On View

What Amy Sherald Is Looking At: The Painter on 8 Cultural Touchstones That Inspire Her, From Wes Anderson to WEB Du Bois

See the influences behind the artist's debut show at Hauser & Wirth in New York.

See the influences behind the artist's debut show at Hauser & Wirth in New York.

Sarah Cascone

Given the headlines Amy Sherald made last year with her official portrait of former First Lady Michelle Obama, one might be surprised to learn that her debut exhibition at Hauser and Wirth, which opened in New York this week, is her first solo show in the city.

“I purposely skipped the New York scene,” Sherald told artnet News. “If I was going to have a show in New York, I wanted it to be a show like this, not just at a random art space.”

The show features eight new paintings, all but one of which were completed this year. With two canvases measuring at least 10 feet tall, this body of work sees Sherald working at a larger scale than ever before. But you’ll still spot the immediately identifiable trademarks of her work: Colorfully clad black men and women posed against a vivid, single-hue backdrop, their skin rendered in gray-scale. (Sherald plucks her models off the street when they catch her eye, and she often outfits themselves in clothes she’s purchased for that purpose.)

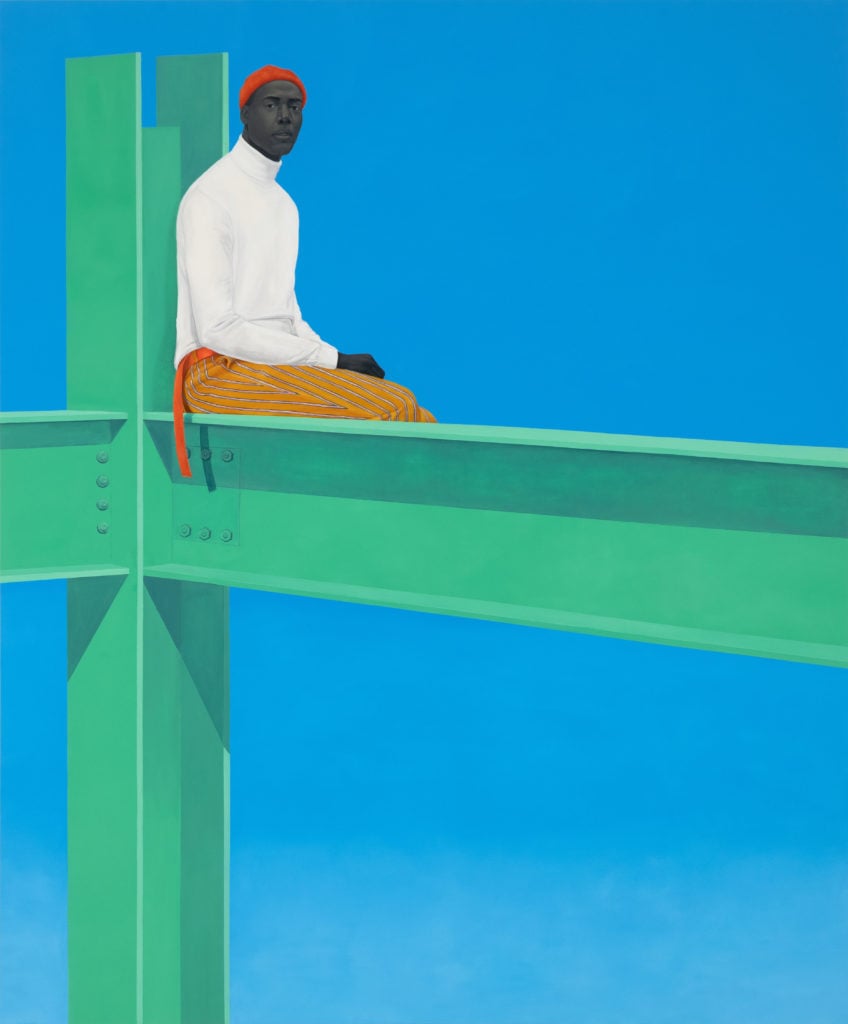

Sherald grew up spending summers with family in Panama, where each room in the house was painted a different color. In the two monumental works in the show, she’s evolved beyond her highly-saturated monochromatic grounds to feature fully realized scenes. In one, the figures stand on a beach; in the other perched on a steel girder. (The latter is inspired by Charles Ebbets’s famous 1932 photograph of workers sitting on a construction beam high over Rockefeller Center eating their lunches.)

