Art & Exhibitions

Andres Serrano Wants New Yorkers To Stop Ignoring the Homeless

His new public art project zooms in on urban nomads.

Copyright of the Artist. Courtesy of More Art.

His new public art project zooms in on urban nomads.

Benjamin Sutton

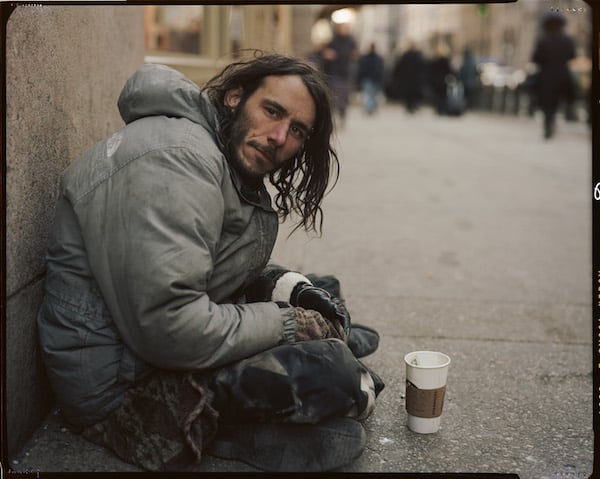

Andres Serrano, Residents of New York (Meow Wolfman) (2014).

Photo: © the artist, courtesy More Art.

Andres Serrano is bringing photos of the homeless to the streets of New York. His latest photo series, “Residents of New York,” consists of large-format portraits of more than 85 men and women who live on the city’s streets. Now 35 photos from the series have been installed outdoors around Washington Square, on phone booths throughout the city, and inside the West 4th Street subway station, among other locales. But the sprawling project, commissioned by nonprofit More Art and on view through June 15, is not Serrano’s first body of work to focus on the city’s homeless.

In 1990 he created a suite of photos called “Nomads,” in which the subjects posed against studio backdrops set up inside subway stations. And then, in 2013, Serrano created the project Signs of the Times, for which he bought some 200 signs that homeless people used to solicit change from passing pedestrians. With this new series on the homeless, his most purely documentary in style, he aims to call attention to a set of New Yorkers who are typically ignored.

New York has a homeless population of at least 60,000—a number that grew by 73 percent during former mayor Michael Bloomberg’s time in office—but many of its citizens are adept at ignoring the city’s less fortunate inhabitants. For Serrano, “Residents of New York” grew very naturally out of his preceding body of work. Much like his portrait series devoted to the Ku Klux Klan or the porn industry, the latest photos confront viewers with the sensitive eyes and empathetic gazes of people whose inner lives we consider all too rarely. Serrano spoke with artnet News about “Residents of New York” and its place within his larger oeuvre.

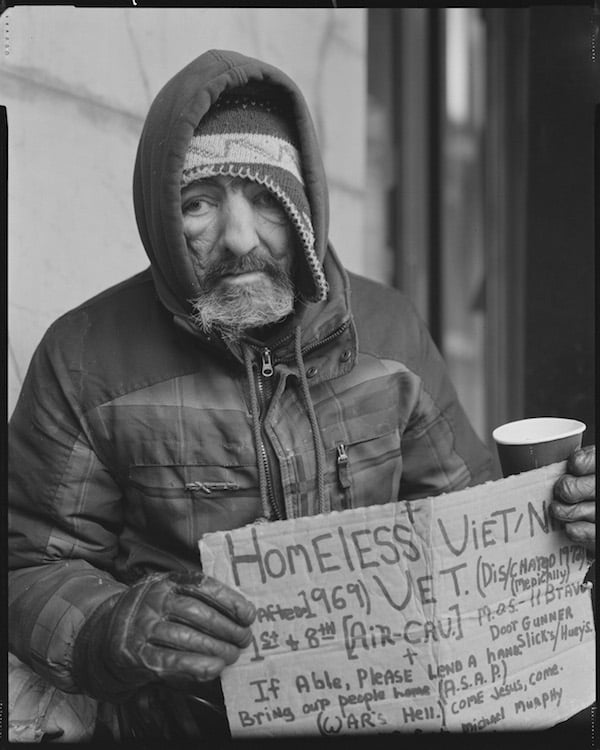

Andres Serrano, Residents of New York (John M. Lavery) (2014).

