Archaeology & History

Ancient Babylonian Tablet May Reveal the Location of Noah’s Ark

The tablet's link to the Biblical vessel was explored in a recent YouTube video by Dr Irving Finkel.

The resting place of Noah’s Ark—a ship said in the Bible to have saved two of every animal during an ancient Great Flood sent by God to flush evil out of the world—may have been located thanks to a 3,000-year-old clay tablet held in the British Museum.

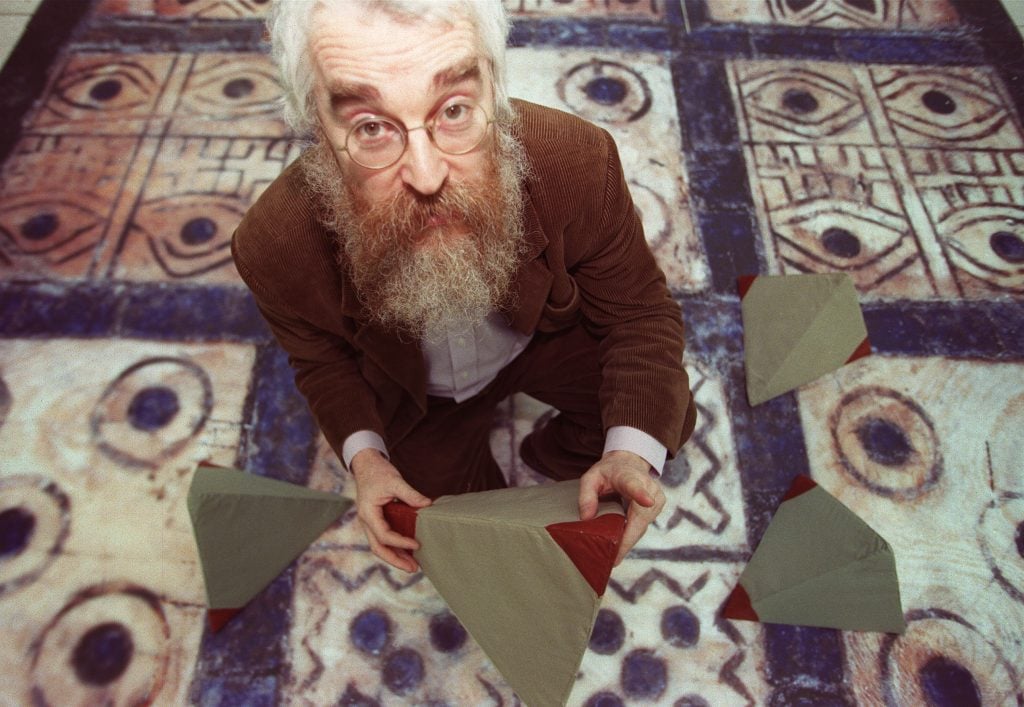

In a video posted in August on the British Museum’s YouTube channel, curator Dr Irving Finkel discussed the tablet—which he called “the oldest map in the world”—as part of his series “Curator’s Corner.” The philologist and assyriologist goes through the marks and inscriptions made on the tablet, which includes a brief description of the creation of the world on its reverse, and explains what it reveals about the story of the Great Flood. Finkel is the author of the 2013 book The Ark Before Noah, which decodes the ancient event believed to have occurred around 5,000 years ago and associated artifacts.

In the Biblical story, Noah is tasked by God to build a large ark and to gather two of every animal onto it to ensure their survival during a 150-day flood sent to cleanse the world of wickedness. In the Babylonian version of this tale, it is a man named Utnapishtim who undertakes this task. Finkel explained that this tablet demonstrated that “the story was the same … that from the Babylonian point of view, this was a matter of fact thing … that if you did go on this journey you would see the remnants of this historic boat”.

