On a recent visit to the Albertinum museum in Dresden, the guestbook was flipped open to an entry that read: “You have three rooms dedicated to Gerhard Richter… Take some more works out of the depot!!”

Such emphatic demands from the public are common occurrences here. In the six years since its newest director, Hilke Wagner, arrived, the guestbook has been filled with weekly criticism (and occasional praise), while the museum fields further feedback via phone calls, emails, and in community meetings.

Richter—who has a dubious reputation in his birth city both for defecting to West Germany from what was then a part of the German Democratic Republic, as well as for his abstract paintings, a frequently snubbed art form in the former East—is one recurring subject. But the public has an even longer list of grievances about what should and shouldn’t be on view.

The museums’ critics have also been casting doubt on whether Wagner, who is a West German, has been programming East German art appropriately, or whether she is suited for her role at all. Among the museum’s more vocal challengers is the far-right Alternative for Deutschland party (AfD), which has honed in on culture as a key battleground in the former Eastern states, a region that is seeing a resurgence of far-right extremism. In Dresden last November, the city declared a “Nazi emergency”—and the Albertinum has become a cultural flashpoint.

Performance zu Ehren von Erika Hoffmann und ihrer Sammlung am 31.08., 01.09. und 02.09.2018 in Albertinum und Kupferstichkabinett von Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. Photo: Oliver Killig.

Building a New East German Canon

The museum serves in many ways as Dresden’s memory bank, reminding residents of the city’s complicated and painful history. The East German riverside city was once a glimmering pre-war cultural capital, and in many ways it still is: Its state collections boast a formidable holding of art, ranging from antiquity to modern and contemporary masterpieces. Once a former treasure trove of Saxonian kings, it fell under Nazi party control in the mid 1930s, before being badly damaged during World War II, alongside the entirety of Dresden, a pain that still resonates with many who live there.

Much of the collection was recovered in the postwar years, and the museum was a vital player in establishing and presenting East German artistic canons—with the Albertinum fashioning itself as a “documenta of the East,” as Wagner puts it, throughout the 1960s to 1990s. Today, Wagner and her team are trying to forge a way forward while keeping those aspects of its past alive. This includes presenting a more pluralistic view of East German art history than some traditionalists might like.