Photo: © the artist, courtesy More Art.

How did “Residents of New York” come about?

I did portraits of homeless people 25 years ago but at the time I did them in the subways with a backdrop and flash, so they were studio portraits, you couldn’t tell that these people were in the subways. They were studio portraits of homeless people, of the poor. I did another project at the end of last year, I started buying the signs that the homeless use for asking for money, and I made that into a piece called Signs of the Times, a video. I collected 200 signs for that.

That was in late October, and what led me back to the homeless after 25 years was the fact that I noticed more homeless than ever in New York City. I’ve been here all my life, born and raised, but it just occurred to me last year during the month of October how many more homeless people I saw on the streets asking for money. So after I finished the Signs of the Times project I decided in late-December, early-January, to go into the streets and photograph the homeless in four-by-five foot portraits in the streets, meaning don’t put them in an artificial environment, don’t put them in the studio, but treat the street as your studio. So I was there with an assistant, we’d set up a four-by-five camera, and I proceeded to take portraits of homeless people on the streets, and my intent was to capture them the way they are on the street, the way that everyone sees them, although most people don’t see them. Even though they’re there, most people don’t see them.

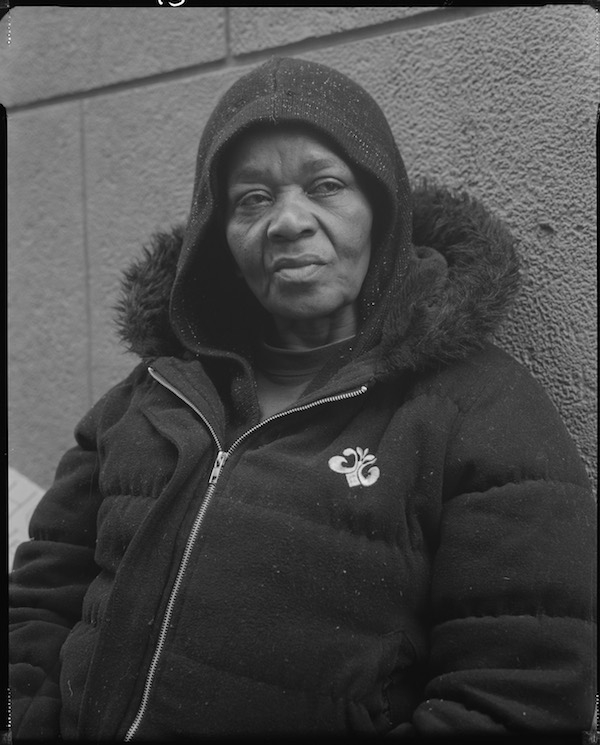

Andres Serrano, Residents of New York (Karen Davies) (2014).

Copyright of the Artist. Courtesy of More Art.

In fact it’s a very curious thing, more than once, as I was photographing someone, the person that I was photographing said to me, “that person always goes by me every day and has never put money in my cup, and because you’re taking my picture now they just put a dollar in there.” And I found that to be true on numerous occasions. And it’s almost like these people are there but you didn’t notice them until you saw me there with an assistant taking a portrait of them, and then you acknowledge them enough to say, okay, I can give you some money.

I called this project “Residents of New York,” avoiding the homeless cliché altogether, and saying these people are residents; they happen to live on the streets, but they’re residents of New York City because they’re living in New York City.

Did you photograph any of the same people for this series as you had bought signs from last year?

A few, not many because by the time I did this project most of those people were gone. There’s a new wave of homeless coming in, but there were some people that I had photographed before.

