Art History

To Celebrate Albrecht Dürer’s 550th Birthday, Here Are 3 Fascinating Facts to Change the Way You See His Legendary Self-Portrait

One of the most famous self-portraits of all time is, not surprisingly, full of intrigue.

One of the most famous self-portraits of all time is, not surprisingly, full of intrigue.

Katie White

“Whatever was mortal in Albrecht Dürer lies beneath this mound,” reads the epitaph on Northern Renaissance master Albrecht Dürer’s grave. The elegy’s suggestion of his superhuman status is not without merit.

When Dürer died in 1528 at the age of 56, his fame was unparalleled for any artist from north of the Alps. A contemporary of Michelangelo, Dürer espoused the traditions and techniques of Renaissance Italy (and had traveled there) while placing creative emphasis on printmaking and continuing the cultivation for the Northern tradition of meticulous detail.

Perhaps most fascinatingly (at least to our contemporary moment), Dürer was the first artist to master the self-portrait. Other artists had included their likenesses before Dürer, but Dürer returned to the subject repeatedly, rewarding it with its own tropes and techniques.

Albrecht Dürer, Self-Portrait at the Age of 13 (1484). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

He painted three self-portraits in this lifetime and completed several others as engravings and drawings (the first he made silverpoint at the age of 13). Far and away the most well-known of any of these portraits is the last he painted, made at the age of 28, in 1500. The image is widely regarded as one of the most influential self-portraits in history.

As this week marks the 550th anniversary of Dürer’s birth on May 21, 1471, we decided to take a look at this infamous image. Here are three facts about Self-Portrait (1500) that might change the way you see Dürer’s painting—and the art of self-portraiture in general.

Part of this painting’s fame comes from a seeming provocation: Dürer has depicted himself with a striking resemblance to Jesus Christ (or at least, to the figure of Christ as known through art history).

In Dürer’s lifetime, it should be noted, it was believed that there had been a (now-debunked) eye-witness account of Jesus found in the “Letter of Lentulus,” written by Roman official Lentulus, a purported contemporary of Jesus. The epistle had first been published in the 1400s. While today it is believed to be a forgery, its description of Christ’s features had great influence on how he was imagined—and Dürer’s long-haired, bearded, youthful features match Lentulus’s account.

But is this just coincidence? Even more than the self-portrait’s features, it’s the composition that really hammers the association home. Until this time, fully frontal half-length portraits of the kind in the 1500 Self-Portrait had been reserved almost exclusively for depictions of Christ.

Albrecht Dürer, Self-Portrait (Madrid) (1498). Collection of the el Museo del Prado.

Most portraits of the age were in keeping with the three-quarter position, as seen in Dürer’s Self-Portrait from just two years before. There, he depicts himself as a refined dandy—a very different image from the intense, head-on presentation.

As opposed to the Italian landscape in the background of the 1498 self-portrait, the more famous 1500 self-portrait has a flattened, icon-like black background as well. Dürer had most likely seen—or seen works based on—Jan van Eyck’s Vera Icon, which serves as a compositional jumping-off point for his self-portrait.

Copy after Van Eyck’s Vera Icon (1439). Collection of Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

Van Eyck’s now-lost panel links back to religious icons that seek to recreate the Biblical “true image” of Christ—that which was believed to miraculously appeared on St. Veronica’s veil after she dried his brow on the road to Golgotha.

Such devices certainly suggest Dürer claiming that he was an art god. Thus, in the 1940s, famed art historian Erwin Panofsky asked the question that continues to plague historians today: “How could so pious and humble an artist as Dürer resort to a procedure which less religious men would have considered blasphemous?”

But while that might seem arrogant, in the artist’s own time, a reverence for self was, in fact, perceived as the way to Christ. “Self-love and love of God exist in an uneasy symbiosis in pre-Reformation piety,” wrote Joseph Leo Koerner in his book The Moment of Self-Portraiture in German Renaissance Art, “Nicholas of Cusa, we recall, regards narcissism as the starting point for devotion. We embrace God, in whose images we are made, not initially because we recognize him as our creator but because we see his face as a reflection of our own, which we love above all else.”