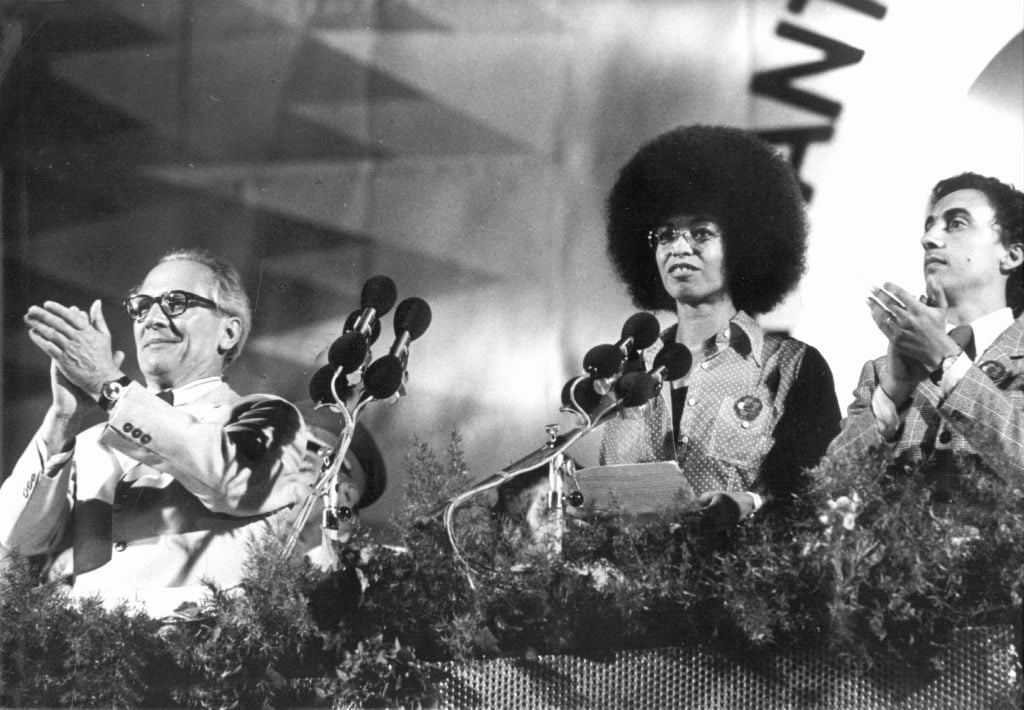

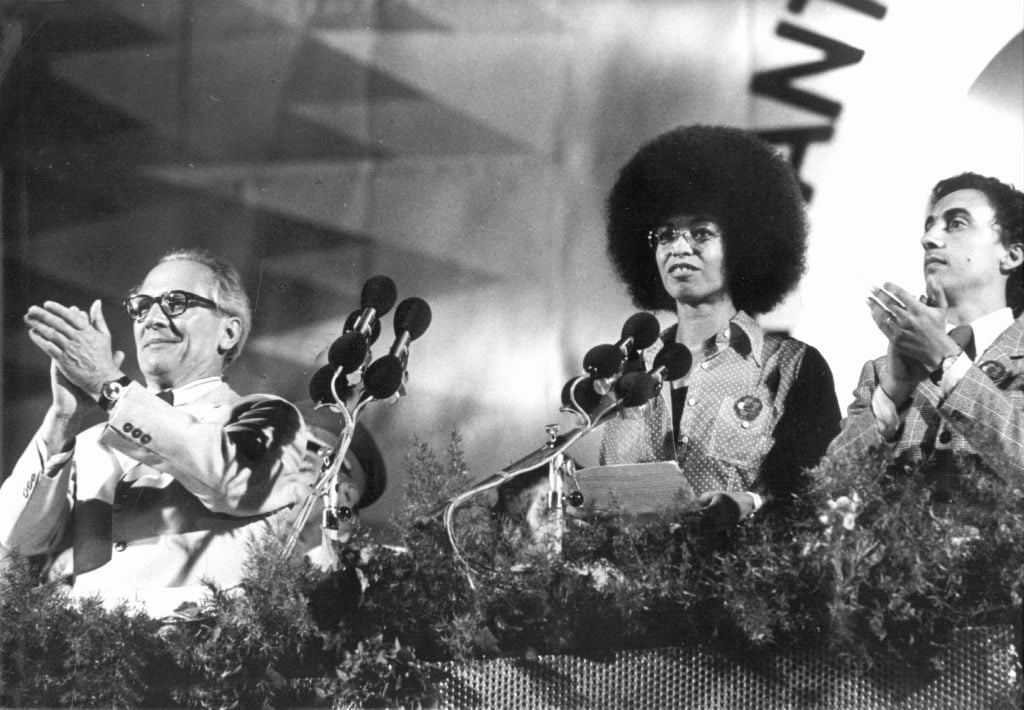

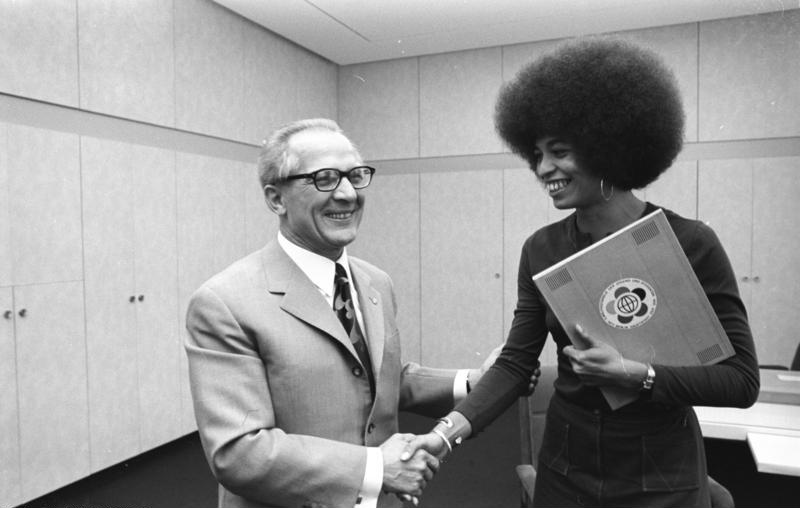

General Secretary of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany, Erich Honecker, with civil rights activist Angela Davis in East Berlin in 1973. The Albertinum will open a show focused on the legacy of Angela Davis in East Germany on October 10 called “1 Million Roses for Angela Davis.” Photo by Giehr/picture alliance via Getty Images.

