Law & Politics

The Andy Warhol Foundation Has Won Out Against a Photographer Who Claimed the Pop Artist Pilfered Her Portrait of Prince

Photographer Lynn Goldsmith has vowed to appeal.

Photographer Lynn Goldsmith has vowed to appeal.

Sarah Cascone

Andy Warhol is still making waves, even from the grave. A judge has thrown out a photographer’s lawsuit alleging that the Pop artist unlawfully used her photo of the beloved musician Prince in a series of silkscreen works he began in 1984. The ruling, issued by Judge John G. Koeltl in New York federal court on Monday, brings to an end—at least for now—a contentious legal battle between photographer Lynn Goldsmith and the Andy Warhol Foundation.

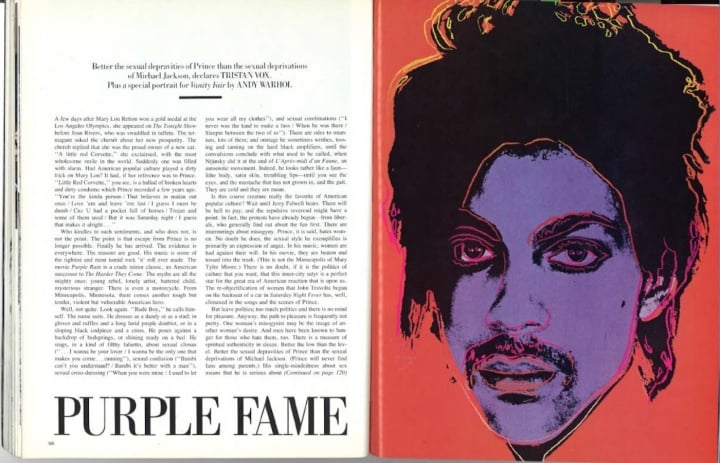

The case has dredged up long-simmering tensions between documentary photographers and fine artists who use their works as source material at a time when some argue the law remains unclear about what qualifies as fair use. According to the judge, this case was a straightforward one: Warhol sufficiently transformed Goldsmith’s photo in his work, fundamentally altering her image of a “vulnerable, uncomfortable person” into “an iconic, larger-than-life figure.”

In his ruling, as reported by the Associated Press, the judge noted that the “humanity Prince embodies in Goldsmith’s photograph is gone.” Furthermore, he wrote, each of Warhol’s Prince works “is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol’ rather than as a photograph of Prince—in the same way that Warhol’s famous representations of Marilyn Monroe and Mao are recognizable as ‘Warhols,’ not as realistic photographs.”

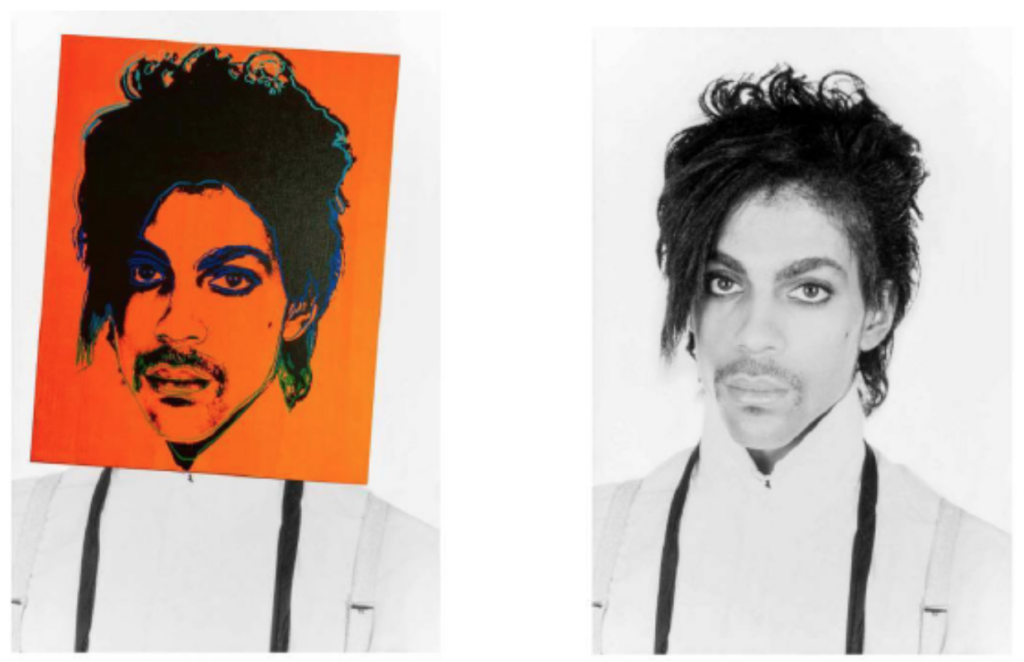

Lynn Goldsmith will continue her legal battle against the Andy Warhol Foundation. Photo courtesy of Lynn Goldsmith.

The legal battle stretches back to April 2017, when the foundation preemptively sued Goldsmith, arguing that Warhol’s use of the photograph was transformative. Goldsmith responded with a countersuit, contending that Warhol’s series infringed on her copyright. Both parties asked the judge to grant summary judgment, which would decide the issue without a trial.

