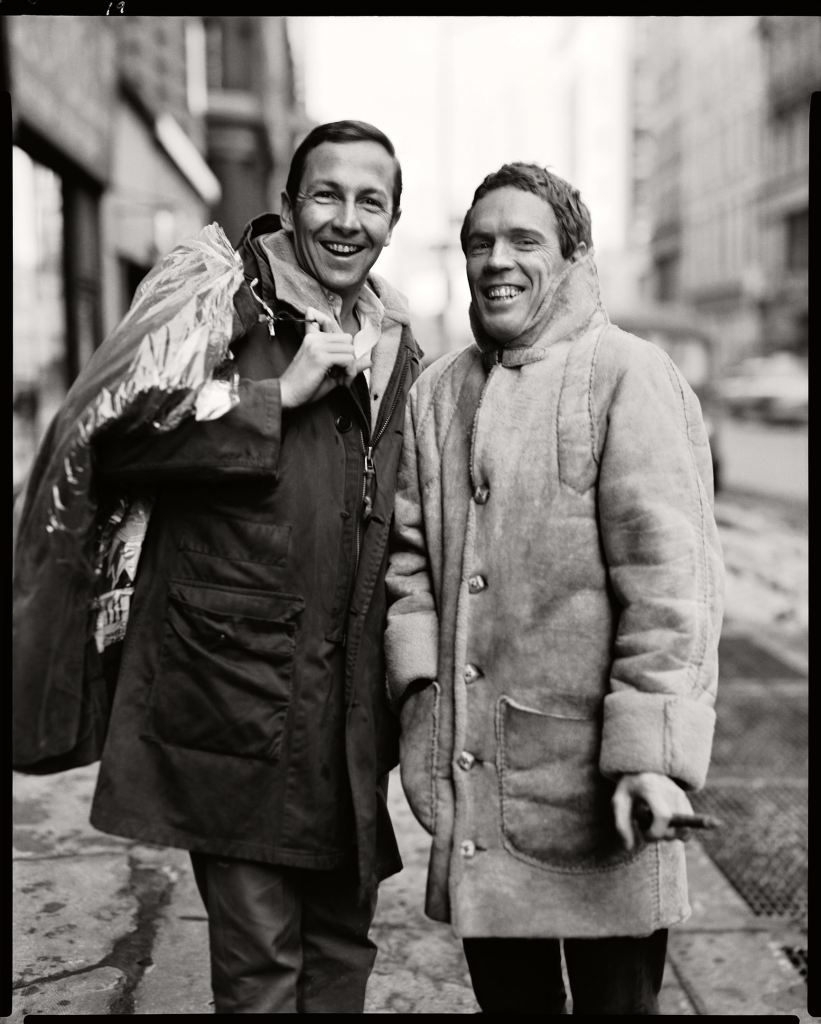

Alex Hay was a relatively little-known artist when he posed with his close friend and artistic collaborator Robert Rauschenberg for the above photo by Richard Avedon in January 1965.

Hay had moved to New York six years earlier, after finishing art school. But those who were aware of him mostly associated him with the performances he’d done as a member of the Judson Church circle. He’d only shown art in a single group show at Leo Castelli alongside Christo and Richard Artschwager.

Yet by 1971, after a series of solo shows at the Kornblee Gallery, Hay had built enough of a reputation that the New York Cultural Center organized a 50-work survey that drew the attention of critic Peter Schjeldahl, who called him a “gentle maverick” in his New York Times review.

“Hay is an odd case,” Schjeldahl wrote. His outsize sculptures of brown paper bags; his paintings of a cigar-box label and a sheet of legal paper; and the documents of his many performances with Rauschenberg and others made it practically impossible to categorize him. Pop art? Minimalism? Neo-Dada? Was Hay being coyly ironic? Or was he sincerely interested in paper airplanes and breakfast settings?

Hay seemed to be on the verge of something, cracking open a fissure between the dominant styles of the day with a strange and idiosyncratic approach. Yet just as critical momentum seemed to be gathering around him, Hay decided he’d had enough of the New York art world. By the early 1970s, he was living permanently in a small town called Bisbee, Arizona, near the Mexican border, where he quietly worked to renovate and repair a hotel into his private living space, fixing the roof and the plumbing and rewiring electrical circuits. He didn’t have another solo show in New York for 32 years.

Hay is now the subject of a career retrospective at Peter Freeman gallery (“Past Work and Cats, 1963–2020,” through May 29). It’s his sixth show with the dealer since 2003, when he began showing art again. On the occasion of the exhibition, we spoke with Hay about his early days with Rauschenberg, his new paintings of his cats, and why circumstances always determine everything.