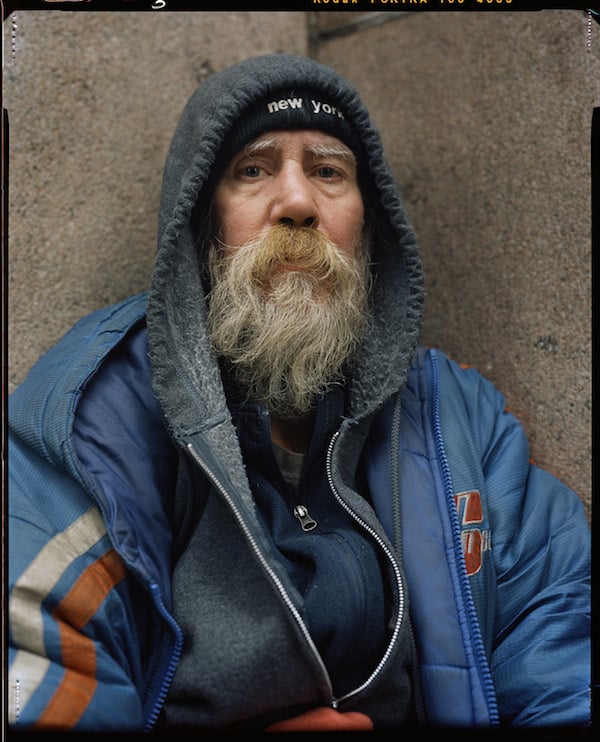

Andres Serrano, Residents of New York (Ryan ‘Red’ and Shelly McMahon) (2014).

Photo: © the artist, courtesy More Art.

There was one young man, I had bought signs from him and his wife before, and when I went up to him this time I said, listen I’m not buying signs anymore I’m taking portraits of people, I’d like to take your portrait, is it okay? He said yeah, sure, fine. And then I looked at him and I looked in his eyes and I said, wow, your eyes are very yellow. And he explained to me that, yes, he’d been sick with jaundice, and he’d been to the hospital and they’d given him medication. So I took his portrait and didn’t think anything of it. And then two weeks later I found out that the boy died. He was probably in his late-20s. Mine is the last portrait of him.

It’s a very odd thing, because someone who I know saw the portrait that I took of that man and she said to me, “I’ve seen that guy on the streets and I never liked him, but now, looking at your portrait, I feel something for him.” And when I told her that he had died two weeks later she felt even more strongly.

So much of your work seems to provoke that kind of reaction, eliciting empathy for subjects you might not expect to feel so strongly.

That word “empathy” is very important because in a way I identify with everyone I photograph. There’s a little bit of me in the people that I choose to photograph, and I certainly try to make them look good, I champion them, I applaud them in some way. I too feel like an outsider, so for me, photographing the Ku Klux Klan, even though I’m not supposed to, it doesn’t feel that strange to me because I’m used to being the stranger, I’m used to being the outsider.

Andres Serrano, Residents of New York (Isaac Nelson) (2014).

Photo: © the artist, courtesy More Art.

You’re best known as a photographer; was it especially challenging to create a kind of social sculpture and video project for Sign of the Times?

It’s more of a conceptual piece. I’ve always said that I’m a conceptual artist. I happen to use a camera, I’ve been called a photographer and I don’t mind being called that, but I see myself as being much more than that. Part of my function in society is to reflect what I see, to be able to capture if not the essence then the spirit of my time. This is certainly in keeping with what I photograph, whether it be the Klan, the poor, sex—it’s in keeping with the temperament of the times.

How did you approach your subjects for this series? How did you decide who you wanted to photograph?

When I was buying signs from the homeless I would approach people in a certain way. Most people who I would approach were always sitting on the sidewalk, and so I would bend down or crouch down, but I wouldn’t sit next to them because I felt that would be too much an invasion of space. I would crouch down and I would say, can I speak to you. And once they invite me to speak to them I would tell them the spiel, meaning: I’m an artist, and artists see things a certain way, and one of the things I see is these homeless signs, and I feel like every sign is a story, so I’d like to buy your story.

When I did the portraits I approached them the same way. Sometimes they knew me, sometimes they had seen me before, sometimes I had even bought a sign from them. But most of them had not met me before. I would say to them: Can I ask you a question? I’m an artist, I’m doing a project photographing homeless people and I can pay you 50 dollars for your time are you interested? And they would say yes and we would set up.