Detail of Albrecht Dürer’s Self-Portrait (1500).

The decision of the 28-year-old Dürer to depict himself was startling in his time, both in his modern techniques and his decision to center himself as the subject. “The 1500 Self-Portrait enacts a kind of Copernican revolution of the image, where what was peripheral in the painting becomes central,” Koerner noted.

It’s not just that he put his own image at the center of the work, either. He also gave the artist’s signature a new prominence.

Detail of Albrecht Dürer’s Self-Portrait (1500).

Here, his signature with the year 1500 and an inscription “I, Albrecht Dürer of Nuremberg have portrayed myself in my own paints at the age of twenty-eight” appear on either side of Christ’s eyes, reinforcing the idea of the equivalence between artist and Christ.

Dürer’s unique, monogram-like “A.D.” signature, with a large A with a D beneath it, also had a religious and temporal association, calling to mind “anno domini”: “in the year of our Lord.”

Detail of Albrecht Dürer’s Self-Portrait (1500).

Many have noted the unusual hand gesture the artist is making as he pinches the fur of the coat. “It’s a beautiful, even perverse detail,” Jason Farago noted in a recent close read of the painting in the New York Times, “one that plunges this pseudo-icon back into the realm of the senses.”

In addition to its modern sensuality, the gesture also, once again, pointed to the rising self-image of the Renaissance artist. Dürer’s fur coat in the painting would have been associated with the upper classes.

Art historians have also posited that the coat is marten fur, commonly used in paintbrushes of the time. Dürer fingering the bristles thus would make a direct connection between the trappings of high social status and the labor of the artist.

Others have noted that Dürer’s fingers might echo the shapes of “A.D.” in a self-referential gesture.

Albrecht Dürer, The Man of Sorrows (1515). Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

There is still another interpretation of the mandorla (i.e. pointed oval) that Dürer forms with his fingers: It may be an allusion to the ostentatio vulnerum or crucifixion wounds. In particular, it mimics Christ’s side wound, the final wound inflicted by a Roman soldier who speared Christ’s side to confirm his death.

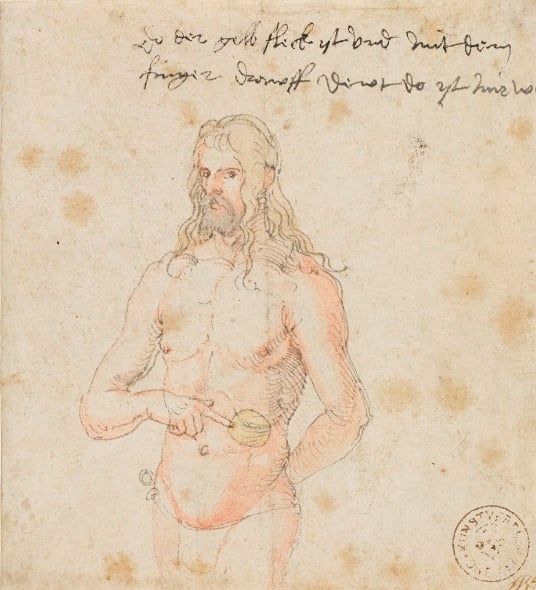

Paintings and sculptures that depict Jesus showing his wounds were a popular motif known as “Christ as the Man of Sorrows.” It was one with which Dürer was familiar, having created several of his own and even depicting himself as such in a later drawing known as the Bremen Self-Portrait.

Albrecht Dürer, Self-portrait, ill (1509/11). Collection of the Kunsthalle Bremen.

Theologically, the splitting of Christ’s side was believed to prefigure Adam’s chest being opened to take the rib used to form Eve. Thus, from the splitting of Adam’s side is born humanity, and in the splitting of Christ’s side is born the salvation of humanity.

In this sense, Dürer’s enigmatic gesture may once again be acknowledging God as the source of his own creative abilities. As Koerner explains, “the artist is divine only because God is Deus Artifex; man can create ‘new creatures’ rather than simply imitate created things, only because he imitates the creation of the world.”