Alex Hay’s retrospective at Peter Freeman includes the works he’s best known for, including three Paper Bag sculptures from 1968; his painting of a diner check (1966); a picture of a sheet of legal paper (1965); and a painting of a toaster (1968/2018). Note the tree emblem on the bag sculpture, which was what first drew the artist’s attention when he saw it in a shop. Photo courtesy the artist and Peter Freeman, Inc., New York. Photograph by Nicholas Knight Studio.

Why did you end up leaving New York permanently? Was it just not interesting anymore? Did you want to get away from art?

Well, I never had the idea that I was giving up art. I just saw what happens to an artist in New York. It changes you, being an artist and having some success. I saw it with all my friends.

But I loved New York. I got totally immersed in the art world. With Rauschenberg, he just liked to hang out around the kitchen table, which was a beautiful thing. So all of us would go down to Rauschenberg’s loft and it was a great time. But Bob never went to bars, he just sat around his table drinking Jack Daniel’s. He would basically drink a fifth of Jack Daniel’s every day. We all had the same doctor on Park Avenue and you’d just give him artwork and whatever you needed in terms of medical attention, he’d do for you. He didn’t understand why Rauschenberg didn’t have cirrhosis of the liver. And at that time, I got heavily involved in performance. Do you want that story?

I am interested in anything you want to tell me, Alex.

Okay. My wife at the time, Deborah Hay, who became a very well known choreographer and dancer, was taking classes with Merce Cunningham. He loved to have people come and watch his classes. So I did that. And at one point Bob and Judith Dunn—Judith was his principal dancer, and Bob was a composer and played piano—did a workshop using Cunningham’s theories, and it was such a turn on. After the workshop, we all went down to Judson Church and started doing performance work. I probably never would have done performance had it not been for that.

That’s where I met Rauschenberg because his partner, Steve Paxton, was at the workshop, and Rauschenberg came to see it. It was really one of those events in New York, where everyone who’s interested in new things that are happening would come to Judson to see our performances.