This week, the museum opens a major group show, on October 10, which explores the political and symbolic power of the Black Power activist and philosopher Angela Davis, who was a hero in East Germany and embraced by the Communist nation. The show, “1 Million Roses for Angela Davis,” seeks to revise what Davis represents to both East German and German identity on the whole.

“We do not want to completely shock people or drive them away,” says the show’s curator, Kathleen Reinhardt, but rather “take something that is here and that people hold dear,” and then “look at it more closely, contextualize it, and then unfold it in a different way.” Reinhardt, who is from the former East, is working with archival material as as well as commissions and works by contemporary artists including Arthur Jafa, Slavs and Tatars, and Senga Nengudi that address themes in Davis’s work.

The Albertinum frequently pairs its permanent collection with contemporary works: A bright painting by Kehinde Wiley stands out in a hall of stately pre-modern portraits. Elsewhere, Paris-based Kapwani Kiwanga’s draped fabric sculptures draw on the pastel palettes in German painter Max Slevogt’s exoticized 1914 portraits of his travels in British-occupied Egypt.

Another recent exhibition, “The Medea Insurrection. Radical Women Artists Behind the Iron Curtain,” which closed in 2019, spotlighted work by female artists that went beyond the bounds of state-supported art in the Eastern Bloc at the time, including figures like Geta Brătescu, Magdalena Abakanowicz, and others who did not fit neatly into the canon of Soviet-era art, which officially championed figurative realism.

“Arriving here in Dresden, I had been fascinated by the variety of East German art that was still to be discovered,” Wagner said, referencing performance, film, or abstract works that were not championed during the German Democratic Republic (GDR). “But this, I learned, was not the kind of ‘GDR art’ people wanted to see.”

Kapwani Kiwanga Oriental Studies (2019) on view at the Albertinum around 1914 paintings by Max Slevogt. Courtesy the Albertinum.

‘We Need to Talk’

Soon after Wagner joined the museum, in 2014, she began receiving threats and hate mail in increasingly strong wording. “People had the feeling that I, as a Western German, was attempting to explain to them what good East German art was—they felt that was an arrogant gesture,” she says. That same year, outside the museum walls, the anti-immigration group Pegida began their weekly anti-immigrant, anti-refugee demonstrations near the museum.

Not long after, the AfD became more vocal in its criticism of the museum’s new program. In 2017, the political party submitted an official request for the museum to “count” the number of East German works of art it had on view. (The museum complied with the ensuing government mandate and found that, in fact, there was actually more East German artworks—three times more—than the party had thought.)

“People who are fighting for Eastern German art are not always right-wing thinkers—it is merely a strategy that the AfD is using to get to the East German people,” Wagner says.

To try to work through some of the public’s concerns, the museum held a community forum in 2018 and 2019 titled “We Need to Talk.” The series was intense and heated.

Panel discussion on how to handle East German art in the museum, a part of the talk series “We Need to Talk.” Courtesy Albertinum.

“First, the Western Germans stormed out shouting, and then the Eastern Germans stormed out and smashed the door behind them,” Wagner recalls. But, on the whole, she found the project constructive. “We didn’t necessarily reach a point of agreement, but we cleared up misconceptions,” she says. “We learned a lot from each other.”

The public feedback made clear that a “narrative of suffering” is often what qualifies art as East German, Reinhardt says—”works that seem to say that people suffered under socialism.” They did not want the museum to “challenge any simplistic victim narrative with additional nuance and context,” Wagner adds.

So the museum strove to find novel solutions: When the public asked for paintings that showed the Dresden bombings, it complied, but paired them with anti-war works by Maria Lassnig and Marlene Dumas.

Supporters of the anti-Islam PEGIDA movement (Patriotic Europeans against the Islamisation of the Occident) demonstrating in front of the Albertinum museum in Dresden during a visit by Angela Merkel. Photo: Sebastian Kahnert/dpa/AFP/Germany OUT.