Amy Sherald, If you surrendered to the air you could ride it (2019). Photo by Joseph Hyde, ©Amy Sherald, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

And over the past year or so, Sherald’s ideas about what she hopes to do in her work—to represent African Americans through the lens of “interior space and our own private identity”—have crystallized.

Some of her influences have stayed with her for many years, such as Bo Bartlett’s 1986 canvas Object Permanence, which Sherald considers “the first real painting I ever saw in my whole life.”

Amy Sherald, Precious jewels by the sea (2019). Photo by Joseph Hyde, ©Amy Sherald, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

She’s also been doing a lot of reading, and has found that writers including Elizabeth Alexander and Kevin Quashie had articulated in words many of the themes she was hoping to communicate in the paintings.

Ahead of this week’s opening, we spoke with Sherald about the cultural touchstones that have fueled her latest paintings—all of which have already sold, by the way—and what ties them together.

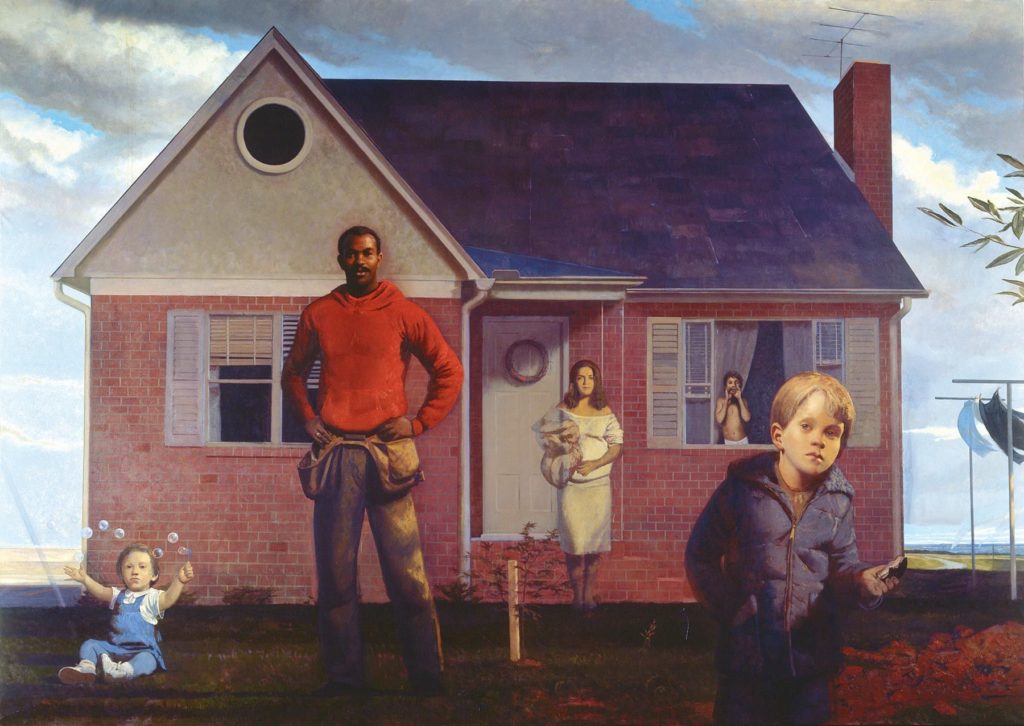

Bo Bartlett, Object Permanence (1986). Courtesy of the artist.

Sherald first saw this painting, in which Bartlett, a white man, depicts himself as African American, on a sixth-grade field trip. “The image of a young black man looking at me, just seeing myself in that work was powerful,” she said. “I still feel the same about it and it’s still a great part of my inspiration as a figurative painter. It’s a reminder that there need to be more images out there existing in the world that can offer other children and people that same experience that I had in that moment when I first saw that painting in a museum.”

The artist only realized that Bartlett was white a few years ago, but “that made it more interesting to me,” she said. “I grew up loving Reese Witherspoon movies. I was able to look at her and internalize who she was. But I don’t think people for the most part look at black people and see themselves. When a white cop sees a young white teenager, he sees his son. He won’t look at a young black teenager and see the same thing. For Bo to imagine himself into that body is essentially what brings humanity together, what brings empathy to and humanizes the black experience.”

Ewan McGregor in Tim Burton’s Big Fish. Film still courtesy of Columbia Pictures.