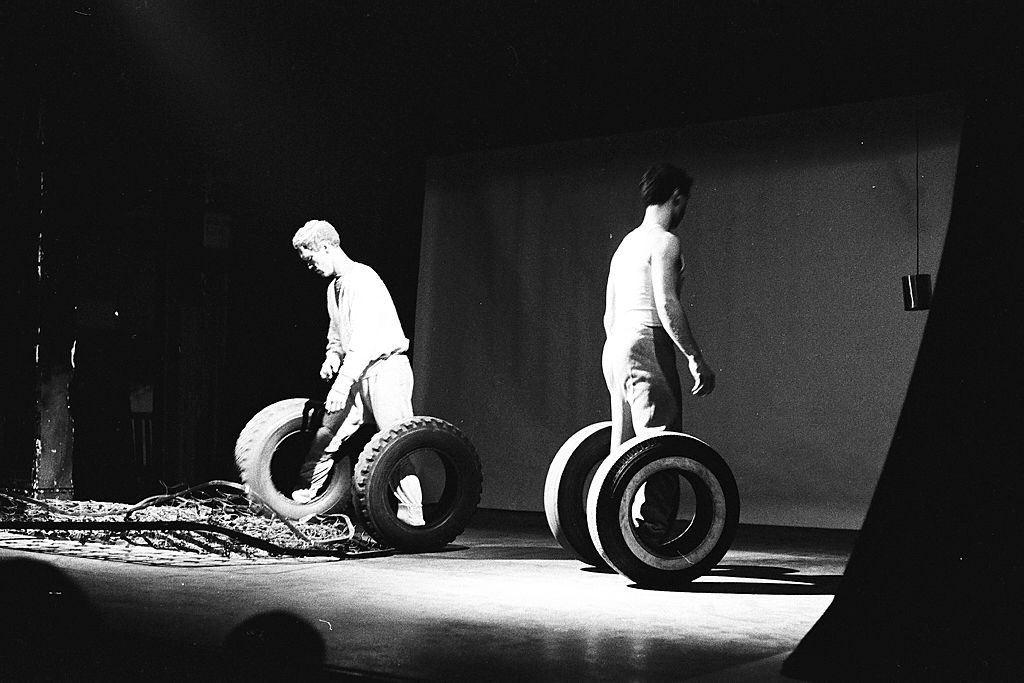

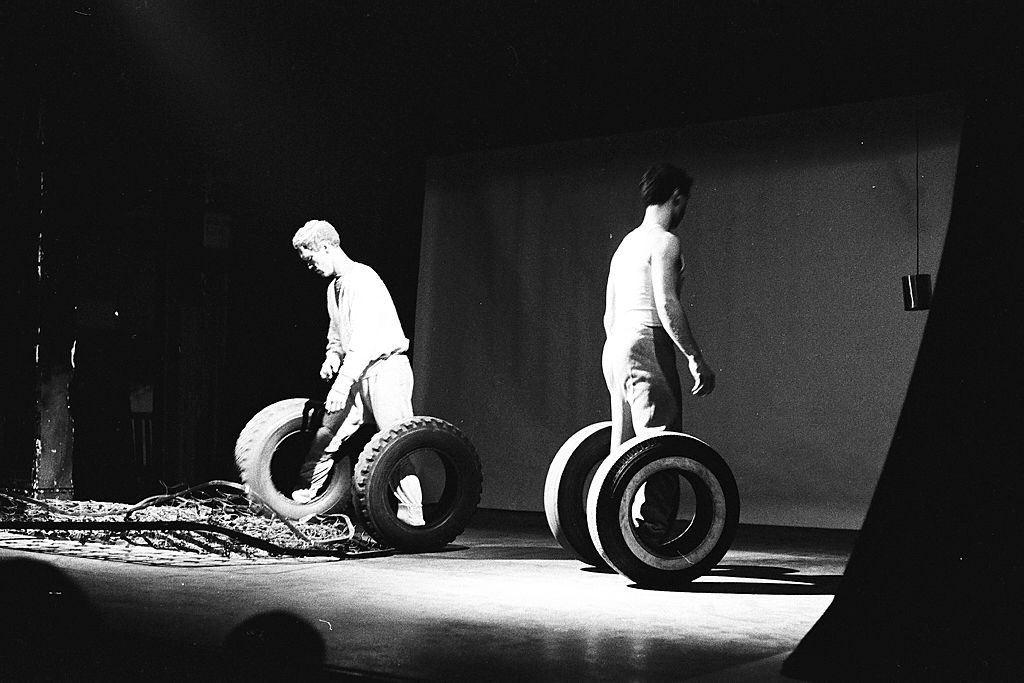

Alex Hay, on the left, with Steve Paxton in Robert Rauschenberg’s Map Room II. The performance took place in 1965 as part of the Expanded Cinema Festival, which also included pieces by Claes Oldenburg and Robert Whitman. Photo by Robert R. McElroy/Getty Images.

A critic once wrote that your visual artworks—giant sculptures of paper bags, cargo labels, pictures of receipts—often recreate things that look as if they’re about to be blown away. Do you see any connection between that kind of movement and performance?

I think that’s just what the critic saw. When I moved to New York, I wanted to do things that I had a very personal interest in, and I did not want to be overly influenced by other artists. With the bags, there was a guy who invented stand-up paper bags, and the bags his company made had a beautiful, printed little oak tree. And I admired that, this beautiful little emblem. It was very appealing to me. It didn’t have anything to do with things that can be blown away, although I can understand why he’s saying that.

That emblem, it seems like something you could easily miss.

Well, you know, if you want to make it so that it has a prominence, you made it large. That’s the reason for it. I didn’t want to make a small paper bag. I wanted to make a big paper bag.

In his paintings and sculptures, Alex Hay often reimagines paper products: receipts, sheets of legal paper, and cigar-box labels. The above work, Cargo Tag, was made in 1966. Photo courtesy the artist and Peter Freeman, Inc., New York. Photograph by Nicholas Knight Studio.

The press release for your Peter Freeman retrospective mentions that after you moved to Bisbee, Arizona, you developed an interest in esoteric subjects. Can you tell me a little about those? Did any of them make it into your work?

You know, it’s hard to answer a question like that because—well, for one thing, that was the time that Carlos Castaneda wrote his Don Juan books. Everyone was reading them. I was in Bisbee when they first came out. And at that time, I think everyone who was doing what I was doing—driving around the country—was interested in the Don Juan books.

What would you say you were looking for in those books?

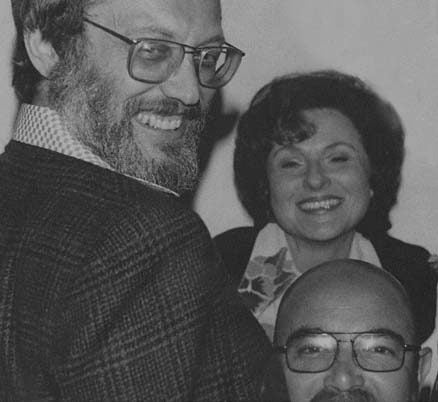

I had been coming out west to visit the Grinsteins [collectors Elyse and Stanley] in California every summer. I bought this old service truck and that’s what I would do, I’d drive around. And the freedom Carlos Castaneda was talking about in his books, I found that very, very intriguing.

