People

Akeem Smith on How He Navigates Between Fashion and Art, and His Videos Celebrating Jamaican Dancehall

“No Gyal Can Test” seeks to capture a simple message: "time is of the essence."

“No Gyal Can Test” seeks to capture a simple message: "time is of the essence."

Annie Armstrong

The hero image of Akeem Smith’s first solo exhibition, “No Gyal Can Test” at Red Bull Arts Detroit, embraces a striking contradiction: Carlene Smith, familiarly known as Jamaica’s first Dancehall Queen, stands triumphantly in a sheer, skintight black bodysuit on skis in the snow of Park City, Utah.

“She must have been freezing,” remarks Smith fondly. “This is the epitome of not code-switching.”

That brazen spirit carries throughout “No Gyal Can Test,” the first major solo show by the rising star, which spans both floors of Red Bull Arts’s gallery space. It also includes an off-site installation, Soursop, at Woods Cathedral, a (modestly) refurbished church that was originally built in 1919.

Akeem Smith, Soursop (2020). Installation view at JTG Detroit Project in the former Woods Cathedral, April 2021. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Courtesy of the art ist, New Canons, and Red Bull Arts.

“Conceptually, [the show] grows legs based on where it’s at,” Smith explained. He had originally planned for the show to debut in a traditional gallery space, but, when approached by Red Bull, the 29-year old artist saw the value in showing this work at a space that came with it’s own historical baggage. “There’s a lot of visual aesthetic, Black visual aesthetic history, and sonic expression here in Detroit that is very interesting and correlates with Jamaica in a way.”

Smith grew up bouncing between Brooklyn, New York and Kingston, Jamaica, where his family owned the clothing atelier Ouch and his grandmother co-owned a nightclub. A self-described “party animal,” Smith carries on his family’s fashion industry legacy in Brooklyn, working, among other things, on Hood by Air.

Akeem Smith, Memory (2020). Installation View of “Akeem Smith: No Gyal Can Test” at Red Bull Arts New York, 2020. Photo by Dario Lasagni. All artwork courtesy the artist and Red Bull Arts.

Smith explains that his career in fashion is what pays the bills—but getting his art practice off the ground is his main focus. “In this day and age, people are not too judgy about, ‘Oh, you do that too?’” he notes. “But I’m never ever trying to blend the worlds.”

For “No Gyal Can Test,” Smith returned to Jamaica to collect odds and ends that were connected to his memories from childhood: certain types of breezeblocks; ornately twisted wrought-iron bedframes and benches; shutters with chips of colorful paint barely clinging to sun-bleached wood. These are the source materials Smith then used to create the elaborate architectures within which his most well-known work—his collaged videos of found footage from various dancehall clubs in Jamaica—is shown.

Akeem Smith, Sugar Minott (2020). Installation view at JTG Detroit Project in the former Woods Cathedral, April 2021. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Courtesy of the art ist, New Canons, and Red Bull Arts.

Social Cohesiveness (2020), the artist’s longest video piece (with a run-time around 30 minutes), is also his most blatantly political. Projected against three screens, one of which is a sculptural interpretation of the Jamaican flag, the film commences with the mantra “The more u give, the more u get…”

Sometimes humorous, sometimes devastating, the film draws parallels between the scattered and hazy nature of childhood memories and the equally feverish memories of a long night out.

Akeem Smith,Social Cohesiveness (2020). Installation View of “Akeem Smith: No Gyal Can Test” at Red Bull Arts New York, 2020. Photoby Dario Lasagni. All artwork courtesy the artist and Red Bull Arts.

The film features the kind of animated cartoons that are nostalgic fare for ’90s kids, dancing alongside portrait footage of club-goers in Kingston. On a third screen, Princess Margaret is shown visiting her colonial subjects in Jamaica with a formal wave.

