Archaeology & History

Ancient Stone Tools Once Thought to be Made by Humans Were Actually Crafted by Monkeys, Say Archaeologists

If monkeys made the tools, it's a major blow to experts seeking to disprove the long-held "Clovis First" theory.

If monkeys made the tools, it's a major blow to experts seeking to disprove the long-held "Clovis First" theory.

Sarah Cascone

Experts are reevaluating prehistoric Pleistocene-era sites in Brazil previously believed to have been home to ancient humans. It turns out, the 50,000-year-old stone tools discovered in excavations are probably the work of capuchin monkeys, not early humans.

“We are confident that the early archeological sites from Brazil may not be human-derived but may belong to capuchin monkeys,” wrote archaeologist Agustín M. Agnolín and paleontologist Federico L. Agnolín in an article published in the new issue of the journal the Holocene.

Excavations at Pedra Furada, a group of 800 archaeological sites in the state of Piauí, Brazil, have turned up stone shards believed to be examples of simple stone tools. Made from quartzite and quartz cobbles, the oldest ones appear to be up to 50,000 years old, which would put them among the earliest evidence of human habitation in the Western Hemisphere.

However, the tools also bear a striking resemblance to the stone tools currently made by the capuchin monkeys at Brazil’s Serra da Capivara National Park.

The monkeys have their own rock quarries, where they select substantially sized rocks to use as hammers to crack nuts against a larger, flattened anvil rock. Rocks also come in handy for eating seeds and fruits—and the monkeys even lick the dust created from driving two rocks together, possibly as a way of adding minerals to their diets.

Stone tools assist capuchins with other tasks as well, such as digging. And the females throw rocks at potential mates as a way of demonstrating sexual interest.

All of these processes can lead to the stones breaking into smaller flaked pieces—which, the new study found, are indistinguishable from some ancient stone tools carved by early humans.

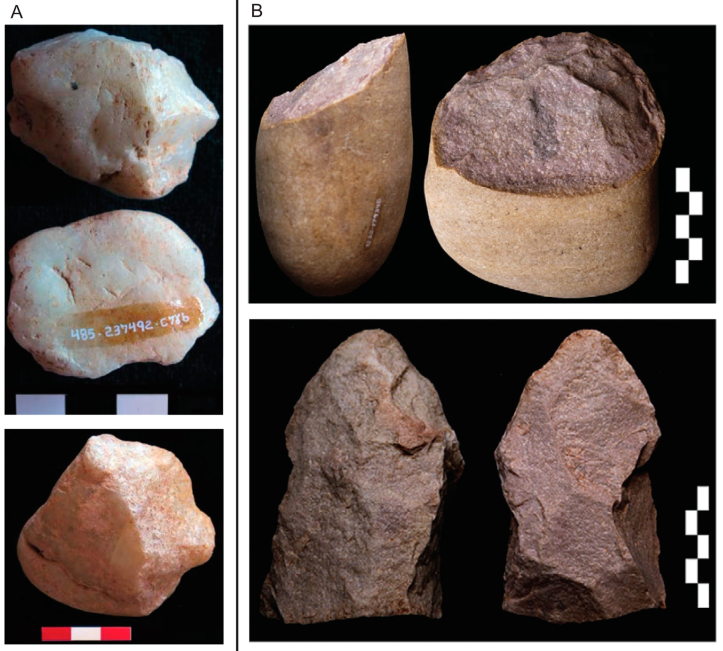

Pebble tools from Pre-Clovis sites in Brazil: A, Vale da Pedra Furada artifacts; B, Toca da Tira Peia artifacts. Photos courtesy of Elsevier.

“Our study shows that the tools from Pedra Furada and other nearby sites in Brazil were nothing more than the product of capuchin monkeys breaking nuts and rocks some 50,000 years before the present,” Federico Agnolín, a researcher at the Argentine Museum of Natural Sciences, told Argentina’s National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET).