A few years after Tim Burton’s film Big Fish appeared in theaters, Sherald checked the film out of the library. “It was maybe in 2007, it was a year where I was trying to figure out what kind of work I wanted to make, and what I wanted to bring to the conversation and the art historical narrative,” she recalled. “In the film, watching this father tell his son all of these stories about his life and his experiences, I realized he had the freedom to see himself any way he wanted to—in a magical way.”

“I realized that the paintings I wanted to make were the paintings that I wanted to see in the world,” Sherald said. “There’s a way of being that you don’t see in art history when it comes to the black figure. The body is always relegated to political action. The public identity of a black person is what becomes, as opposed to who we are in our interior experiences. But I realized that as a figurative painter, I have the power to create these archetypes that can critique art-historical narratives and offer people a reflection of themselves.”

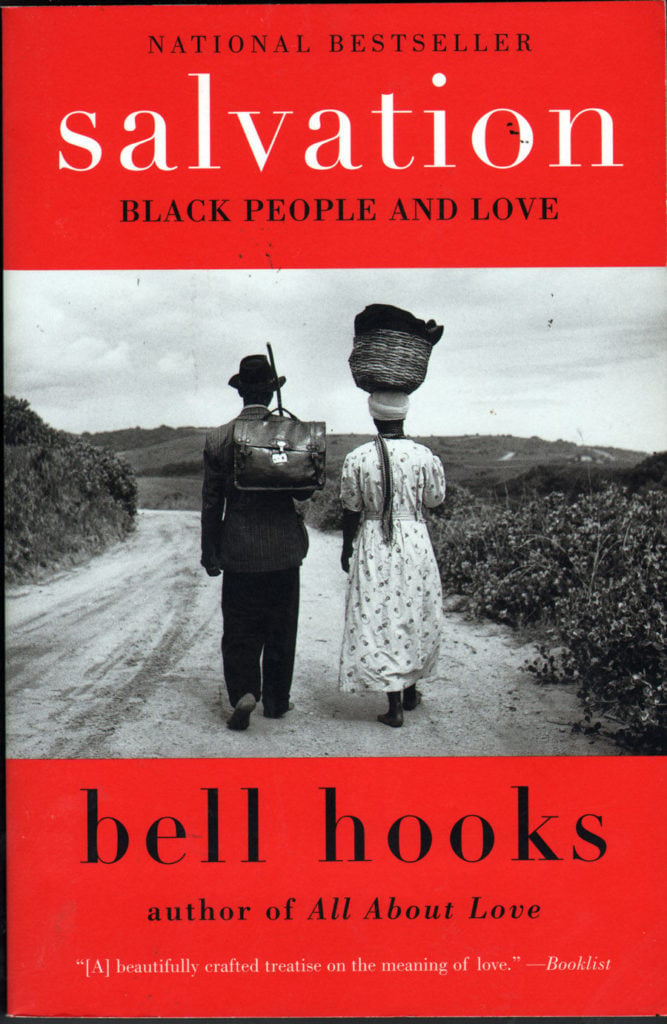

Salvation: Black People and Love by bell hooks (2001). Courtesy of Harper Perennial.

For the past year, as Sherald was at work on the show, she was reading Salvation. She borrowed the exhibition title, “The Heart of the Matter,” from the first chapter because, she said, “I feel like my work gets down to the heart of matter of what it means to be us in the world and the everyday reality. That chapter speaks about a love ethic and getting back into loving yourself. That’s a very rudimentary way to describe it.”

This photo was included in “American Negro,” presented by WEB Du Bois at the 1900 Paris Exhibition. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, DC.

When Sherald began her research about depictions of black people throughout art history, she was immediately taken by the photographs of African Americans that WEB Du Bois presented at the Paris Exhibition in 1900. “They were there to counter racist propaganda; to say ‘this is who we really are.’ For a long time, we couldn’t control that narrative, but after the invention of the camera, we could become authors of our own narrative,” she said. “When I saw these photos, it was affirmation that I was headed in the right direction. The show was about the expression of our own humanity and a counter narrative.”

There’s also a purely visual connection between these historic images and Sherald’s work, she added: “I’m painting the figures in gray, and these beautiful photographs are in gray.”

