In ancient Egyptian mythology, Nut was the sky goddess who protected the earth — personified by her twin and husband, Geb — from the chaos of the great beyond. Each day, she swallowed the sun in the west and gave birth to it in the east.

This Egyptian practice of mythologizing life’s wondrous phenomena belies the astrological rigor with which they interpretted the night sky.

In the third millennium B.C.E., the Egyptians introduced a 365-day calendar and by 1550 B.C.E., they were running on a 24-hour day. Astronomy was crucial for fixing the dates of religious festivals, properly aligning the pyramids, and Egyptian texts record most of the solar system’s planets along with constellations such as Orion and the Plow.

One notable absence, however, is the Milky Way. No name, illustration, or description of the Milky Way has been found in Egyptian texts or visual representations. For the better part of a century, this has baffled Egyptologists. After all, most cultures have a name for the alluring band of iridescence that hangs in the sky.

One theory recently put forward by Or Graur, an astrophysicist at the University of Portsmouth, is that Nut was a celestial manifestation of the Milk Way. The idea was explored in a paper published in Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage that brings together astronomy, Egyptology, and anthropology.

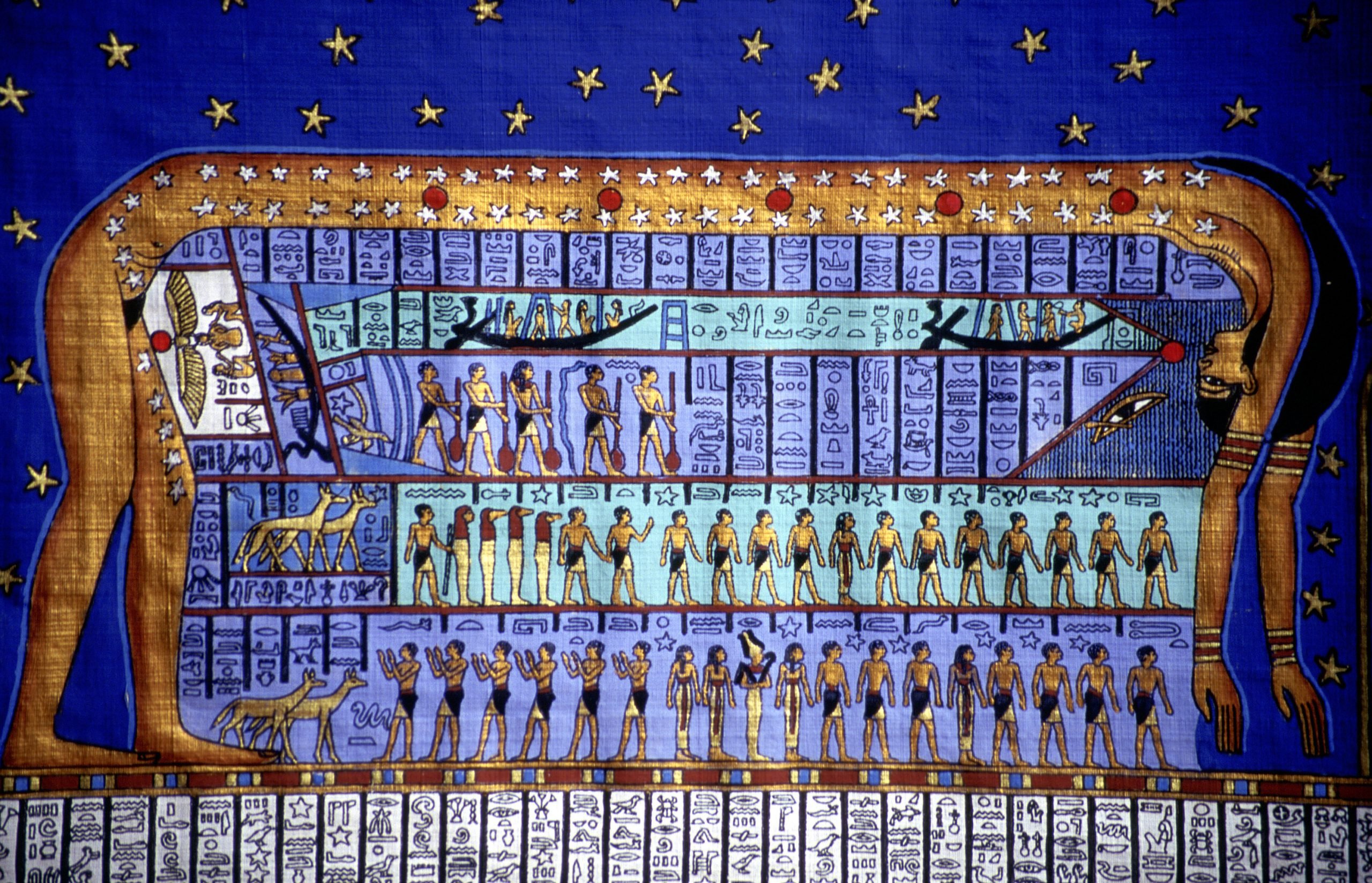

Nut stretches over the Earth, represented by her brother Geb. From the Book of the Dead of the priestess Nesitanebtashru. Photo: Oxford Science Archive/Print Collector/Getty Images.

Most straightforwardly, there’s the manner in which Nut was often depicted on papyri and coffins: as a woman arched over Geb with stars dotted all across her body.

Graur went deeper by using contemporary astronomical software to simulate the appearance of the Milk Way in the ancient Egyptian night sky. He then compared the results with descriptions of Nut in key sources including Pyramid Texts, Coffin Texts, and the Book of Nut.

The most compelling connections came in the Book of Nut. Nut’s head and rear are forever fixed with the west and the east — as necessitated by her role of swallowing and birthing the sun. The descriptions of Nut’s other body parts, however, seem to align with the Milky Way.

“I suggest that the winter orientation of the Milky Way traces Nut’s arms, while the summer orientation outlines either her torso or her backbone,” Graur writes in “The Ancient Egyptian Personification of the Milky Way as the Sky-Goddess Nut”.

For the winter months, her right arm is described as bearing northwest while her left bears southeast. For the summer months, a list of stars is described as tracing her torso. Such an understanding, Graur writes, would place Nut comfortably within multicultural conceptions of the Milky Way.

A further connection arrives through the autumn migration of millions of birds through Egypt, en route to warmer southern climes. Nut is often portrayed sitting in a tree, offering food and drink to the birds. From an Egyptian perspective, the migrating birds seemed to follow the Milky Way — they arrived from the northeast and headed southwest.

This link between the Milky Way and bird migration, Graur writes, is common to several cultures, particularly in Northern Europe. The name given to the Milky Way in Finnish, for example, is linnunrata, bird’s track.

In Egyptian mythology, Nut also played a key role in guiding a deceased king on his journey to the sky to join the stars. Graur furthers the cultural comparison here, citing deities from around the world that have been connected to the afterlife through the Milky Way. This includes Citlalicue from the Tlaxcaltec people of the Puebla-Tlaxcala Valley in Mexico, Hemmawihio from the Cheyenne tradition, and the Celestial River in Chinese mythology, which acts as a conduit for the dead.

As Graur acknowledges, it’s not a wholly conclusive theory. That would require an Egyptian text or painting clearly portraying the Milky Way. Until then, the idea of Nut as an entity that symbolically encompassed the sky, the Milky Way, and much else besides, seems strong.