with the law and respect a society’s cultural standard.”

Tang noted that the museum does have controversial artist Ai’s work on display, but that they “do not have that middle finger picture.” He referred to Study of Perspective: Tian’anmen from 1997, which depicts the Chinese dissident artist raising a middle finger at Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. Earlier this year, the photograph came under attack from the city’s pro-Beijing politicians who accused the work of “spreading hatred against China” under the new national security law.

Lin Tianmiao Braiding (1998). M+ Sigg Collection, Hong Kong. By donation © Lin Tianmiao. Photo: Dan Leung.

The absence of that famous image from the exhibition “M+ Sigg Collection: From Revolution to Globalisation” by no means undermines the value of the show, which aims to be a chronological survey of the development of Chinese contemporary art from the 1970s through the 2000s.

The exhibition has drawn from the 1,510 artworks in the M+ Sigg Collection that were largely donated by the Swiss mega-collector in 2012. Sigg had assembled his encyclopedic collection of contemporary Chinese art during his years as a diplomat in China (aside from the donation, another 47 were acquired by M+ for HK$177 million ($22.7 million)).

“We have been working on this for almost 10 years,” Pi Li, the Sigg senior curator of M+, said during the media preview. “This show tells you about the development of Chinese artists step-by-step, about how to understand the art of China, and how to generate a new understanding of China.”

The show features more than 200 items on display in the Sigg Galleries which are located on the second floor of the 700,000-square-foot museum building designed by the Swiss architecture firm Herzog & de Meuron in collaboration with TFP Farrells and Arup. The Sigg exhibition showcases a number of rare art treasures beside the well-known paintings from the Chinese contemporary art superstars such as Zeng Fanzhi, Zhang Xiaogang, Yue Minjun, and Fang Lijun.

Wang Xingwei New Beijing (2001), M+ Sigg Collection exhibition. Photo: Rachel Wong.

Among the highlights is Fusuijing Building, a small painting from 1975 by Zhang Wei that reflects the lack of artistic freedom during the Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s, which ended only a year after the work was created.

Other notable works include Drama of Two Culture Formats Merge, a monumental ink on rice paper work by Gu Wenda from 1985. Lin Tianmiao’s Brading from 1998 is a stunning large-scale installation by one of China’s most famous female artists that addresses the multi-layered texture of Chinese history and contemporary society. Another eye-catching work is Wang Jinsong’s Standard Family (1996), a series of photographs capturing “standard families” under China’s one-child policy.

A blue-painted room is dedicated to the documentation of some of the most provocative performance art China has ever seen: photography and video recording of To Add One Meter to an Anonymous Mountain, a 1995 nude performance delivered by 10 artists from the Beijing East Village community formed in the early 1990s led by Zhang Huan. A series of eight photographs by Ma Liuming from 1998, showing the artist walking on the Great Wall naked, is also on display.

“M+ Sigg Collection: From Revolution to Globalisation” in Sigg Galleries. Photo: Lok Cheng, M+. Courtesy of M+, Hong Kong

There are two works by Ai on display in the museum, Whitewash (1995–2000), an installation made of ancient jars, and the 10-hour video work Chang’an Boulevard (2004). And while his work about Tiananmen Square is notably absent, Wang Xingwei’s painting New Beijing (2001) is on view—slyly referencing the famed news image that depicts wounded students being rushed to the hospital on the back of a flat-bed bicycle during 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown. An annual vigil commemorating the event in Hong Kong and the group behind the event were forced to disband this year.

The museum also unveiled Antony Gormely’s expansive installation Asian Field, which the British artist created with 300 villagers from Guangdong in five days in 2003. Though a total of 200,000 clay figurines were made, only around half of them are on display due to space constraints. It took 23 helpers and 15 days to install the work.

Antony Gormley: Asian Field (2003). Photo: Rachel Wong.

The institution has adopted a unique approach to publicity, observers noted. Rather than giving a wide range of press interviews, the museum brought a large number of social media influencers to take happy pictures prior to Thursday’s press preview. Journalists covering the preview were also barred from sitting at the opening ceremony attended by top officials, and were arranged to watch a live streaming of the event in a separate room.

Despite the lack of international visitors due to Hong Kong’s stringent travel restrictions, the museum is expecting over a million visitors in the coming year—free-of-charge in the first 12 months after the institution opens.

Additional reporting by Rachel Wong.