The possibility that monkeys were responsible for the human-looking lithic deposits at Pedra Furada was first raised in 2017 by archaeologist Stuart J. Fiedel in the journal PaleoAmerica, noting that capuchins may have been using tools for 100,000 years. Similar concerns were discussed in the journal Quaternaire in 2018.

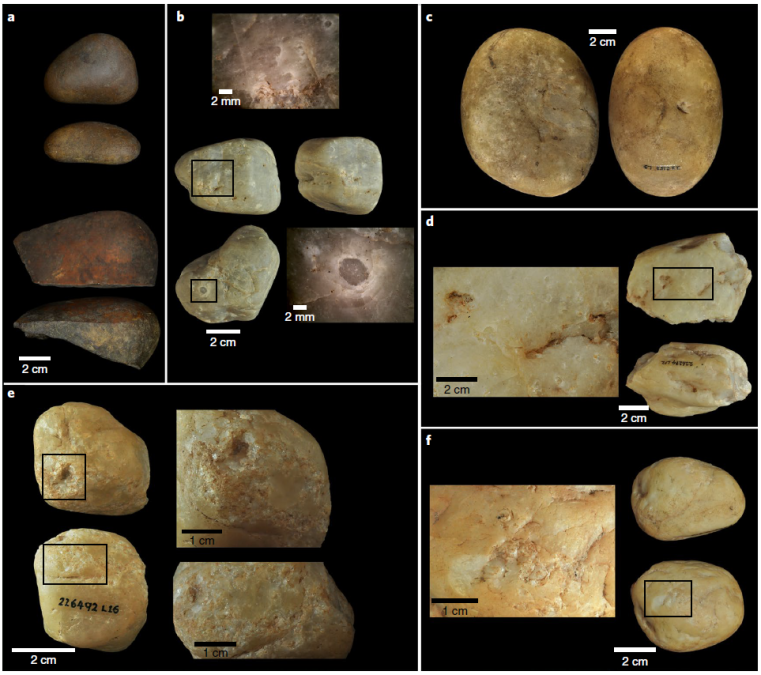

Stone pounding implements used by capuchin monkeys in Brazil. Photo by Tiago Falótico.

A 2019 study published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution was the first to examine stone tool-making practices of the capuchin population at the Serra da Capivara.

Coupled with the lack of other evidence of human habitation from 50,000 years ago, such as concrete traces of dietary remains or hearths—charcoal at the site could have originated from naturally occurring fires—the tools’ resemblance to rock fragments created by monkeys calls into question the likelihood that humans were responsible for their creation.

The new findings could have a major impact on our understanding of when the first humans arrived in the Americas. Pleistocene archeological sites from Brazil are among the most compelling evidence that people lived on the continents prior to the end of the last Ice Age.

Capuchin monkey fracturing nuts using a rock as a hammer and a larger one as an anvil in Northeast Brazil. Photo by Tiago Falótico, courtesy of CONICET.

The once-predominant “Clovis first” theory long held that glaciers prevented significant settling of the Western Hemisphere until around 14,000 years ago. In recent decades, archaeological sites like the Buttermilk Creek complex in Texas, which has evidence of human inhabitants dating back 15,000 years, and Monte Verde in Chile, dated as early as 18,500 years ago, have challenged that hypothesis. There is growing acceptance of the theory that during the Ice Age, people began settling along a coastal entry route.

But support for a Pre-Clovis human presence received a setback last month, when new testing called into question the dating of fossilized footprints at New Mexico’s White Sands National Park to 22,800 to 21,130 years ago—making them the oldest evidence of human occupation of North America. It now appears the seeds used to date the markings may have ingested ancient carbon from the waters of Lake Otero, leading to inaccurate, artificially ancient dating.

Now, Brazil’s capuchin monkeys may have landed another blow against the Pre-Clovis faction.

“Our work reinforces the idea that the human settlement of this part of the American continent is more recent and is in line with the studies that determine its arrival some 13,000 or 14,000 years before the present,” Agustín Agnolín, of Argentina’s National Institute of Anthropology and Latin American Thought, added. “This questions the hypotheses that proposed an excessively old settlement of South America.”