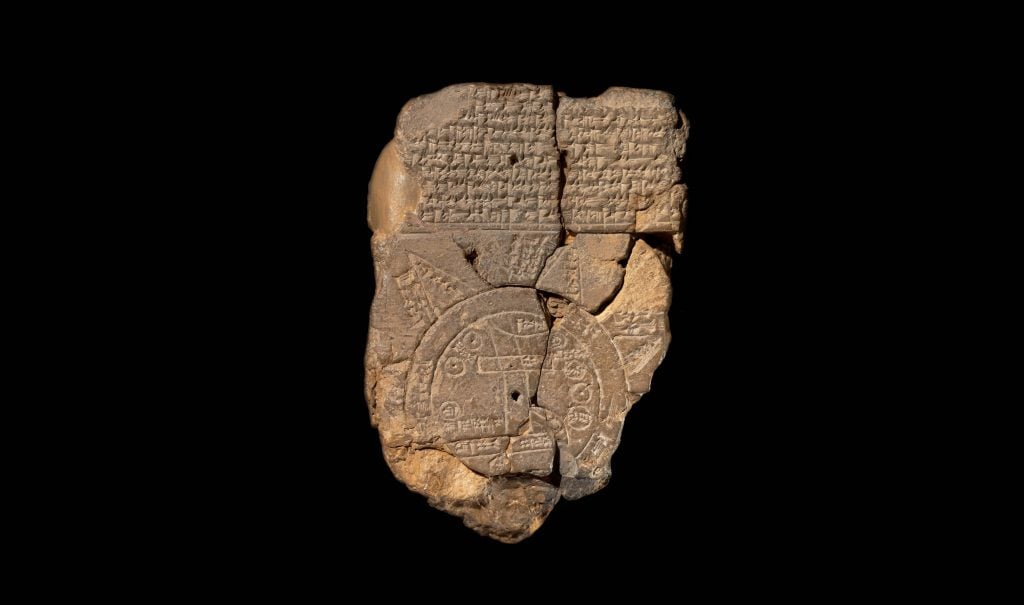

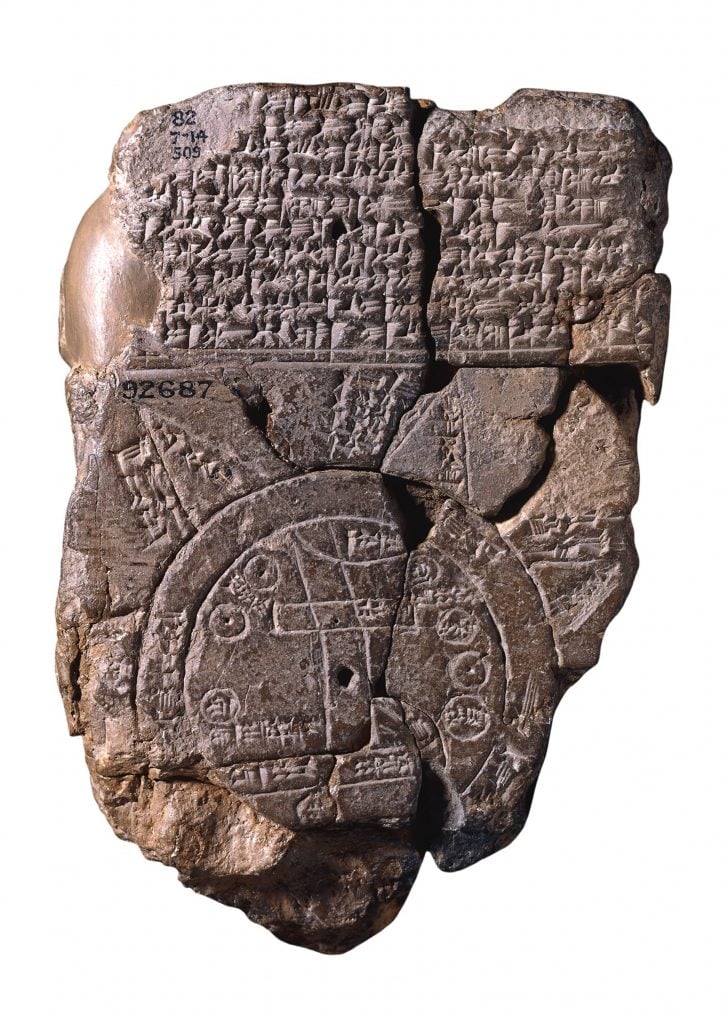

The tablet, called the Imago Mundi, was first unearthed during excavations in Iraq in 1882, and has posed a translation challenge to scientists and linguists for hundreds of years.

The Babylonian Map of the World, c. 510-c. 500 BC. Found in the collection of British Museum. Artist: Assyrian Art. (Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

The tablet shows a circular world map with the ancient city of Babylon represented as a long rectangle. Surrounding the map is a “bitter river,” which ancient Mesopotamians believed to surround the world. It features several paragraphs of cuneiform text—the world’s oldest form of writing, predating ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics—on both sides of the clay. Before damage, the tablet showed eight shapes which researchers have decoded as mountains referenced in the cuneiform.

One key link between the tablet and the legend of the Noah’s Ark was the inclusion of the word “parsiktu.” The term is known to feature on only one other surviving Babylonian tablet, a tablet describing the boat which survived the Great Flood.

The translated text on the reverse of the tablet describes the steps in a traveler’s journey to discover the location of the Ark, describing “seven leagues,” which they must pass through to arrive at the remnants of the ‘parsiktu-vessel’. The map leads to ‘Urartu,’ which was named in an ancient Mesopotamian poem as the Ark’s landing place and is the Assyrian equivalent to “Ararat,”, the mountain location named in the Hebrew Old Testament as the resting place of Noah’s Ark. A location close to Ararat’s summit has long been the speculated location of the Ark’s resting place, as researched by Noah’s Ark Scans. In Finkle’s explanation of the tablet, he explained how ancient travellers taking the path to Urartu may have seen the remains of the mammoth vessel on their journey.

The British Museum’s Irving Finkel. Photo: Johnny Green/PA Images via Getty Images

Biblical measurements given (“300 cubits, 50 cubits, by 30 cubits,” which is equal to around 515 feet long by 86 feet wide and 52 feet high) match up with the measurements of the site in modern-day Turkey, although there is scholarly debate around whether the mountain or Aratat formed after the date of the flood.

In the video, Finkel asks “so what does this actually mean to us?”. He continues to say that “although this is a map which would not encourage you perhaps to moat across Iraq today in a Land Rover, when it comes to operating beyond the limits of the known world into the world of imagination, it’s indispensable. So, for the first time, we can pronounce with authority, that if we were an ancient Babylonian we would know where to go to see the remains of that wonderful boat.”