Art World

Polish Painter Aleksandra Waliszewska Is Fascinated by Slavic Vampire Folklore. Just Don’t Call Her a Witch

We spoke with the artist, whose childhood reads like a novel.

We spoke with the artist, whose childhood reads like a novel.

Katie White

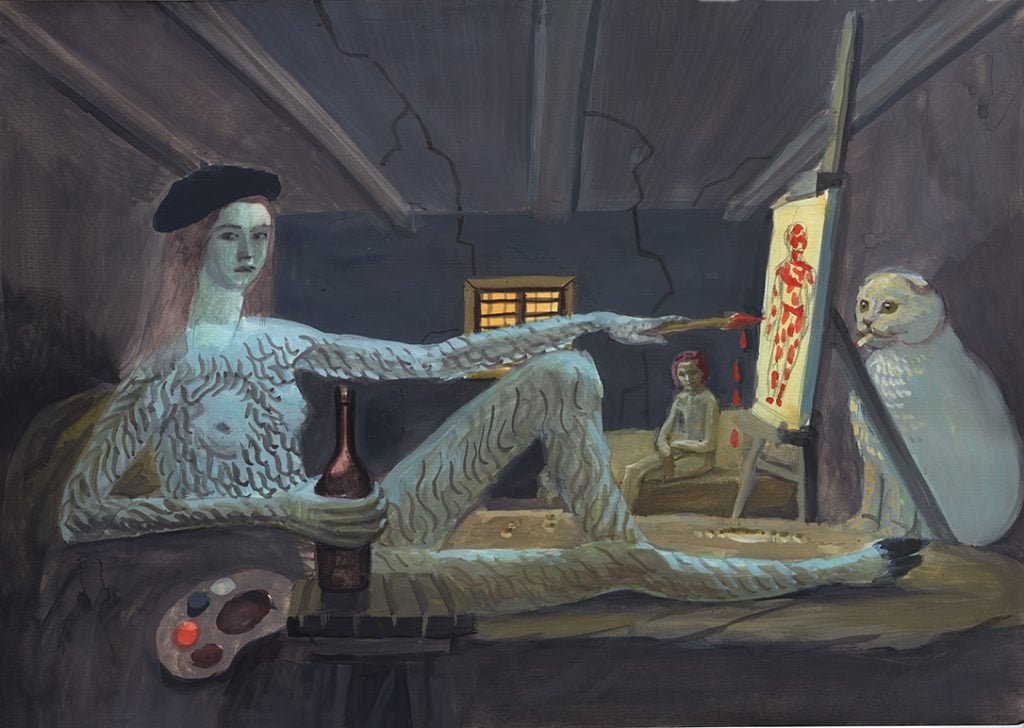

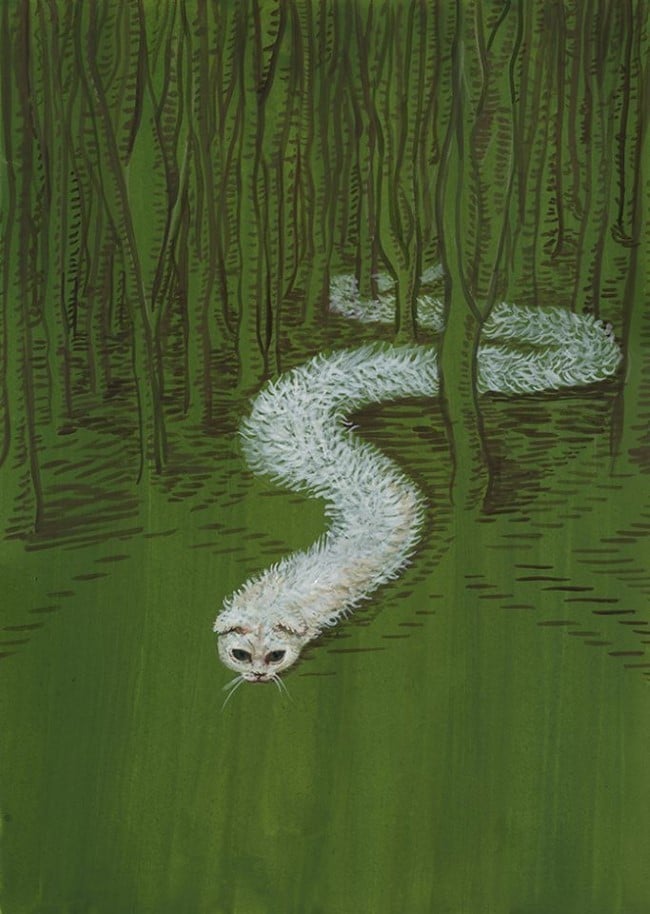

Polish artist Aleksandra Waliszewska’s muse was, for many years, her green-eyed cat, Mitusia. Mitusia, who had a calm disposition, died last year, but her likeness lives on in dozens of Waliszewska’s paintings and gouaches in a spectrum of guises: smoking cigarettes, writhing like a snake, even posing as a model.

These visions are variously beguiling, unsettling, and darkly amusing—and offer a quick introduction to Waliszewska’s particular insights and interests. The artist, who was born in Warsaw in 1976, where she continues to live and work, has cultivated an enigmatic style, combining Medieval hellscapes and Gothic romantic themes à la Mary Shelley with the bloody outlandishness of horror films. Mitusia is not the only recurring image: there are also humanoid goats and horses, creepy, carved-out faces, mutant spider-women, and a variety of disquieting nocturnal tableaux.

Aleksandra Waliszewska, Untitled (Mitusia). Courtesy of the artist.

