Art & Exhibitions

Anaïs Nin’s Never-Before-Seen Paintings and Personal Artifacts Get an Outing in L.A.

"Celebrating a Renegade" explores the godmother of erotica's polarizing legacy.

Rare treasures from the life of literary legend Anaïs Nin went on view in Santa Monica this week. The famed diarist was born in France, raised in New York, and returned to Paris before moving to America permanently in the 1930s. She spent a significant amount of time in LA along the way. Her ashes were scattered in Santa Monica Bay.

Elizabeth Banks’s Brownstone Productions collaborated with the Anaïs Nin Foundation on “Celebrating a Renegade,” a multigenerational exhibition that shares ephemera, artworks Nin made, paintings made of her, and pieces from five contemporary artists inspired by her legacy. The Georgian Hotel’s creative director Amber Arbucci curated the show, which remains on view at the landmark hotel’s Gallery 33 through March 22.

An installation featuring Nin’s typewriter, and three portraits pulled from her Silver Lake home—two of which are by John Maynard. Photo: Dashiell King, courtesy of The Georgian Hotel

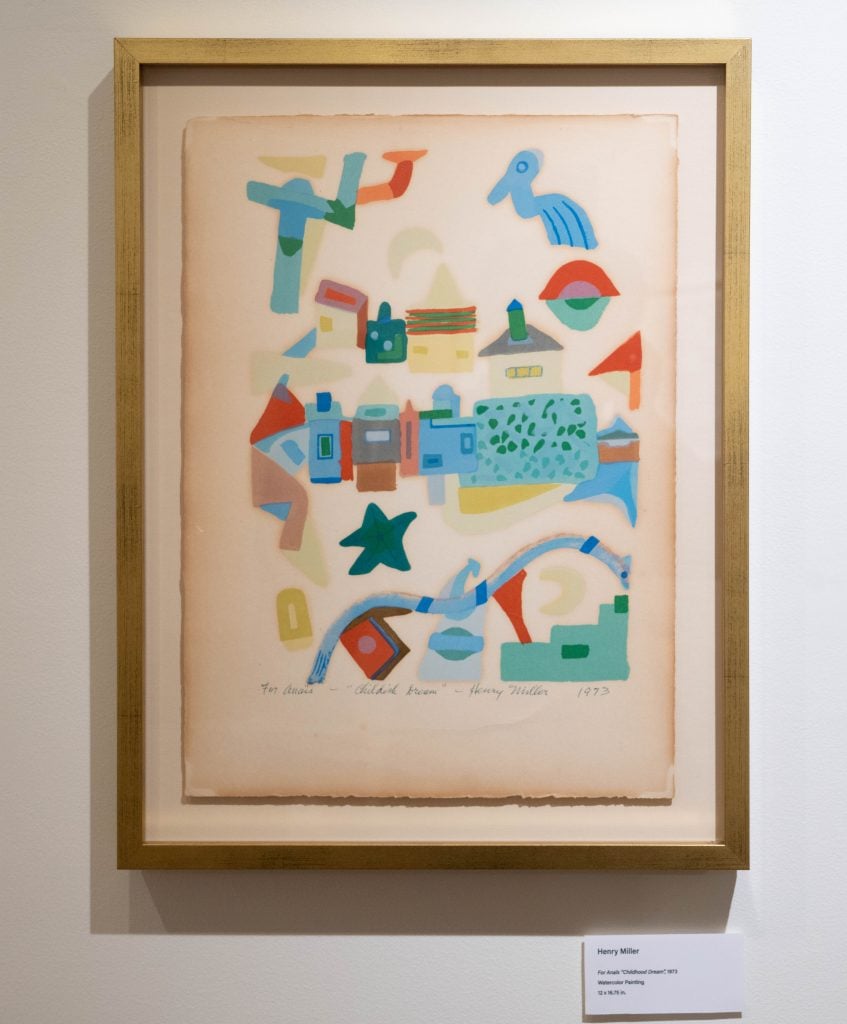

Exhibition producer Brandon Milbradt told me she pitched this concept to the Georgian while developing a TV series around Nin. “Anaïs deeply admired artists, was a champion of other creators,” Milbrandt wrote. “I thought, why not showcase Anaïs with artists inspired by Nin herself?” Throughout her life, Nin produced four novels, four works of nonfiction, five collections of short stories, and kept a diary for 63 years that detailed her poetic introspections and many torrid affairs. Never-before-seen watercolors that famed author Henry Miller painted for Nin appear in “Celebrating a Renegade.”