An Unlikely Icon in Angela Davis

Most former East German citizens will recall the state-sponsored “Free Angela Davis” postcards, petitions, and marches, which demanded the activist’s freedom after she was jailed in New York in 1972 on terrorism charges. Shortly after her release, Davis visited East Germany, where she was received as a revolutionary hero, greeted by 50,000 cheering citizens.

The show “1 Million Roses for Angela Davis,” which will open at the Albertinum’s Kunsthalle im Lipsiusbau, examines the unlikely role that the leftist cultural icon plays in today’s divided Germany. It considers the principles she stood for and their “push and pull” against East German identity today. Even as Dresden has emerged as a cradle for the resurgent far-right, Davis has remained an admired figure.

“People here on the extreme right would not dare to attack Davis, because she is a hero, so a really strange and highly complex situation occurs in terms of the mechanisms of appropriation and racism,” says Reinhardt, who is curating the show. Alongside the exhibition, which draws a line between the rise of socialism after the war to the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020, the museum will also host workshops and events focused on racism.

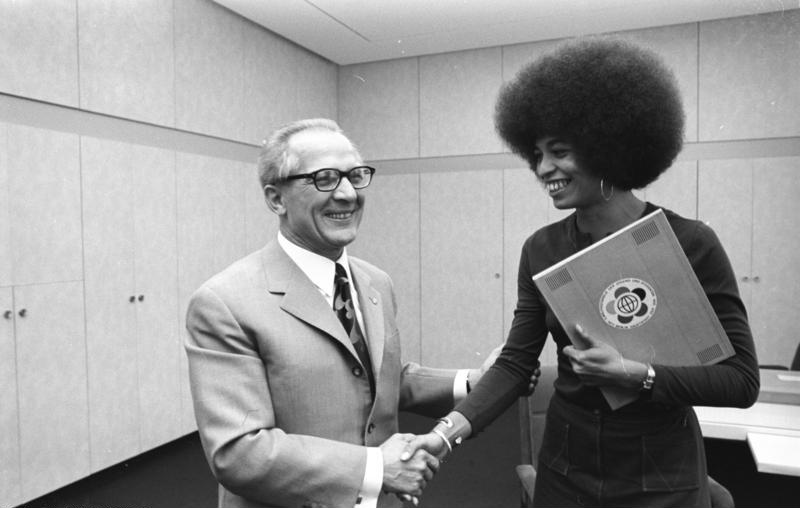

Socialist Unity Party of Germany first secretary Erich Honecker shakes hands with civil rights activist Angela Davis in 1972 in East Berlin. Photo: German Federal Archive (Deutsches Bundesarchiv).

The exhibition, which includes archival material from the Davis campaign in East Germany as well as new commissions by contemporary international artists, aims to “destabilize a history of socialist glory,” Reinhardt says.

“The ‘Other’ was only welcomed as external, special, foreign, as a guest in this uncritical white imaginary that shaped—and still shapes—East Germany, and maybe German identity as a whole,” says Reinhardt.

These themes dovetail with other initiatives at the museum, including an ongoing effort to diversify the works in its collection. Despite the museum’s well-established prestige and curatorial might, Wagner has been struggling to find affordable East German art, a category that is rapidly increasing in price.

