Art Collectors

What I Buy and Why: Hong Kong Fintech Exec Alan Lau on the Very Real Dangers of Not Reading an Artwork’s Condition Report

See inside the studio of the veteran collector.

See inside the studio of the veteran collector.

Vivienne Chow

A version of this article originally appeared in the Artnet News Pro spring 2022 Intelligence Report.

Alan Lau doesn’t mind a busy space. His Hong Kong studio, which he uses as part office, part personal escape, is packed to the brim with art—especially complex installations. As chairman of WeSure, Tencent’s fintech insurance business, Lau is particularly interested in the space where art, creativity, and technology intersect. This focus has led him to dip his toe into the world of NFT collecting alongside acquiring old-fashioned IRL art.

The 47-year-old former investment banker turned consultant also keeps himself busy on multiple art-related committees: He serves as a board member of Hong Kong’s M+ museum and the Guggenheim’s Asian art circle as well as co-chair of Tate’s Asia Pacific acquisition committee.

Earlier this year, we visited Lau to find out how he continued to build his collection in lockdown, why he missed out on buying an Avery Singer, and what he thinks is the best way to display NFTs.

Alan Lau’s art-filled Hong Kong studio. Photo: Paul Yeung.

What was your first purchase (and how much did you pay for it)?

A graffiti work by “King of Kowloon” Tsang Tsou Choi. I think it was HK$30,000 ($3,850).

What was your most recent purchase?

My most recent physical art purchase was a George Condo painting from his show at Hauser & Wirth in London last year. On the digital side, it was an NFT by Jason Boyd Kinsella paired with a psychological portrait that came out of a Zoom interview we did about my personality. It was a long creative process. Initially there was no NFT, just a painting and an Instagram filter. I love the way Kinsella uses psychological tools like the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator to dissect human archetypes and then applies his unique visual language to portraits.

Which works or artists are you hoping to add to your collection this year?

So many! Gisela McDaniel, Miguel Payano, Mehdi Ghadyanloo. I’ll also pay attention to new NFT projects, especially collaborations between crypto and traditional brands, like Bored Ape Yacht Club x Adidas.

How big is your NFT collection?

I usually don’t sell physical works, but I have sold some of my NFTs. Think of NFTs as trading cards or stocks—they can be bought and sold with just one click. I have one by Pak and another from Takashi Murakami’s Clone x NFT collaboration with RTFKT Studios that I don’t plan to sell.

