Art World

Archaeologists Have Discovered the World’s Oldest Illustrated Book in an Ancient Egyptian Burial Site

The writings were intended to aid the deceased through the underworld.

The writings were intended to aid the deceased through the underworld.

Sarah Cascone

Egyptologists have discovered the oldest copy of what is being called the world’s first illustrated book, a 4,000-year-old edition of the “Book of Two Ways,” an ancient Egyptian guide to the afterlife considered to be a forerunner to the “Book of the Dead.” The text predates previously known versions by some 40 years.

The find was first published in the Journal of Egyptian Archaeology in September by Harco Willems, a professor at the University of Leuven in Belgium.

Unlike modern books, these historic writings weren’t inscribed on bound pages, but on the walls of sarcophagi. They were meant to aid the deceased through the perilous journey to the underworld, during which they might be beset by demons or raging fires. If one were to cast the correct spells, he or she might achieve immortality.

Though the plank’s inscriptions reference a governor named Djehutynakht, Willems’s research has revealed that the coffin originally held the remains of a woman named Ankh, referred to throughout the text as “he.” That is in keeping with Egyptian mythology, where rebirth was the purview of male deities, and dead women adopted male pronouns to be more like Osiris, god of death.

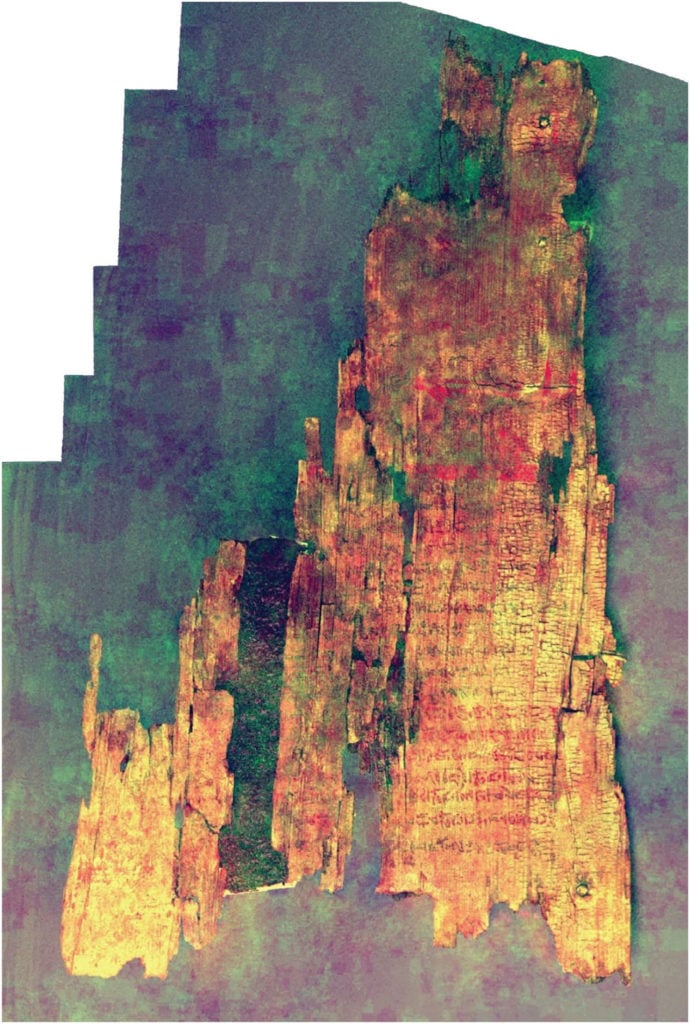

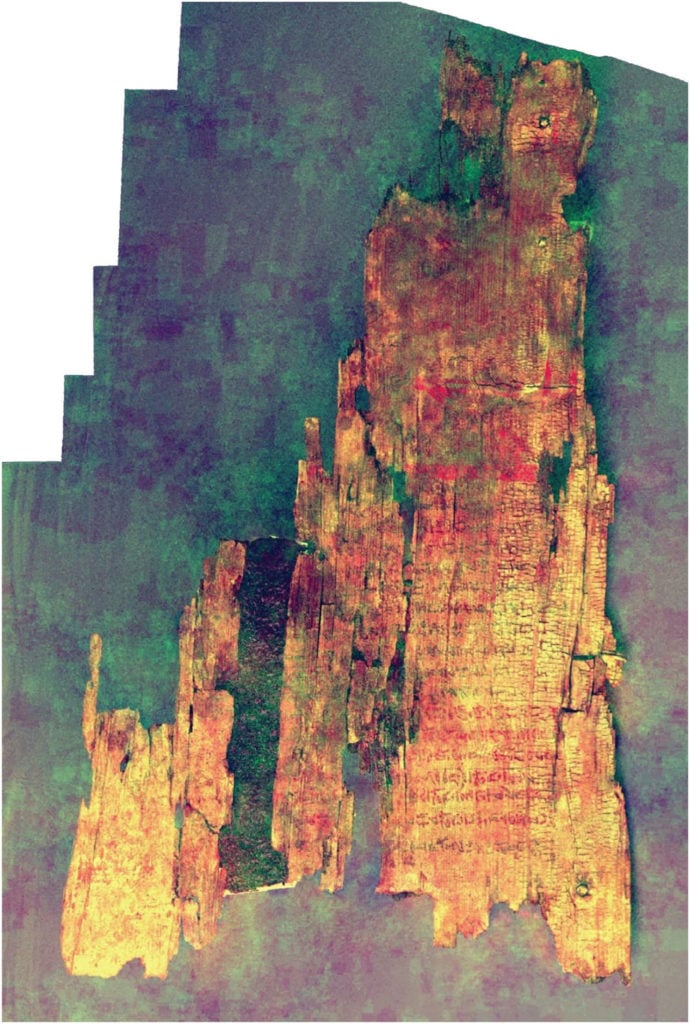