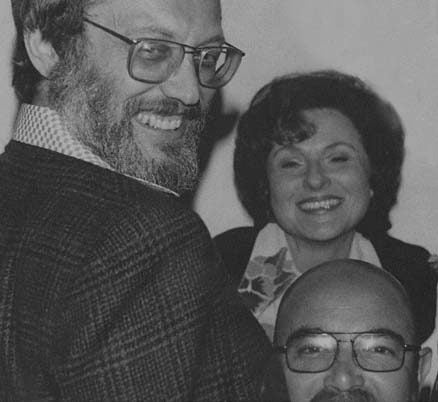

Stanley Grinstein and Elyse Grinstein with Sidney B. Felsen (at the bottom) in the 1960s. Hay was close with Stanley and Elyse, who invited the artist to California for several summers in the 1960s. Courtesy of Stanley and Elyse Grinstein, via the Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

What did you do once you got to Bisbee?

I took on a hotel, the Philadelphia Hotel, and the project I took to keep making things was to do everything that had to be done, whatever it was: floors, putting a roof on—I did a lot of work.

Did any of the skills you learned translate into later art projects?

To put it very simply, the circumstances were that I was working at the hotel. And while I was doing this, I saved little scraps of wood, and that was sort a personal collection. I had no idea what I was gonna do with these bits and pieces of wood.

How long were you saving them?

Oh, maybe five, six years. Something like that. So when I decided I would start making art again, I started using these scraps of wood. I wanted to make paintings of two-dimensional objects, so you could do a painting and be true to the nature of what you’re painting. You’re not trying to paint form because you’re dealing with two dimensions.

As he worked to renovate the Philadelphia Hotel in Bisbee, Arizona, into his private home and studio, Alex Hay collected scraps of wood that he depicted years later in paintings like the one above, which is titled Raw Wood (2004). Courtesy the artist and Peter Freeman, Inc., New York.

But were there any skills you learned while working on the hotel that translated into later art projects?

As an artist, I never bought a stretched canvas. I built everything myself. So those were the circumstances that gave me the skills to do the work I did on the hotel. Everything I did—and I can defend this statement very well—came out of some set of circumstances. This is my mode of operation. It’s what you would call the conceptual aspect of my work. Circumstances determined how certain possibilities presented themselves. That’s very important.

There’s an article by Peter Schjeldahl from 1971 in which he says you once spent two years making yourself a pair of boots. What were the circumstances of that?

I used to always buy boots from L.L. Bean. You know L.L. Bean? They used to make really beautiful hand-sewn boots. Then they stopped, so I decided, “Well, I’ll make my own boots.” So I carefully measured my foot in a very sort of complicated way to get the contour. And I built this tool that was basically a depth gauge out of wood so I could map out my foot. It took a hell of a long time.