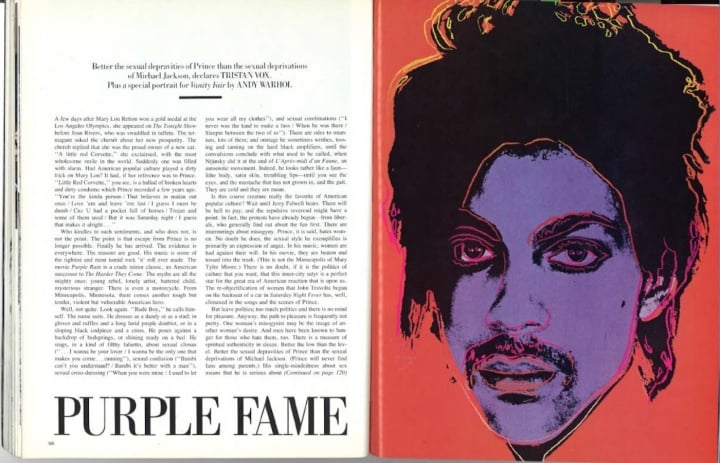

The original image came out of a photo shoot in December 1981 for Newsweek. Goldsmith’s black-and-white photographs were never published, but in 1984, Vanity Fair licensed one of them for $400, and commissioned Warhol to create an illustration for an article about the musician by Leon Wieseltier. The famed Pop artist went on to create 16 works based on the Goldsmith photograph.

“Warhol is one of the most important artists of the 20th century, and we’re pleased that the court recognized his invaluable contribution to the arts and upheld these works,” the foundation’s lawyer, Luke Nikas of Quinn Emanuel, told artnet News. The foundation is also seeking payment, including reimbursement for its legal fees.

Goldsmith, meanwhile, plans to appeal. “I know that some people think that I started this, and I’m trying to make money. That’s ridiculous—the Warhol Foundation sued me first for my own copyrighted photograph,” she told artnet News.

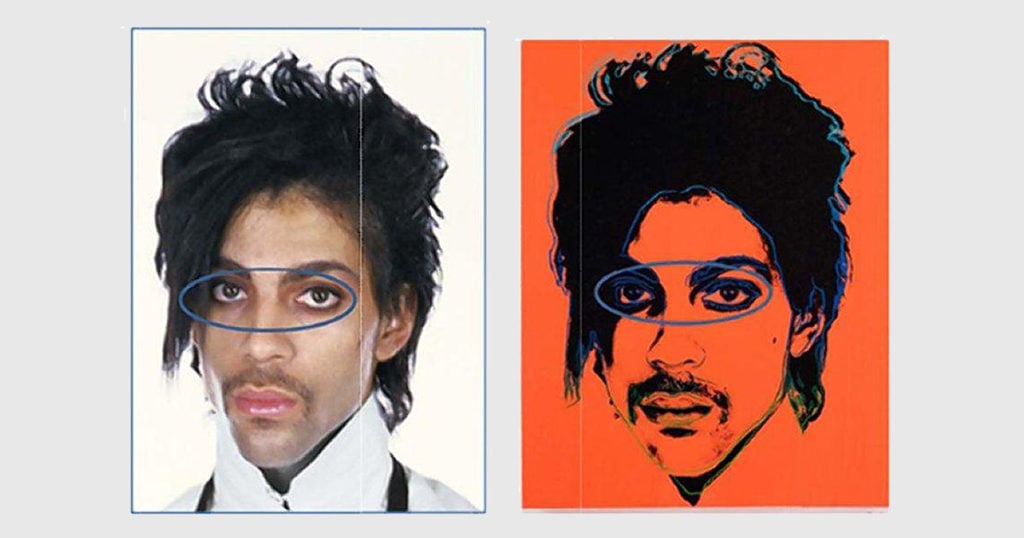

Although the original Warhol work was created in 1984, Goldsmith claims that she only learned of its existence in April 2016, when Condé Nast reproduced one of the silkscreens following Prince’s death. But the judge maintains that while Warhol’s image uses the head and neckline from Goldsmith’s photograph, he “removed nearly all the photograph’s protectible [sic] elements,” altering the color palette and mood of the image.

Andy Warhol’s Prince portrait overlaid on top of the original Lynn Goldsmith photograph of the musician, as reproduced in court documents.

Goldsmith’s lawyer, Barry Werbin of Herrick, Feinstein LLP, disagrees. He claims the decision further hobbles the rights of photographers in “favor of famous artists who affix their names to what would otherwise be a derivative work… and claim fair use by making cosmetic changes.”

The judge’s verdict cited as precedent another high-profile dispute between a fine artist and a photographer: Cariou v. Prince, the 2013 decision that determined Richard Prince’s appropriation art constituted fair use of Patrick Cariou’s photographs. Werbin believes that ruling “stretched ‘transformative’ fair use to new boundaries.”

Lawyer Amelia K. Brankov, who was not involved in the dispute, told artnet News that while this case was fairly cut-and-dry, existing case law still often leaves “artists and photographers with an unclear picture of their respective rights and obligations.”

The original Lynn Goldsmith photograph and Andy Warhol’s Prince portrait of the musician, as reproduced in court documents.

Goldsmith claims to have spent $400,000 in legal bills to date, and expects to accrue costs in excess of $2.5 million. To help offset her legal costs, she’s taken out a loan and launched a GoFundMe campaign that has raised $17,000 to date.

Goldsmith contends her case should matter to any photographer who licenses their work. “My hope is that more of the visual community, particularly photographers, stand up along with me to say that your work cannot just be taken from you without your permission, and to show their support of the importance of what the copyright law can mean not only for me, but for future generations.”

“I’m feeling like David versus Goliath,” Goldsmith admitted. “Do you think I want this battle? But if I don’t do it, what happens to all artists in the future?”