Henry Miller, Childhood Dream (1973). Photo: Dashiell King, courtesy of The Georgian Hotel

“Anaïs was a dangerous writer in her time, and, for better or worse, is just as relevant today,” Milbradt said. In the 47 years since Nin’s death, she’s been called a monster (because she terminated a pregnancy), a narcissist (because she liked ostentatious outfits), and a bigamist (because she was.) But, as Nin’s diary noted, “no one has ever loved an adventurous woman as they have loved adventurous men.”

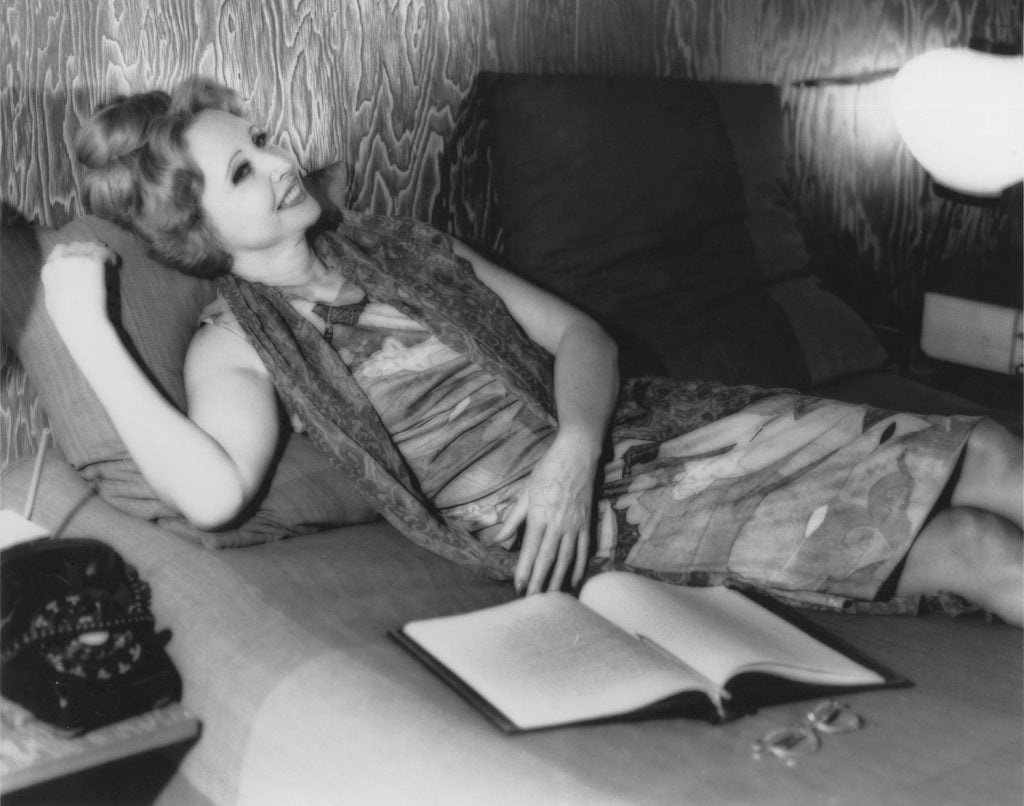

Anaïs Nin. Courtesy of the Anaïs Nin Foundation

Nin was born in 1903 to two musicians. Nin’s mother moved her and her two brothers to New York after her father absconded with his mistress. Nin’s diary began as a letter entreating her father to return on that very voyage, at age 11. She dropped out of high school to work as an artist’s model and met her first husband, banker Hugh Guiler, in Havana at 20. Guiler elected to be omitted from the seven volumes of Nin’s diary that she edited and published from 1966 through 1977, but they stayed together throughout Nin’s life. Guiler’s money helped support the bohemians she knew.