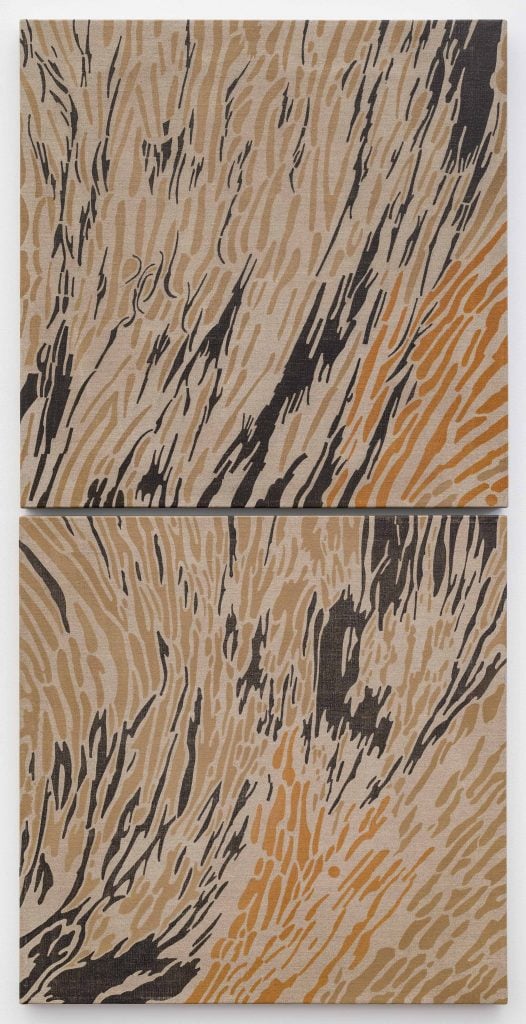

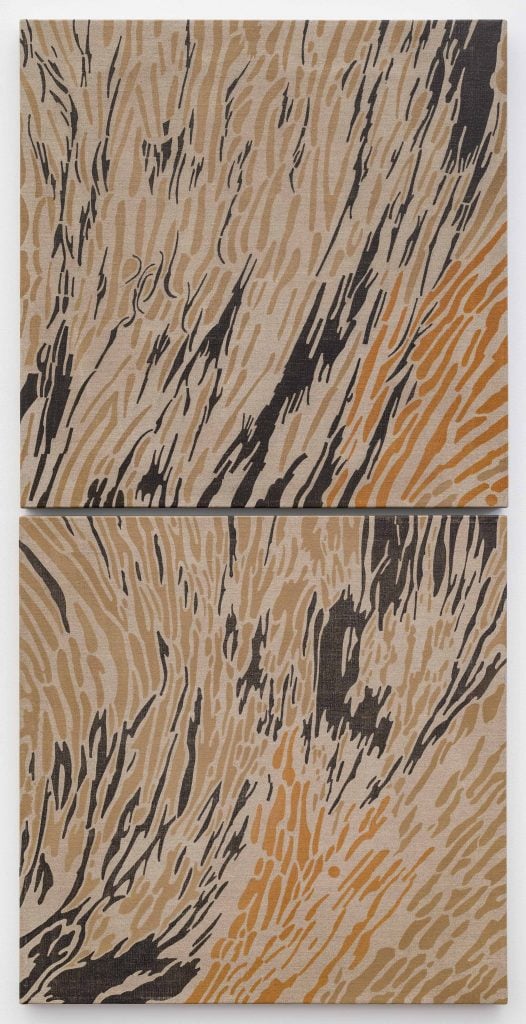

Your latest works in the Peter Freeman show are detailed paintings of the fur of four of your cats. What were you interested in there?

Well, if you have four cats, they’re a hell of a lot of work. You do everything for them. You have cats?

Alex Hay’s most recent works are four paintings based on his cats’ fur. The picture on the right is titled Lily (2019–20). In an earlier period in his career, Hay also made several chairs that he’s shown as artworks. The one on the left is from around 1970. Photo courtesy the artist and Peter Freeman, Inc., New York. Photograph by Nicholas Knight Studio.

I have two.

Then you know what I’m talking about. You have to feed them, you have to relate to them. We have a whole bunch of cats, four, maybe five. I had one downstairs that was quite old and I had to make a stool for it so it could jump up to the place where it ate. This is my orange tabby. And the stool I made has three legs instead of four, because with four-legged stools, it’s hard to get stability on uneven floor.

You’ve made and shown other chairs before as artworks. Would you do that with these stools?

You know, they’re very nice objects. Eventually I’ll make a couple and send them to Peter [Freeman] and he can have them in his gallery.

With the cat paintings, what convinced you to make them?

The circumstances were, if I have to do all this work to take care of these cats, why not use them for art?

What about the coloration?

I wasn’t trying to make a facsimile reproduction. There’s a painting of one cat, Bella, in two panels, that came closest. But basically, it was just patterns. The last painting I did was tortoise shell with black and a lot of canvas showing through and some bright orange color. But I wasn’t trying to duplicate colors. I just wanted to get the general details of the patterns.

Bella (2020) is another of Alex Hay’s recent cat paintings. Courtesy the artist and Peter Freeman, Inc., New York.

It’s been about 20 years now since you started showing art again after a long break. Do you feel like your earlier work, the things you made when you were still in New York, is being reassessed as a result of these past 20 years?

Are you asking me whether it’s happened, or what I think about it?

I don’t know—what’s the more interesting question?

Well you know, I never talked very much or publicized myself. So no, I don’t think anyone knows very much about what my life was like in New York.

But I think people would be quite interested to know, it seems to me. That’s why I called you.

Well, that’s basically the story.

Alex Hay in Bisbee, Arizona, where he has lived since the early 1970s. Courtesy the artist.

“Alex Hay: Past Work and Cats, 1963–2020” is on view at Peter Freeman in New York through May 29.