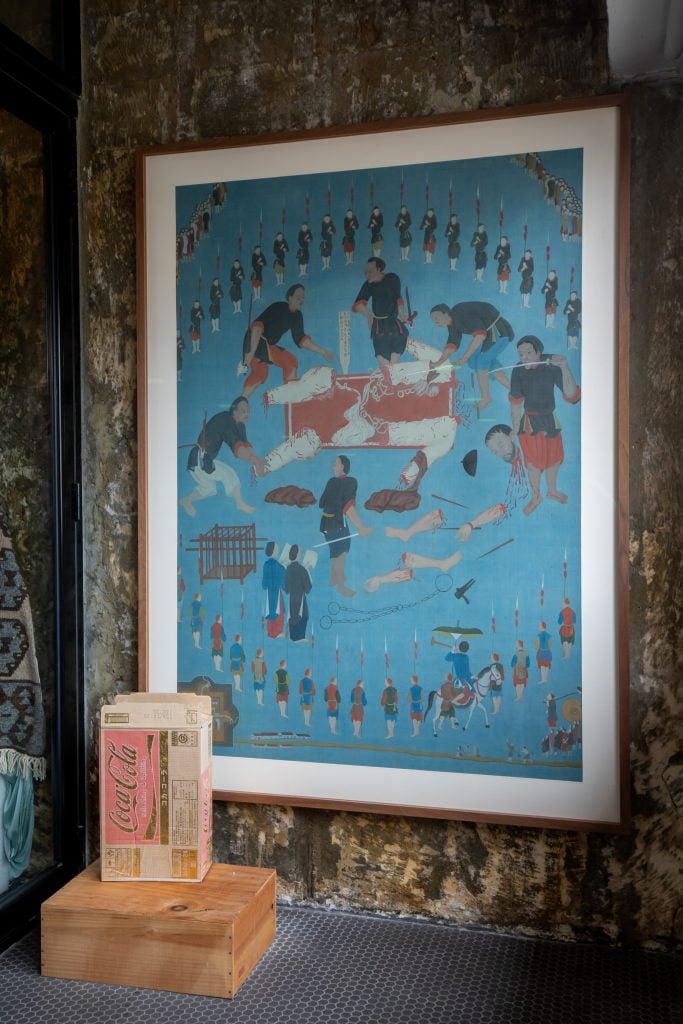

From top: Danh Võ’s May (2015) and Coca-Cola (2014). Photo: Paul Yeung.

How do you show your NFTs?

I don’t know how I’m going to show them yet. Do you show them on your smartphone screen? Maybe 12 months from now, the whole world will be using NFT profile pictures. There’s also the question of ownership. Do you have to see the works all the time in order to feel that you own it? Or is it enough to know that you own it?

What do you get out of owning NFT works?

It’s about joining a community. For example, owners of the Murakami NFT get to join a Discord channel for verified owners. This social-media dynamic and community aspect is something I’ve never experienced in all my years of art collecting.

Are NFTs art?

NFT is an art form, broadly defined. But not all NFTs can be classified as contemporary art. There are only a handful of works that could be exhibited in a museum context, such as those by Pak, since they are a combination of art, design, and economics, playing with the art-world system. Beyond the nomenclature, NFTs offer a new approach to engagement, creation, and ownership.

Olafur Eliasson’s Sunset Door (2005). Photo: Paul Yeung.

What is the most expensive work of art that you own?

Maybe not the most expensive, but my Ai Weiwei neolithic vases are certainly my most dear. I acquired them over a decade ago. They are from 5,000 B.C., now dripped in industrial paint to symbolize destruction and rebirth. This object has lived on for 7,000 years, so I am merely a custodian—and I better not break or damage it!

Where do you buy art most frequently?

Galleries and art fairs. But with the pandemic, 100 percent of my purchases over the past two years have been done online after looking at PDFs. This is definitely harder for more textured works. But galleries are upping their game to make better images, videos, and even live feeds so collectors can get a better grasp.

Alan Lau poses with Yayoi Kusama’s The Passing Winter (2005). Photo: Paul Yeung.

Is there a work you regret purchasing?

In my first year of collecting, 12 or 13 years ago, I bought a scroll from one of the major auction houses. When I unboxed it, I saw that it had two parallel holes. Apparently, someone mistakenly drilled through it during installation. When I asked the auction house about it, they said the damage was listed in the condition report, which of course I didn’t read. Lesson learned: Buyer beware—and always request and read the condition report before you buy.

What work do you have hanging above your sofa?

Xu Bing’s Square Word Calligraphy, which I commissioned in the early 2000s. It was a fun process to decide together what prose to write.

What is the most impractical work of art you own?

Anyone who has come to visit me knows that most of my collection is impractical! Erwin Wurm’s One Minute Sculptures, Korakrit Arunanondchai’s denim mannequin, Yin Xiuzhen’s Portable Cities suitcases, Olafur Eliasson’s Sunset Door, Anri Sala’s hanging drums that play themselves—all of these take up a lot of space, or require complex installation. But installation works were my first love. So while they are impractical, this is the art I live with.

Clockwise from top: Wolfgang Tillmans’s Torso (2013); Tillmans’s Collum (2011); Ai Weiwei’s Table With Three Legs (2005); and Liu Heung Shing’s The First Bottle of Coke, Beijing (1981). Photo: Paul Yeung.

What work do you wish you had bought when you had the chance?

A painting by Avery Singer. On a New York trip many years ago, when a fellow collector said he needed to run off to Singer’s studio and look at the last few works left, I decided to see more museum shows. That didn’t turn out to be the smartest decision. But I’m happy that we now have an Avery Singer at M+, so I can go there and quench my thirst.

If you could steal one work of art without getting caught, what would it be?

A Piet Mondrian. I want a large one, so I may need to go with a few art handlers. That’s art I can live with forever.

To download the full spring 2022 Artnet Intelligence Report, available exclusively to Artnet News Pro members, click here.