Art World

Researchers Have Discovered That the Ancient Egyptians Somehow Developed a Complex Yellow Paint Also Used by Vermeer

How artisans in the 5th century BC got their hands on it remains a mystery

How artisans in the 5th century BC got their hands on it remains a mystery

Maxwell Williams

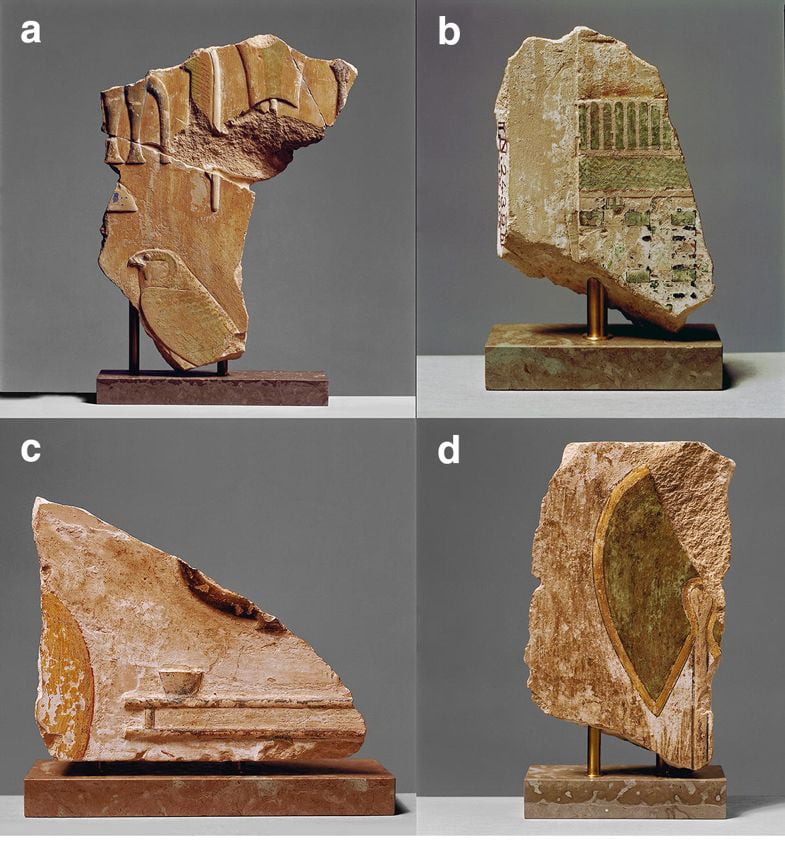

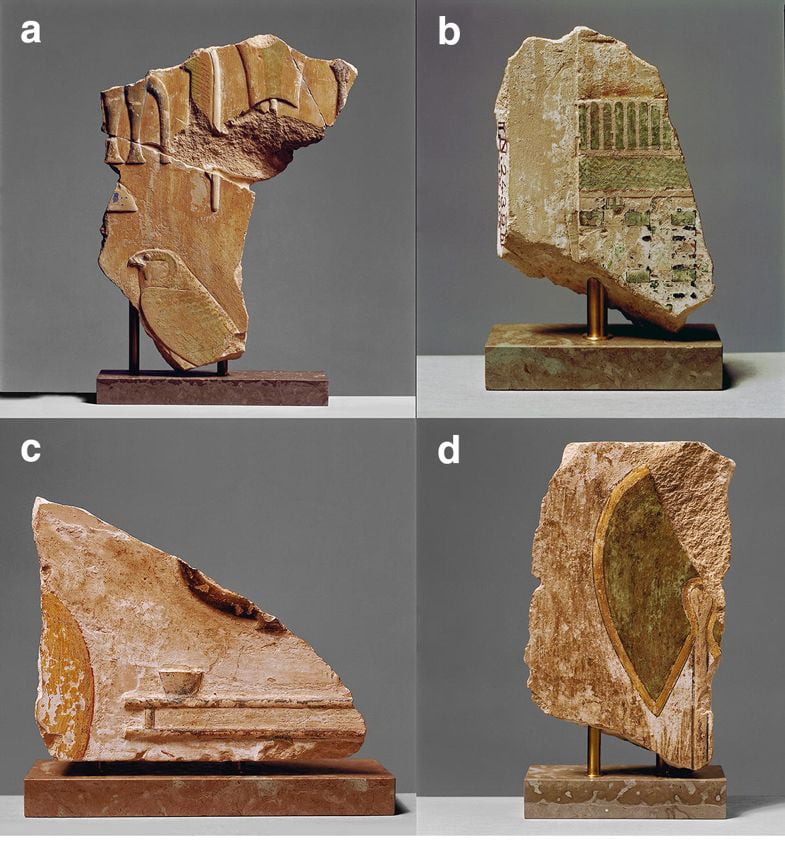

A group of scientists based in Europe have made the discovery that ancient Egyptians used yellow paint that was much more complex than originally thought. Working with limestone reliefs allegedly from the gateway entrance to the palace of Apries—Pharoah of the 26th dynasty of Egypt (589–570 BC)—the archaeologists used molecular identification techniques to study the paint residue on the remarkably preserved surfaces, and found two yellow pigments as-yet-unidentified in Egyptian painting.

Using non-invasive micro-X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy, the scientists found that most of the pigments studied on the reliefs—the reliefs are held in the collection of the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek art museum in Denmark—were expected: previously known compounds of Egyptian blue, Egyptian green, and red ochre were detected. But when it came to the yellow pigments, the scientists decided to dig further and take a sample for use in a technique known as micro-X-ray powder diffraction.

Previously, studies had found that most Egyptian yellow paint was ochre (a mix of clay and iron-rich soil) or arsenic sulfide mineral orpiment. But this time there was an unusual discovery: “It is the first time that lead-antimonate yellow and lead-tin yellow have been identified in ancient Egyptian painting,” the researcher’s paper states.

The study was co-authored by Cecilie Brøns, a researcher at Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek; independent researcher and conservator Signe Buccarella Hedegaard; and Kaare Lund Rasmussen and Thomas Delbey, both chemists at the University of Southern Denmark. It was published this summer in Heritage Science, an open-access journal covering cultural artifacts.

“It was a several-step-process,” Rasmussen tells Artnet News in an email interview about this discovery. He describes putting the X-ray beam of the micro-X-ray fluorescence spectroscope onto the relief and seeing lead, antimony, and tin. At first, Rassmussen thought perhaps the spectroscope was somehow penetrating into the underlying limestone. “But progressive techniques eliminated that possibility,” he explains. “I must say it took many repeated measurements and many discussions about the different techniques before we settled on two unusual and unexpected pigments. Let us say one new pigment was a surprise, but two made us go over our data very carefully. No doubt about it.”

Rasmussen is a chemical analysis expert whose greatest hits include studying the syphilitic bones of medieval Danes, the skeletal remains of Italian monks, the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the facial hair of 17th-century Renaissance astronomer Tycho Brahe (who had a lot of gold in his beard, somehow). In his mind, the discovery of pigments that were used in ancient Egypt, but also show up in 17th-century Baroque painting—Vermeer used the same type of paint—is culturally significant in a few ways, and opens up new questions that will lead to further research down the line.

“There can be several aspects,” Rasmussen says of the findings. One theory is that somehow the formulas for making these yellow pigments was handed down from ancient Egyptians all the way to Dutch Baroque times, which would raise questions about trade routes and the sharing of information. “Another possibility is that the complicated formula is due to a—for us unknown—geological source,” he adds, “which they draw upon in the 5th century BC and also in the 17th century AD.”