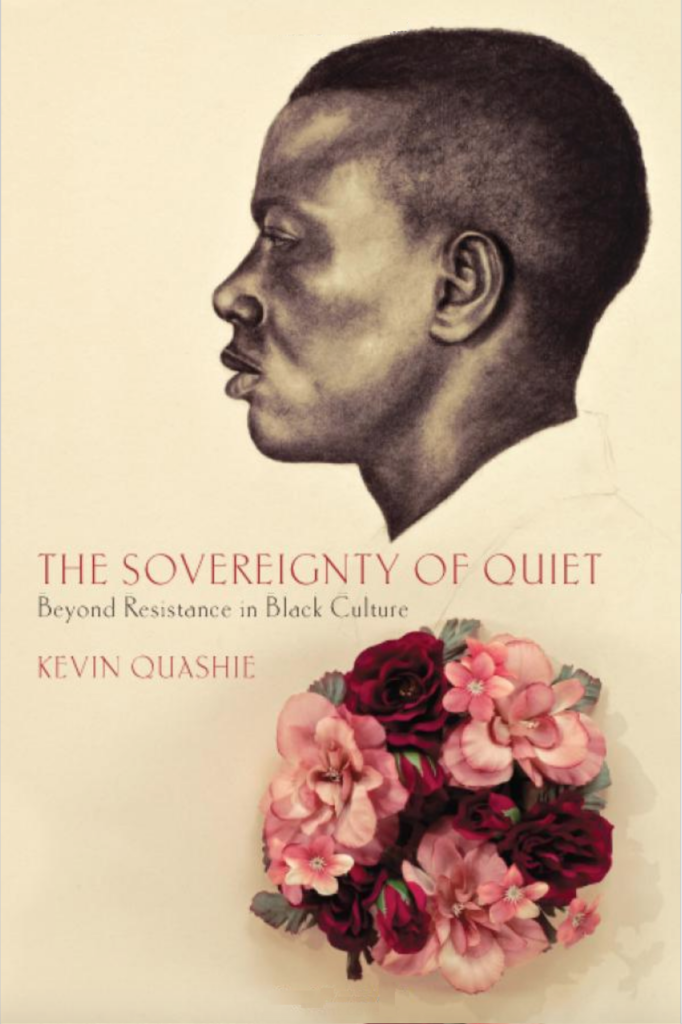

The Sovereignty of Quiet: Beyond Resistance in Black Culture by Kevin Quashie (2012). Courtesy of Rutgers University Press.

“Kevin wrote about the feelings that I want people to leave with when they look at the work,” Sherald said. “They’re quiet and they’re about going into yourself as a form of resistance. In the African American narrative from slavery to now, it’s about resisting and overcoming and about getting to a place of equality.”

“I did a talk at Spellman College in Atlanta, and the woman I was speaking with said, ‘the way that you’re speaking about your work is the way that this author wrote in his book,” Sherald added. “I was like, ‘this is exactly what I’m trying to say, except he says it better.’ I speak visually and he’s a writer, so he clarified it for me.”

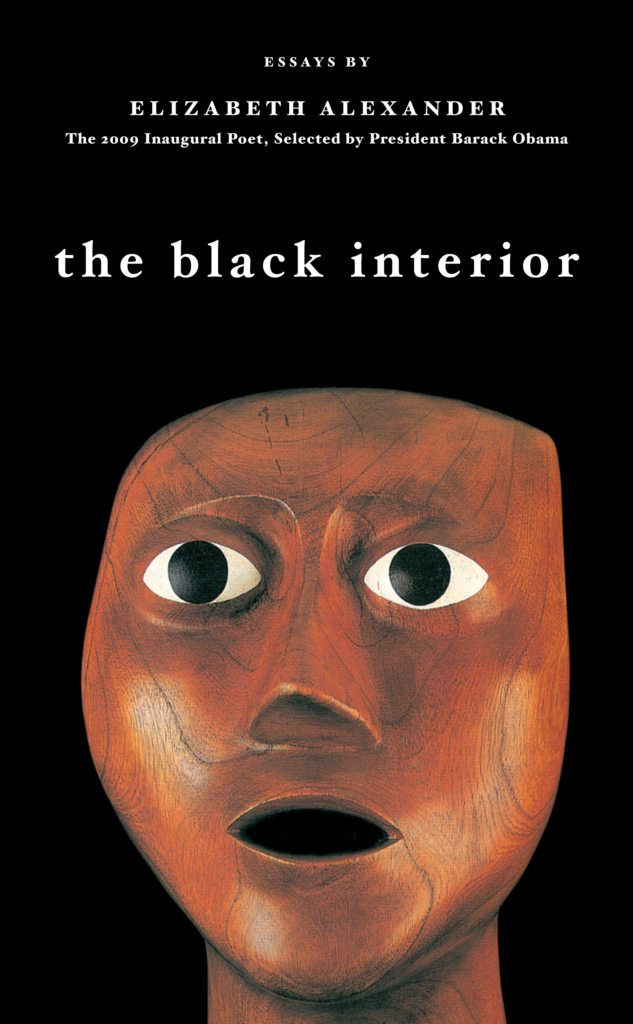

The Black Interior: Essays by Elizabeth Alexander. Courtesy of Graywolf Press.

