People

‘I’m a Huge Believer in the Gallery System’: Arts Patron Alia Al-Senussi on How Dealers Can Help Artists From the Arab World

We spoke with Al-Senussi about the rewards and challenges of promoting artists from the Middle East.

We spoke with Al-Senussi about the rewards and challenges of promoting artists from the Middle East.

Noor Brara

Few people in the art world advocate as much on the behalf of Middle Eastern artists as Princess Alia Al-Senussi, the scholar, curator, collector, and patron who is passionate about reconfiguring the cultural standing of international artists around the world.

Al-Senussi, who serves as a founding member of Tate’s acquisitions committee for the Middle East and North Africa and the UK and MENA Representative for Art Basel, as well as a board member for Art Dubai, the 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair, the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, and the Global Heritage Fund, has long spent her time trying to create opportunities for Arab artists to share their work and stories with a global audience.

Fresh off the opening of the Noor festival in Riyadh and the culmination of Art Dubai, Al-Senussi spoke to us about her passion for supporting and collecting, the art programming she’s excited about this year, and much more.

The last time we spoke, you told me how you fell in love with art while on a trip to Siwa with Emilia and Ilya Kabakov after completing your undergraduate degree. I’d love to get your thoughts on what art has done for you professionally and personally over the last year.

It’s more about the power of art as a community rather than individual works. Last year, to me, was about the centering of the art world’s community and learning to look at art as a form of relief and a form of hope. It was a really important moment to reflect on what the art world means to me and my friends and colleagues, and even people I don’t know all that well. And that last part is important, too, because when you see a work of art by an artist you wouldn’t know but you can immediately recognize, it’s comforting and it recalls community. You immediately recognize a Kusama—I don’t know Kusama well in a personal way, but I feel I know her, and I think that sense of familiarity with the artist’s work has been an absolute lifesaver to me. Art really came through for me in that sense.

How are you feeling now, as we come out of all this?

I actually felt that I needed to be there more for others. I think it was because I went through an incredibly difficult year of my own in 2016, in multiple ways, personally and professionally, with my PhD, Trump, and Brexit… things that I felt deeply affected me and how I felt the world saw me and how I saw the world. I had to lean on my friends and family in that time. So I think 2020 came at a time when I could be there for others and be their grounding point, and I was happy to do it.

Al-Senussi with her best friend, Dana Farouki, experiencing an artwork by Superflex in Tate’s Modern Turbine Hall. Photo courtesy Al-Senussi.

A lot of your work, especially right now, is geared towards promoting the work of Arab artists and Arab communities. You mentioned you were doing a series of moderated panels for the Noor festival in Riyadh and for Art Basel on these subjects. Why is this work important to you?

In general, I see one of the pillars of my work as normalizing Arab artists and artists of Arab origin.

For so long, there have been people who have worked to make artists from our ethnic backgrounds and our parts of the world just regular parts of the art conversation. It doesn’t have to be about these sad, marginalized communities, but rather viewing them as empowered, resilient communities that have existed in their own bubbles for a long time, that we should learn more about.

I feel very strongly about the Tate in that regard. Tate has been such an incredible organization that, yes, has these communities divided by different groups on their acquisitions committees—but at the same time, those committees bring in the work and those works are disseminated throughout the Tate community and collection. It’s incredibly important to make these conversations more fluid.

Are you optimistic that that kind of cohesion is going to increase over time?

Absolutely. Fifteen years ago, Saudi Arabia was an absolute pariah in the art world. So many wonderful, progressive people would just shut down the minute you mentioned Saudi artists. Now, people are much more open-minded.

Manal AlDowayan, Now You See Me, Now You Don’t installation view at Desert X AlUla, photo by Lance Gerber, courtesy the artist, RCU and Desert X.

Is there anything you wish other big art institutions like the Tate were doing more of? What are some ways people can start to normalize and bring together work from different communities?

One thing I hope we continue to do is travel. I know that was put on pause in 2020, and of course, we had large conversations about the climate emergency. Tate and many other institutions have talked about ways in which to decrease curatorial travel. I personally am not an advocate of that. I think there are many other ways to address the climate emergency and I think that travel is one of the most important ways in which we break down barriers. There is no way you’re going to understand what’s happening in another part of the world solely by Zoom.

I was just on a Zoom with a young curator in Saudi Arabia, and it was really important that I was on video with her. But it’s not the same as sitting in a museum cafe or Art Basel in the lounge and having that interaction. I just watched Mulan on the airplane, for God’s sake, and was thinking about how beautiful China looks, how I’ve loved my trips there. What better way to combat xenophobia and anti-Asian sentiment than to remember the wonderful trips I’ve had across Asia?

Definitely. Who are some Arab-world artists you’re excited about at the moment, who you feel people should know about?

Nasser Al Salem is someone I have seen develop over the years, and someone who embodies so much of the progress we have seen in the arts of the region. He dedicated himself to his work as an artist, but also played a variety of other art-world roles when there wasn’t yet a developed ecosystem. The culmination of all of this experience was his residency at the Delfina Foundation in 2019. The show that resulted was absolutely phenomenal in every way.

Basim Magdy’s work is witty, filled with absurd references and imbued with the aspiration we all have for a better future, even if we fail to get there.

Farah Al Qasimi’s work is a portrait of life in the Gulf states and of traditions of falconry, souqs, and of sprawling cities and domestic settings. Farah extrapolates issues of traditional gender roles in such an elegant way that the viewer has a more nuanced view of this place. Her work makes it seem not quite so far away, or like “the other.” Instead it looks more like “us.”