Shooting four-by-five is very different than shooting regular. I’d never shot four-by-five before so I needed an assistant; there’s heavy equipment, there’s a big tripod, so it’s an operation. It takes a few minutes to set it up, and once you do it you only take two, maybe four shots. Rarely did I take more than that. So in a way the model knows that this is special. You’re not going to shoot 1,000 pictures, so they give you their best shot, their best poses right from the beginning. They’re already psyched up for it.

Andres Serrano, Residents of New York (Stephanie Green) (2014).

Photo: © the artist, courtesy More Art.

How did people respond to your spiel?

They all mostly said yes. The only people, one or two, who said no—either to buy the sign or to pose—they’re the kind of people who you normally don’t approach. You see them, they don’t have any signs, they’re not asking for money, they’re just standing around and all they want really is to be ignored and they’re really out there. They don’t need anything from anyone. They’re what I call the walking dead; they’re like zombies. Sometimes they’re filthy, sometimes they’re talking to themselves, and sometimes they have that crazy look in their eyes.

I approached a couple of those characters because I wanted to photograph them, but always at a distance, always respectfully, always saying: Can I speak to you for a moment? And usually they’d say no, or they’d go away, and I’d know, okay, you can’t bother these people, they don’t want to be bothered. Those were the people that would say no. And there were maybe two or three people out of over 100 that I approached like that, but I knew in advance that they would not want to be engaged in any kind of conversation. But everyone else said yes.

How is this series of homeless portraits different from your previous series about homelessness?

It’s different in two ways. Technically it’s different because they’re four-by-five portraits, they’re large format camera portraits. But they’re also a little different in the sense that they incorporate the actual physical landscape around them. Normally I do my work in the studio. Even the “Nomads” series I considered studio work because I had a backdrop to isolate the person from the subway. These are more in situ, they are more location shot.

But when I was out there with the homeless taking these portraits I felt like the street was my studio. In other words, sometimes there were hundreds of people around us, and they’re going right in front of my picture, so I have to wait for a split second for someone to stop before I take my picture. So in a way when you see the portraits you feel like you’re alone with that person even though in reality there were many people around us. So in that sense I felt like I converted the streets into my studio.

Andres Serrano, Residents of New York (Bernice Thomas) (2014).

Photo: © the artist, courtesy More Art.

Did you look to any particular precedents for inspiration when you were preparing this series?

The “Nomads” portraits that I had done in the subway referenced my love of Edward Curtis and his photographs of Native Americans at the turn of the 20th century, where he took the studio to them; he took backdrops with him. But before I started the “Residents” series I started to look at the WPA photographs by Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, all the great photographers who were called in at the moment of the Great Depression and actually recruited by the government to document, record, and monumentalize what was happening in America at that time. In these works I felt like I wanted to reference that work. In fact, some of the portraits I initially did in black-and-white, and except for the date, you wouldn’t be able to tell if these were taken now or 50 years ago. I wanted to evoke that era.

Why did those WPA photographs seem especially relevant now, for this series?

I feel like the homeless are the extreme as far as the ladder of poverty is concerned. There are many who may not be homeless but they’re close to it, they’re at the bottom too, so it’s not only the homeless who are feeling the pinch. Most Americans are feeling it.

Do you worry that people will miss the photographs in the subway since New Yorkers are so used to tuning out anything on a billboard?

I feel like, first of all, they’re—once you walk down those corridors in the subway you can’t escape it. And once you look at one and you realize it’s not an ad and you engage with the person, I think it’s interesting enough if you have the time to be able to say, hey, let’s see what else is down here. Hopefully these photographs are engaging enough that they draw you in.

Andres Serrano, Residents of New York (Chris Cahill) (2014).

Photo: © the artist, courtesy More Art.

What, for you, is the ideal response a viewer can have to this series?

Hopefully next time you see a homeless person you actually see that person and maybe you think, oh yeah, let me give them some money. I’m not a crusader. I have to be honest. It’s not like I’m on a podium here championing the homeless or trying to right an evil. But actually More Art has organized a symposium to be able to engage with the community about the homeless and so they’ll have information about what they’re proposing at the subways. But I feel like it’s enough for me to just bring it to your attention, and then after that it’s up to you to decide what to do with it.

Andres Serrano’s “Residents of New York” continues through June 15.