Reviews

Alice Neel’s Uptown Show Packs a Powerful Message

The artist spent several lean decades painting her Harlem neighbors, and the results are illuminating.

The artist spent several lean decades painting her Harlem neighbors, and the results are illuminating.

Christian Viveros-Fauné

At a time when the very idea of difference is under attack, it’s more important than ever to find voices that speak up for diversity. One such voice was the writer Jane Jacobs, who became known as urbanism’s poet laureate. Less known is the proposition that figurative artist Alice Neel was and remains America’s great painter of diversity—a fact clearly on view currently in a sparkling new show at David Zwirner gallery on 19th Street.

A 46-year resident of East Harlem and the Upper West Side from 1938 until her death in 1984, Neel spent several lean decades painting people who could not afford oil-on-canvas portraiture. These were her neighbors, their children, her friends and, just as often, cultural figures connected to Harlem or to the civil rights movement. Her subjects were also predominantly immigrant, black and Hispanic—the face of what sociologist Michael Harrington pegged, in his 1962 book, The Other America.

Now that the “other America” demographically resembles this country’s more ethnically diverse population, Neel’s portraits appear even more premonitory, representative and powerful.

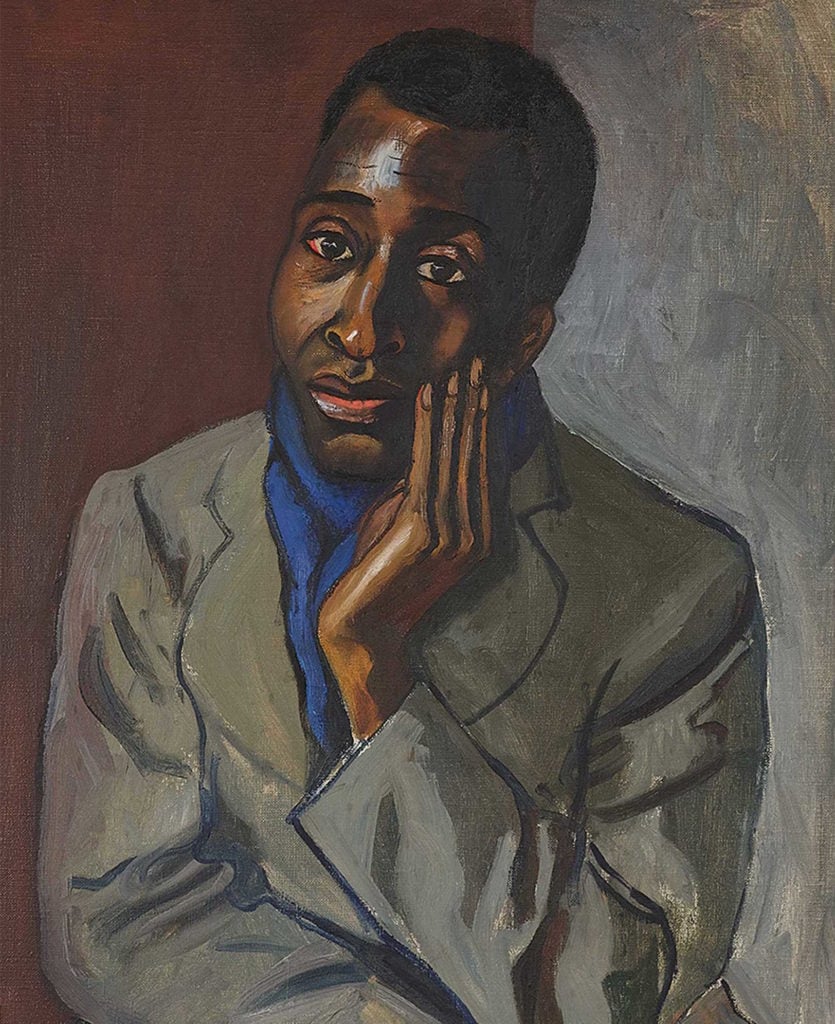

Alice Neel, Harold Cruse (c. 1950). © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London and Victoria Miro, London.

Enter Alice Neel, Uptown, a selection of paintings and works on paper plus related ephemera (it includes photographs as well as books and pamphlets authored by some of the artist’s subjects) organized by The New Yorker theater critic Hilton Als. An exhibition and an upcoming book (it is co-published by David Zwirner Books and Victoria Miro) that brings together Neel’s portraits of people of color for the first time, Als’ choices and commentary celebrate both Neel’s paintings and what the author calls “the generosity behind her seeing.”

