Chicago-based artist Michelle Hartney has produced an alternate audio guide to correct what she says was the historical reality of the prostitute women depicted in the Art Institute of Chicago’s show on Ukiyo-e paintings from the Roger Weston collection. On Sunday, the artist and some of her collaborators staged a protest at the museum where they played her guide in the galleries.

“They need to be presenting more information on what was going on with these women in these paintings,” Hartney tells artnet News. “A small iPad in the corner of the show glazed over their living conditions, but didn’t go into how these women were beaten, kept in boxes, and starved.”

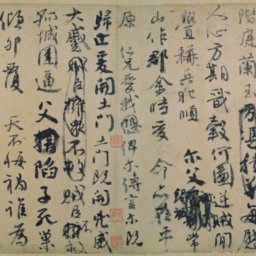

In 17th-century Japan, cities such as Kyoto, Osaka, and Edo (now Tokyo) included busy entertainment districts known as ukiyo (or “floating cities”) filled with brothels, theaters, and seasonal festivities. Artists were commissioned to capture the people in these places in paintings known as ukiyo-e, or “pictures from the floating world,” in a number of mediums ranging from folding screens, hanging scrolls, and hand scrolls, to albums or single sheets.

Kaigetsudō Doshu,Standing Courtesan Wearing a Kimono with a Pattern of Clematis Flowers (1789-1801). Photo courtesy of the Weston Collection and the Art Institute of Chicago.

One of the most popular themes in these works were bijin (or beauties), which typically depicted prostitutes, geisha, actresses, or other fashionable women who embodied the era’s ideals of beauty and style.

However, Hartney says the exhibition at the Art Institute fails to properly contextualize the realities facing the women depicted in the drawings on view. In her audio guide, which visitors can access on Soundcloud, the artist reveals that most of the women in the entertainment districts were sold into prostitution by their families as teenagers and were bound to restrictive indentured contracts for up to a decade in order to pay back the money their parents received up-front from the brothel owners.

Conditions were horrendous, and prostitutes endured unthinkable cruelty. The women were frequently beaten by brothel owners, malnourished, and often suffered from debilitating sexually-transmitted diseases. There are even records of women being housed in cages or boxes when they weren’t seeing customers.

All of this crucial information is omitted from the Art Institute’s exhibition, Hartney says. “I believe that museums are purposely withholding a lot of information,” she says. “A big part of it is the power dynamics that exist between people in charge of museums and the donors that help these museums run. Sexism and racism infiltrates decisions that are made about what is presented and how it’s presented. It’s a really easy fix. You have the information, so just tell us. It’s impossible for me to think they didn’t know this information.”