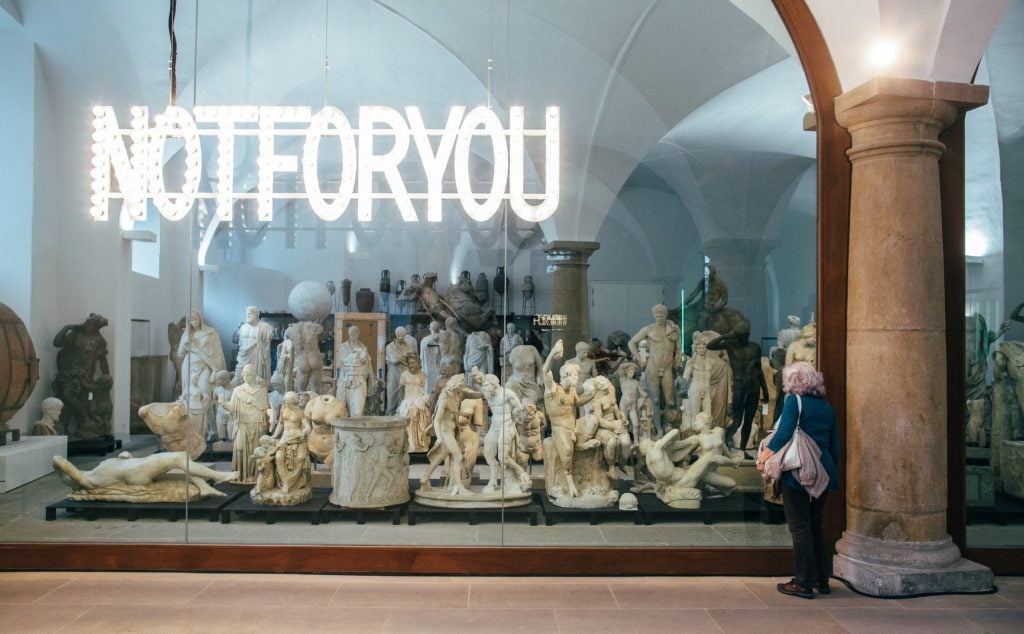

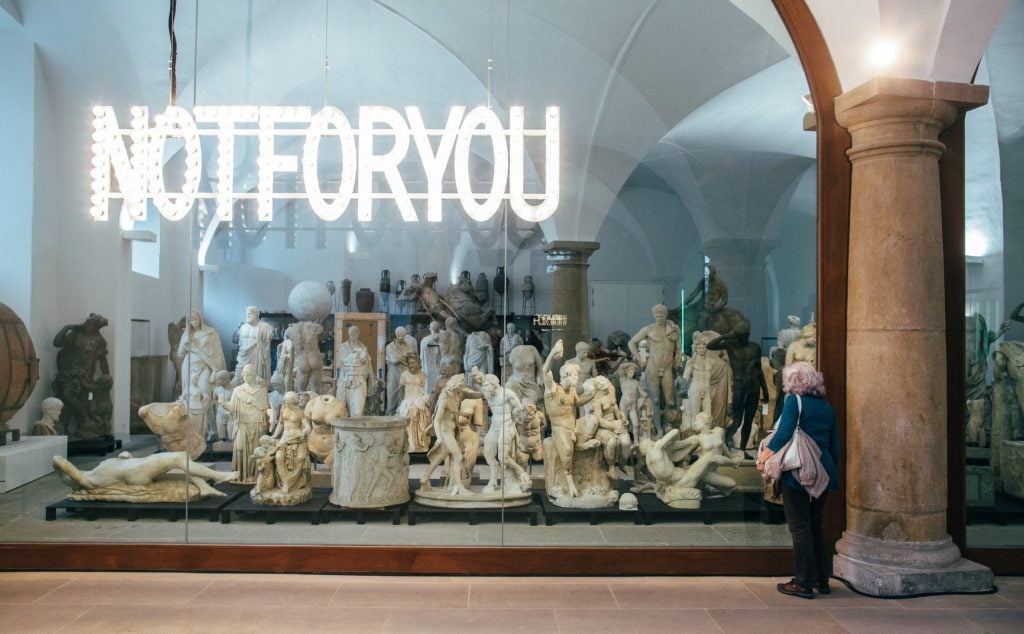

Exhibition view of “1 Million Roses for Angela Davis. Courtesy the Albertinum.

Exhibition view of “1 Million Roses for Angela Davis. Courtesy the Albertinum.

“It’s terrible because large international institutions are now acquiring East German art, and we are out of the race,” Wagner says. “We are not talking about a single Expressionist work of art that is worth millions. With $300,000 or $400,000, we could acquire quite a lot of works that would diversify the collection.”

But foundations, at least for the time being, do not seem particularly interested in taking up the cause and aiding the museum’s collecting efforts. “We have to preserve for the next generations a more multi-perspective view of the arts from the former country,” Wagner says, referring to the GDR. As of now, the collection has a large concentration of “official” art from the period, but that excludes many female or dissident artists.

Despite the challenges Wagner faces, she says she’s encouraged about the direction of the museum and the potential for learning within its walls.

For East Germans, art was always something “really existential,” she says. “It still reverberates today. Here in Dresden, you can really reach all kinds of social communities, attitudes, and generations with art,” she adds. “This is a really big chance for us.”

“1 Million Roses for Angela Davis” is on view from October 10, 2020 until January 24. 2021.