Farah Al Qasimi, Curtain Shop (2019). Courtesy of the artist.

What other initiatives are you working on or excited about this year?

I’m very pleased that the Noor festival is going on right now. I think the hunger for people to see art in real life is exciting. I’m not on Instagram, but I do understand the point of Instagrammable art and how it proliferates. Images are so wonderful, and I was able to share them with artists who couldn’t be there in person to see their works, like Carsten Höller and Emilia Kabakov, who was heartbroken she couldn’t go for her installation. I kept sending her pictures from friends and told her what they said about it and she was so touched. She was so excited to engage with the Saudi public in real life and even though she couldn’t do that, it’s been important for her to see people engage with her work.

The year has started off really well in terms of programming. Art Dubai was a wonderful moment for those in the UAE and those who traveled there. To have that interaction in the market with gallerists, even if they were doing virtual booths, was great. Coming up next, we have Art Basel Hong Kong and the Biennale in Riyadh, which is a project that’s been at the center of my life for the last two years. To have Phil Tinari, our curator and a dear friend who really understands this moment of change in Saudi, is great.

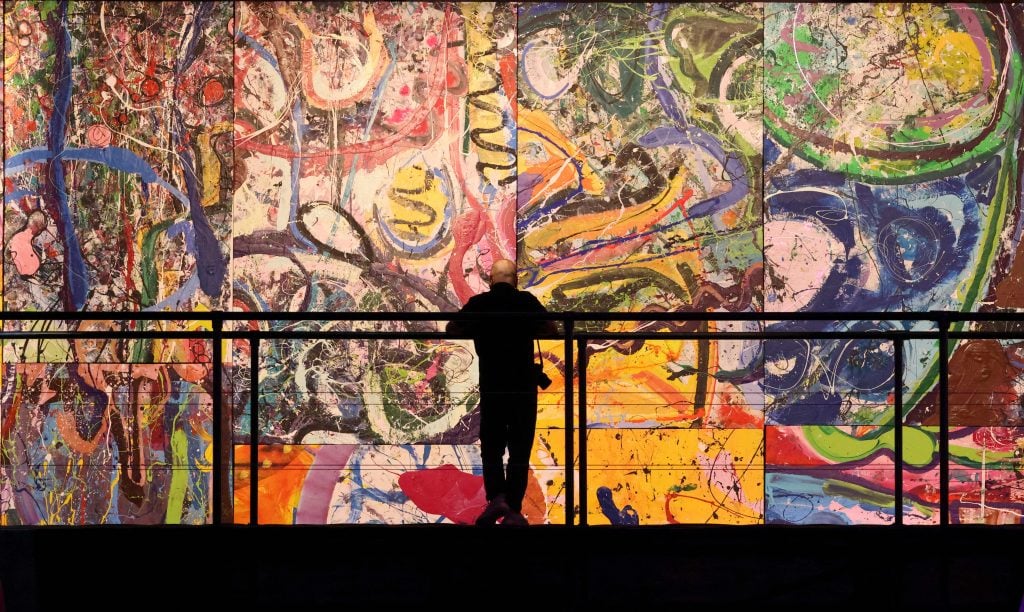

A visitor stares at fragments of Dubai-based British contemporary artist Sacha Jafri’s painting The Journey of Humanity, in the Emirati city of Dubai, on February 25, 2021. Photo by Karim Sahib/AFP via Getty Images.

I know this is something you try to stay away from, and we don’t want to stereotype or categorize artists from these regions, but in your work with Arab-world artists, have you noticed any similarities in terms of their approaches?

I’m a person of color in the United States—I’m half-Arab, half-American—and have always been really interested in this concept of the “other.” I remember being in university studying international relations and thinking about this “other” and how we make something of the other. That made me see that there are a lot of different art worlds. And I think what the established art world for so long tried to reject was anything that looked like craft, God forbid, or anything that looked almost raw. They rejected that completely as not intellectual or conceptual enough for a museum or an established gallery.

But what we’ve seen is communities using craft in a very intellectual way. I remember when I first started working with the Kabakovs in Siwa and in London with a lot of Middle Eastern artists, collectors would be like, “Oh, they’re so obsessed with politics. What about the concepts?” That’s all that mattered. Or, “What art school did they go to?”

I think when it comes to the Middle East, Western people think of it as all or nothing—either you reject your country completely and you become an activist against it, or you’re complicit in the state. That’s not correct. You can be a very proud patriot and still work within the system to try and change it. I think of Manal Aldowayan or Dana Awartani, two women of different generations who both talk about the role of women in society and push for women’s rights in a very elegant way that I think, frankly, made a difference. Those messages were translated to the powers that be and we see progress.

Is there anything you feel people can do to help promote the work Arab-world artists?

If you’re a collector, go and see if there’s anything you can add to your collection. That’s a really important message because people are still reticent to make that leap. I would love to see more gallerists engage with artists in the Arab art world. You rarely see that. I’m a huge believer in the gallery system, and as much as I think it’s wonderful that artists feel they can work on their own and don’t need it, I still think it’s important for an artist to have that person who is the interlocutor and mediator between them and the outside world.

Is there anything you want to end on?

I hope to see more young Arab artists engage with the artists in their communities. There are still not many collectors in the context of the Arab world. It’s different in the U.S. It’s still the largest art market in the world. I would love to see an entire community rise up in the Arab world and really embrace their artists however they can.