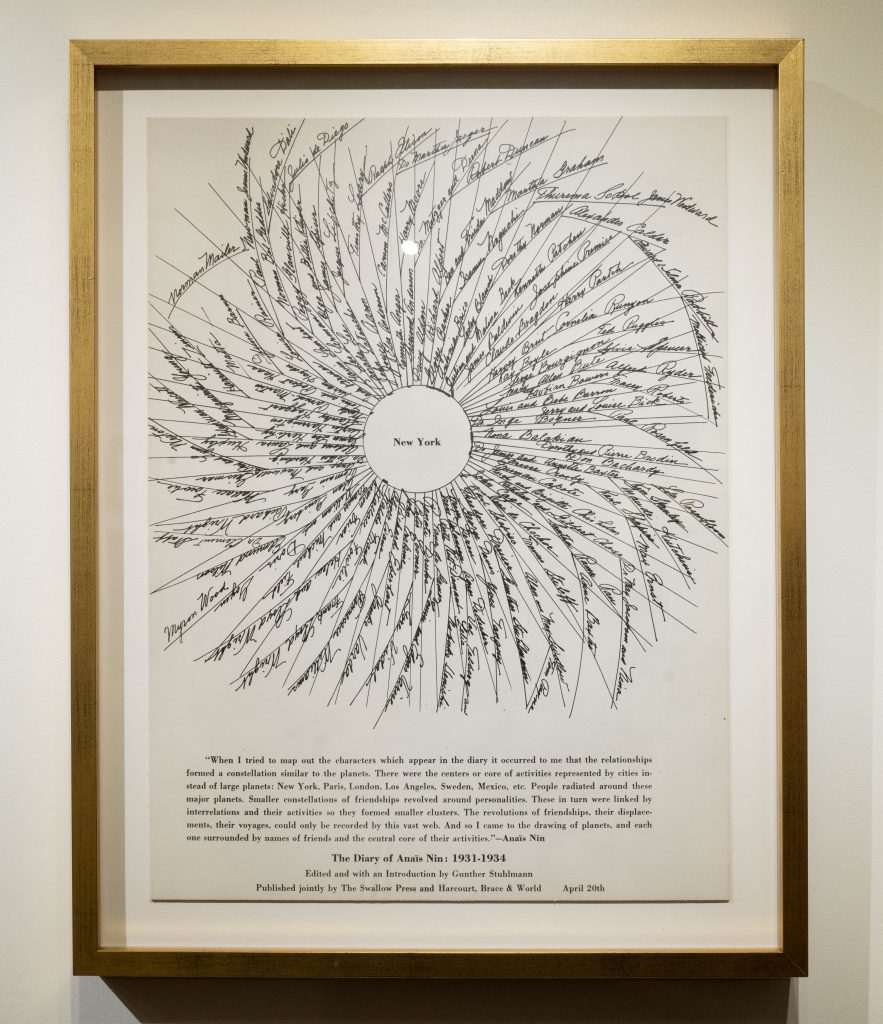

Anaïs Nin, Circle of Friends, New York. Photo by Dashiell King. courtesy of The Georgian Hotel

“You are always asked to solve problems, to help, to be selfless,” Miller is recorded as telling Nin in a 1932 diary entry. “Meanwhile there is your writing, deeper and better than anybody’s, which nobody gives a damn about and nobody helps you to do.” Readers did give a damn about Nin’s writing though, ever since her diary debuted at the height of feminism’s second wave—and despite a period of repudiation when her ex-husband published her unedited diaries and extensive erotica.

Henry Miller, For Anaïs from Henry (1979). Photo by Dashiell King. courtesy of The Georgian Hotel

No amount of moralizing ever extinguished Nin’s impact. Social media and sex positivity have reinstated her accolades.

“Celebrating a Renegade” hangs Nin’s rarely-seen Circle of Friends drawings next to a contemporary collage with her face at center by Colette Standish, who produced an entire series of treated mirrors and lightboxes titled “Anaïs Through the Looking Glass and Other Stories.” The nudes of Michelle Magdalena Maddox’s sensual black-and-white photographs evoke Nin in more ways than one. Javiera Estrada’s technicolor free love photography also appears, alongside an intimate bathtub scene painted by Chloe Strang. Elsewhere, fragments from Amanda Maciel Antunes’s Trapeze Project foreground Nin’s relics.

An installation featuring Anaïs Nin’s diaries, old photos, and a handwritten note from Henry Miller on vintage Barbizon Hotel stationary. Photo by Dashiell King. courtesy of The Georgian Hotel

“From the little girl with a diary who migrated with her single mother as a child to begin a life in a new country, to the woman of many deaths and rebirths whose complexity of life challenged the dominant gender paradigms of our times,” Maciel Antunes said, “I want to remember her as a woman who removed obstacles to create her own freedom and did not wait for it to be given to her.” Nin’s handwritten journals sit nearby in a glass case. Animated by the artworks of our time, you can all but hear her voice floating off the bay, encouraging everyone who passes through “Celebrating a Renegade” to seize their liberty too.

“Celebrating a Renegade” is on view at Gallery 33, 1415 Ocean Ave, Santa Monica, California, through March 22.