Additionally identified in the book’s essays is the meanness of not a few liberal New Yorkers. After suggesting that Neel’s marginalization “by curators like Henry Geldzahler” was inspired by “the fact that she painted different people,” the critic goes on to blowtorch the white establishment’s narcissistic prejudices.

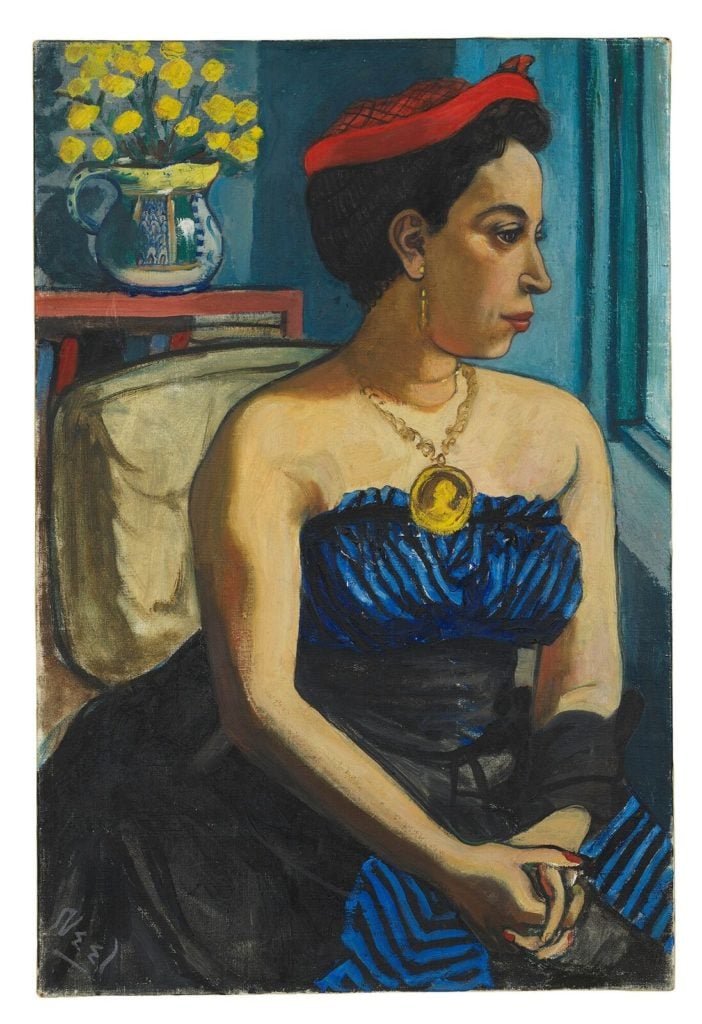

Alice Neel, Alice Childress (1950). Collection of Art Berliner. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London and Victoria Miro, London.

“Had Neel restricted her canvas to the white world,” Als writes, “she would have been celebrated sooner, swear to God, because then her detractors, or the people who ignored or marginalized her, would have seen themselves, which, in the art world is always rewarded.”

Were singer Elvis Costello quizzed today on similarly blasé resistance to Neel’s portraits he would probably add: “What’s so funny about peace, love and understanding?”

Those sentiments—or at least the kind of empathy that Neel channels in every one of her stirring portraits—are, in Als’ formulation, the bedrock undergirding both the book and the exhibition. “What fascinated her was the breadth of humanity that she encountered,” Als writes about the period the artist spent living in Spanish Harlem. Elsewhere, Als brilliantly tags Neel’s principal theme as “diversity not calling attention to itself.” Both statements effectively counter another comfortable liberal prejudice: the art world’s preference for poker-faced conceptualism over dry-eyed depictions like Neel’s.

Though she mostly lived and worked in near obscurity above 107th Street, Neel was as committed to capturing her sitters’ character as the era’s most engagé documentary photographer. “I paint my time using the people as evidence,” she wrote in a 1964 artist’s statement. No wonder, then, that she chose to portray some well-known figures alongside less recognizable folks. Among them are the playwright, actress, and author Alice Childress; the sociologist Horace R. Cayton, Jr.; the community activist Mercedes Arroyo; the academic Harold Cruse; and the civil rights activist James Farmer. As represented by Neel, each embodies the basic human paradox of being both unique and typical.