The work has garnered many admirers. (Waliszewska has over 115 thousand followers on Instagram). Among these is Susie Cave, the fashion designer and founder of the Vampire’s Wife fashion label. In a blog post, Cave wrote: “I don’t think in all my time I have seen such a consistently terrifying vision of the subconscious world. Aleksandra reaches into some dark subterranean elemental place where all things happen, forbidden and beautiful both.”

Recently, Waliszewska collaborated with the Vampire’s Wife, on tee-shirts to be released on every full moon in a tribute to Mitusia’s legacy. (Her work can also be seen in “My Private Hell” at Company Gallery in New York, alongside works by Cole Lu, Robert Bittenbender, and Tobias Bradford. In 2020, her works were shown in “I Want to Feel Alive Again” at Lyles and King in New York.)

Aleksandra Waliszewska, Untitled (Mitusia). Courtesy of the artist.

Waliszewska’s childhood reads like a novel. She was born into a family of women artists: her grandmother, Anna Dębska, was a significant 20th-century sculptor, famed for her energetic, monumental depictions of animals, particularly horses. The passion was more than aesthetic. Dębska established one of the first private Arabian horse stud farms in Poland.

“She also seduced young men,” Waliszewska told Artnet News.

While still a child, Aleksandra began pursuing art (her earliest recollections include a self-portrait with a giant, toothy mouth, with animals lined up to get in).

“One of the clearest memories I have from that period is a drawing I made of a naked running lady. That was the beginning of a composition in which a bunch of naked ladies are shown running from flying saucers that are trying to catch them with lassos.”

She recalled a particular moment of pride regarding that picture. “My mother’s then-partner, who was nicknamed Rekin [Shark], saw the drawing and was sure it was by my mother, who is a sculptress with supreme drawing skills.”

Alexsandra Waliszewska, Untitled (2022). Courtesy of the artist and Company Gallery.

Soon after, the famed Polish psychologist Andrzej Samson took a liking to her works, and devoted an office wall solely to Waliszewska’s drawings. In 1986, her tenth year of life, she made her first sale.

“I got a pack of sesame snaps in exchange for a book full of drawings,” she said. “Whoever was dealing with me at that time is by no means a loser.”

While Waliszewska enjoyed a childhood of creative experimentation, she spent years struggling with the expectations of school.

“I was full of illusions regarding the coolness of the artistic world at the time. Luckily, school sobered me up,” Waliszewska recalled, noting that during an exhibition in her first year of high school, “someone wrote ‘LOUSY’ in golden ink under one of my paintings.”

Waliszewska soon committed herself to a rigorous course of self-imposed study.

“I went through many art books, comparing my skills to those of famous artists when they were my age. Picasso became a major point of reference.”

She went on a relentless run of crash courses with live models, making as many studies as possible. “I harassed my friends, created confusion among park-goers, and made a trillion self-portraits. No one was safe.”

Nor was everyone enthusiastic.

“I received a torrent of bad marks with comments that I was already over as an artist,” she said. So she cheated her way through entrance exams to make it into art school.

Alexsandra Waliszewska, Untitled (2022). Courtesy of the artist and Company Gallery.

She followed these years with enormous ambitions, and some accolades.

“I’d seen a lot of marvelous art and wished to paint like Piero Della Francesca or Masaccio. My paintings from this period brought me substantial financial success and some popularity. 2002 and 2003 were the culminating point of this chapter,” she recalled.

But not soon after, around 2005, she fell into struggles.

“This was the darkest time in my practice. I still painted for several hours a day, but I was totally dissatisfied with the effects,” she recalled. The breakthrough came in 2006, when she saw the Japanese animated film Tamala 2010: A Punk Cat in Space. Its heroine, Tamala, comes across a forgotten painting in a museum basement while looking for the bathroom.

“I saw that Japanese filmmakers can gracefully paint something I was torturing myself over for years over, and be better at it,” she said. “Right then, I took a break from ‘high’ ambitions.”

Today in her studio, Waliszewska paints surrounded by her grandmother’s animal sculptures and much more.

“I have a billion paints, a trillion art albums, and a hoarding problem. I start a new painting almost every day, but it’s hard for me to describe my process more closely. What I do originates mostly from my fascination with the art of the past.”

While she is reticent to give too much insight into the influences at play, she says early Renaissance art almost always appealed to her—scenes of hell and the apocalypse, particularly. Pieter Bruegel’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus is a particular favorite.

Generally, though, she believes art went downhill after the Quattrocento.

“Art has only become worse and worse. Despite this hopeless situation, I still paint, so the audience can at least find something new and interesting in my work,” she said. “Usually, though they’re disappointed.”

Alexsandra Waliszewska, Untitled (2022). Courtesy of the artist and Company Gallery.

Aside from animals, most of Waliszewska’s paintings and gouaches feature women who often bear a resemblance to the artist. She says she uses herself as an anatomical model, but when asked who these women are and why they’re here, she jokes: “I’d also like to know who these bitches are.”

She is deftly obtuse about the often frightening subject matter she presents: when I asked about the spooky factor, she asked me if I found the paintings scary. Well, yes, at least a bit. Perhaps that stems from her acknowledged interest in upiórs, Slavic folkloric vampires. But the artist stresses she doesn’t want to be associated with the modern witch movement.

“Bullshit I’d rather not be associated with,” she said.

For now, Waliszewskai is working to organize a forthcoming exhibition at the Warsaw Museum of Modern Art meant to open this June. The exhibition will feature nearly 200 works, alongside examples by Polish artists she admires. One of them, Marian Henel, is an outsider artist.

“He weaved enormous tapestries in a psychiatric hospital, mostly depicting the giant asses of nurses,” she explained. “Unfortunately not much remained of his work, but he’s definitely an artist of similar stature to Henry Darger.”