Coffin fragments bearing the earliest known version of the “Book of Two Ways,” an ancient Egyptian text considered the world’s first illustrated book. Photo courtesy of Harco Willems.

“To me, what’s funny is the idea that how you survive in the netherworld is expressed in male terms,” Willems told the New York Times.

The Egyptologist has overseen digs at the Coptic necropolis of Dayr al-Barshā, used as a cemetery during the Middle Kingdom period, from about 2055 to 1650 B.C, since 2001. He excavated the ancient coffin fragments about 20 feet down a burial shaft at the complex of an ancient Egyptian provincial governor, or nomarch, named Ahanakhtin, in 2012.

The fragile state of the artifacts, repeatedly ransacked by looters long ago, prevented them from being studied until now.

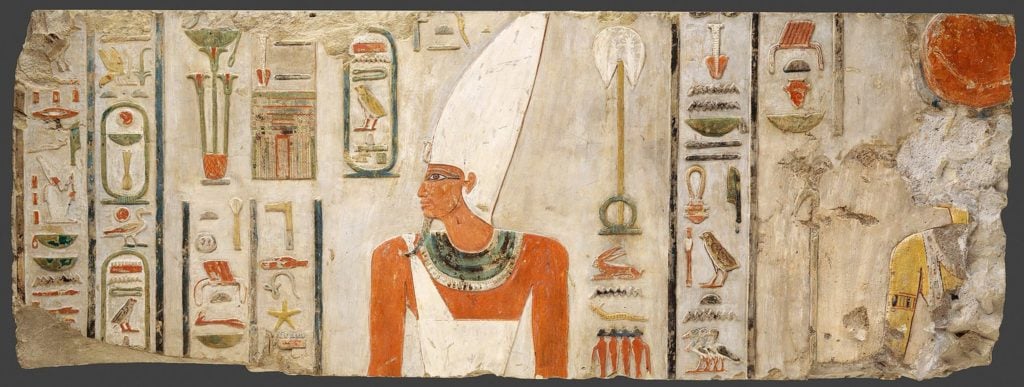

This image of Pharoah Mentuhotep II was found at the site of Deir el-Bahri in Egypt. Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The planks of wood bear carved ink inscriptions and painted illustrations meant to ensure successful passage through the netherworld to Rostau, the realm of Osiris. (The text is called the “Book of Two Ways” because it offers instructions on how to travel either by land or by water.)

The pigments, however, have faded with time, and the faint markings are visible largely thanks to high resolution imagery processed with DStretch software.

Based on inscriptions on other tomb artifacts referencing Pharaoh Mentuhotep II, who reigned until 2010 B.C., Willems believes this newly identified “Book of Two Ways” is at least four decades older than any of the two dozen previously known versions of the text.