Take, for instance, Neel’s 1950 portrait of Childress: a picture of Harlem royalty, it depicts the light-skinned artist dressed in a blue frock with a red hat atop her head that resembles a crown. The fact that Childress stares resolutely out the window—most of Neel’s portraits face forward and focus diligently on the eyes—invites thoughts that the artistic polymath was scanning for Benjie, the 13-year-old heroin addict she immortalized in her 1970 novel A Hero Ain’t Nothin’ But a Sandwich.

A second picture of the writer Harold Cruse also appears to have significantly anticipated its subject’s future. A circa 1950 portrait of a pensive intellectual with fretting hands, the artwork antedates the author’s 1967 opera prima, The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual.

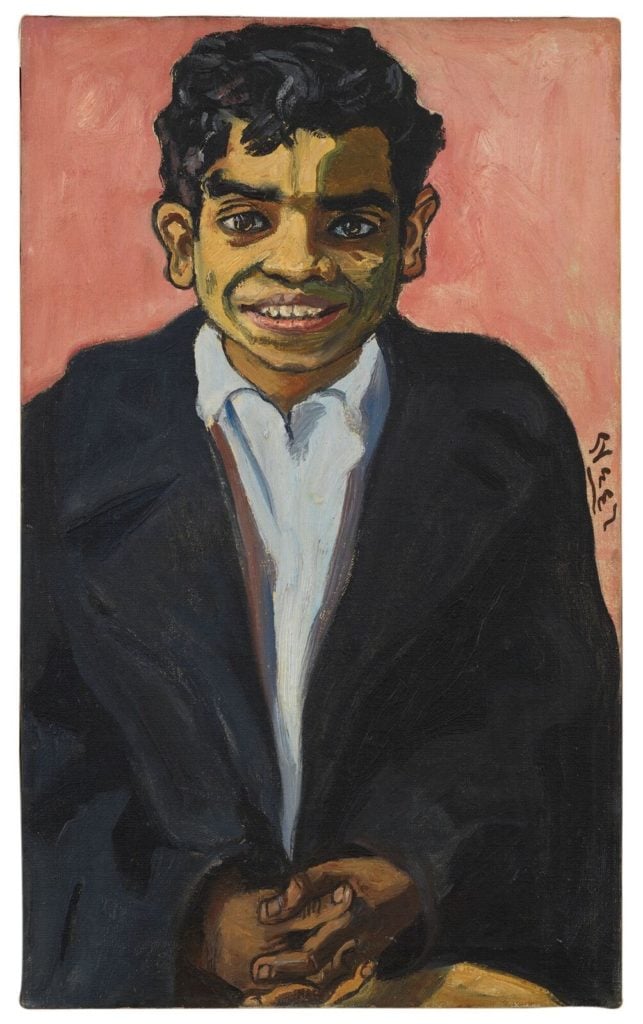

Alice Neel, Georgie Arce (1955). Collection of William T. Hillman. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London and Victoria Miro, London.

An argument can be made that Neel reserved her best, most perceptive nose for difference for her less known sitters. The 1954 ink and gouache drawing Two Girls, for example, depicts two schoolgirls—one black, the other brown—embracing on a sofa. Together they embody what Als calls “diversity within diversity.” With Carmen and Judy, from 1972, Neel clearly imbued some of her own hard-knock life into a picture of a breast-feeding mother and her developmentally disabled daughter. Like Carmen, a Haitian immigrant, Neel also lost a child and lived for years on poverty’s razor’s edge.

But few pictures in either the book or exhibition match the paintings and drawings Neel made of young Georgie Arce, a neighborhood errand boy, between the years 1950 and 1959. They range from a jaunty painting of Georgie posing with one laceless boot propped on a rattan chair to a seated portrait in which he is depicted as a movie thug holding a buck knife. What Neel captures expertly is her sitter’s antic self-dramatization—the pictures prefigure street cultures like narcocorridos and gansta rap. In 1974, 15 years after Neel painted her last portrait of Georgie Arce, he was convicted of murder and sentenced to 25 years at a correctional facility in Auburn, New York.

These pictures and others are not only unmarred by agendas of any kind, they appear instead to have been created out of a profound need to understand what lies beyond their sitters’ social standing and self-presentations. This, among other leaps of sympathetic intelligence, makes Neel’s portraits resemble collaborations—they render difference recognizable and uniqueness special.

“In our American cities, we need all kinds of diversity, intricately mingled in mutual support,” Jacobs wrote in The Death and Life of Great American Cities. “We need this so city life can work decently and constructively, and so the people of cities can sustain (and further develop) their society and civilization.”

On the evidence of this unmissable exhibition and compelling book, it’s clear that few American artists answered the call to celebrate difference as early or as uncompromisingly as Alice Neel.