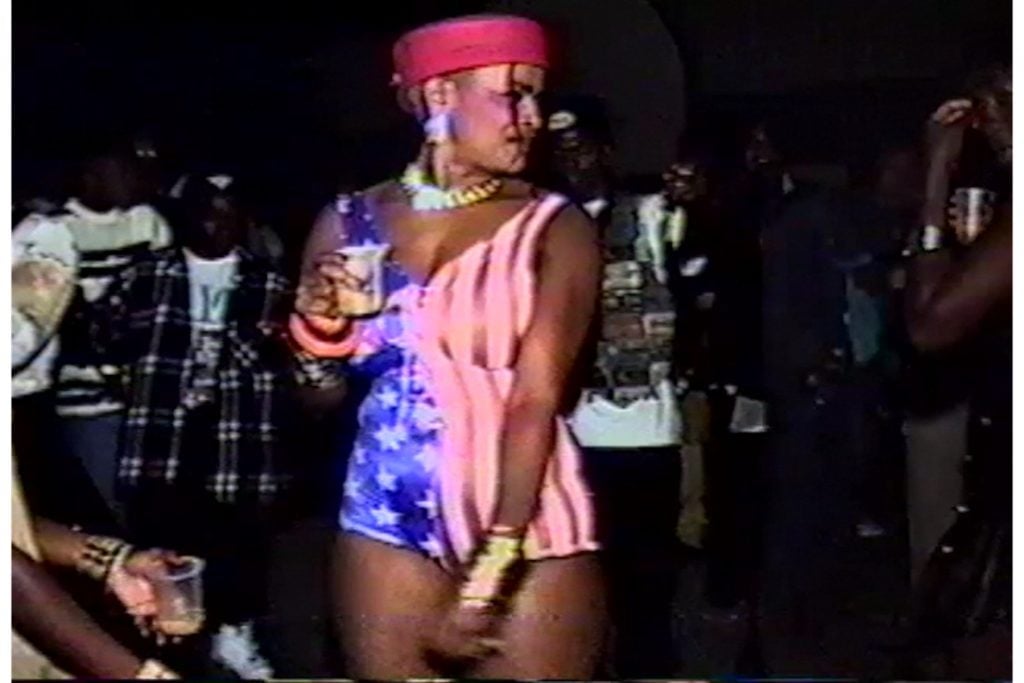

The film comes to its apex on the morning of September 11, 2001, as the imagery of planes hitting the twin towers, seared forever into the world’s collective memory, is juxtaposed with a woman in pink gyrating, the timestamp in the far left corner reading “8:30AM 9/11/2001.” Voicemails to loved ones from those aboard the planes play at a muffled distance as each screen toggles between the images of the initial impact, the woman in pink dancing in slow motion, and an elevator going perpetually upward.

“I miss a world where something like 9/11 can be happening and you don’t know what’s going on. That’s such a thing of the past,” says Smith.

There are four video works in “No Gyal Can Test,” all tied together by a distinct editing style that calls to mind British artist Mark Leckey’s famed video piece Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1999). Smith first saw the cult-classic work at MoMA PS1 in 2016. “I watched that shit and I was like, ‘How am I going to beat this?’” he says, laughing. “I want people to feel how I felt when I first watched it.”

The subtle political messaging implicit in both artists’ portraits of niche club cultures—rave and dancehall, respectively—reminds viewers that these subcultural spaces in nightlife emerge from a legitimate need for expression.

Akeem Smith, Social Cohesiveness (2020). Video Still. Courtesy of the Artist and Red Bull Arts.

“Seeing that camaraderie that happens at 6:30 in the morning is just so relatable,” Smith explains. “I know I’ve felt that emotion, and it’s not so site-specific to Jamaica or dancehall. Like I say, the flashiness of dancehall is just to lure people in. What it’s really about is how time is of the essence.”

After the Detroit show closes on July 30, Smith is headed to Honduras for a thirty-day silent retreat. The artist has done such retreats before, but never for so long. “I’ve done ten days, I’ve done 12 days. I never reached the fourteenth day,” he says. “I always try and I never reach it. You get in this space where it’s like, I don’t want to be too above the clouds. I don’t want to see things too clearly.”