“I am interested in an exploration of a more private identity of blackness versus a more public identity,” said Sherald. “This is another book that clarified what my work was doing. It’s our truth is being represented visually and becoming a part of the American art canon.”

Kara Hayward in Wes Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom. Film still courtesy of Focus Features.

“I’m a big fan of Wes Anderson, his palette, his dressing style, how he frames his scenes,” said Sherald. “I watch his movies and pause them and say ‘that would be a beautiful painting, and this would be a beautiful painting, and this would be a beautiful painting!'” She named the scene where Suzy Bishop, one of the two main characters in the coming-of-age film Moonrise Kingdom, stands atop a lighthouse tower looking through the binoculars out over the water, as a particular favorite.

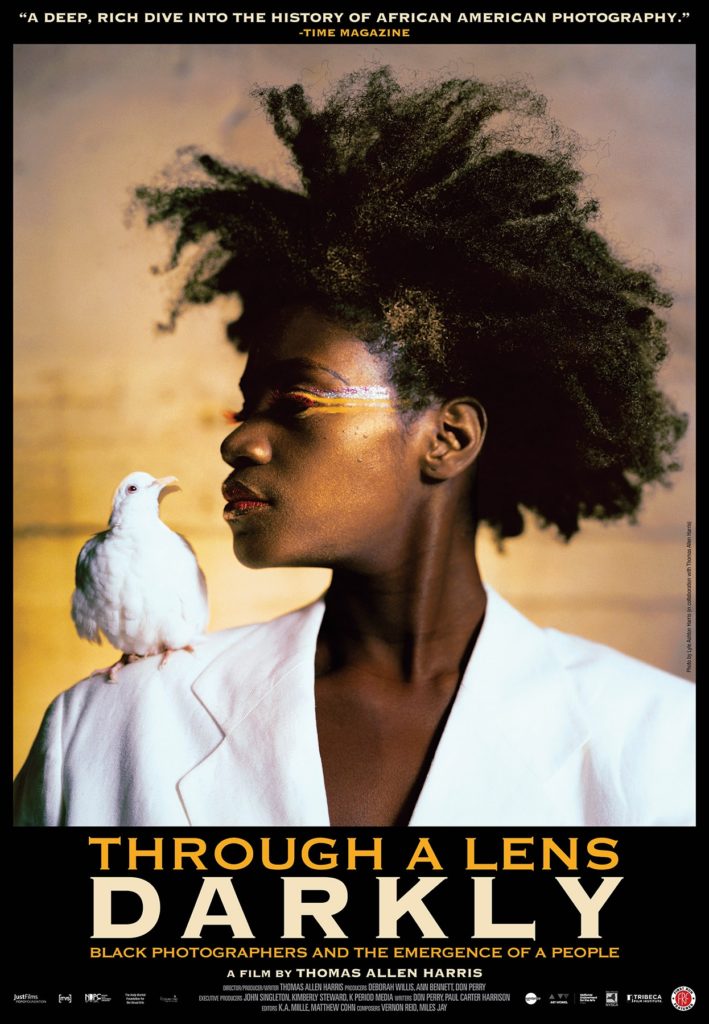

Thomas Allen Harris, Through a Lens Darkly: Black Photographers and the Emergence of a People (2014). Courtesy of Chimpanzee Productions.

With her busy schedule, Sherald rarely makes time to go to the theater, but a friend who works at Philadelphia’s BlackStar Film Festival once loaned her this documentary produced by photographer Deborah Willis.

“The documentary is about how the camera was put into use by African Americans,” said Sherald. “Frederick Douglass was the most photographed person of his time, more than [Abraham] Lincoln. He saw the camera as a tool to do work—having images out there that represented the humanity of black people was the most powerful thing we could do.”

“Amy Sherald the heart of the matter…” is on view at Hauser & Wirth, 548 West 22nd Street, New York, September 10–October 26, 2019.