On View

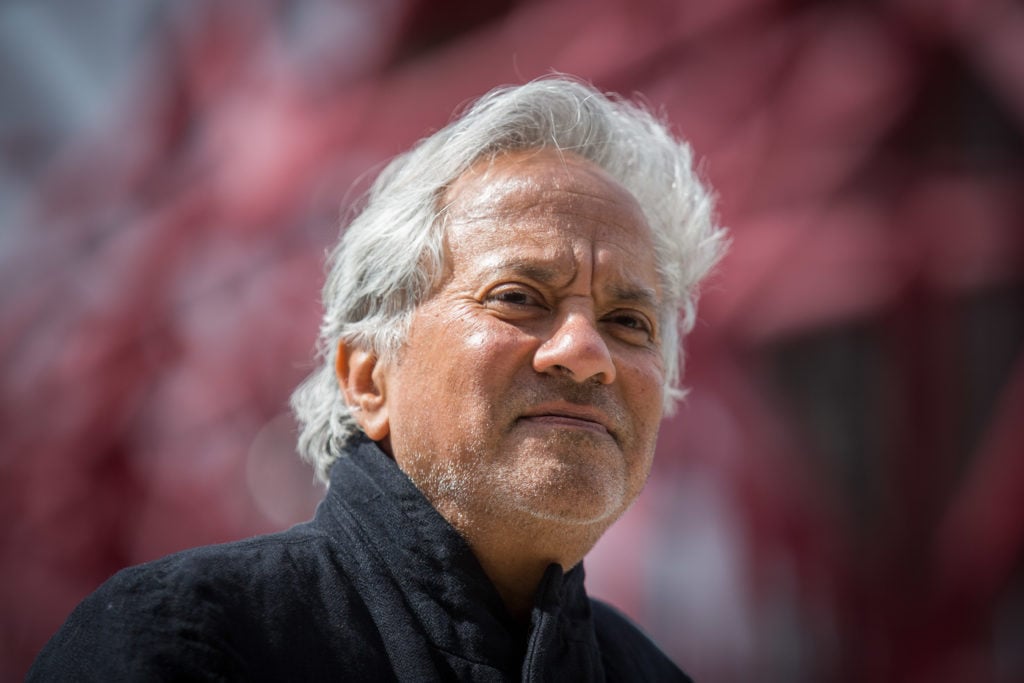

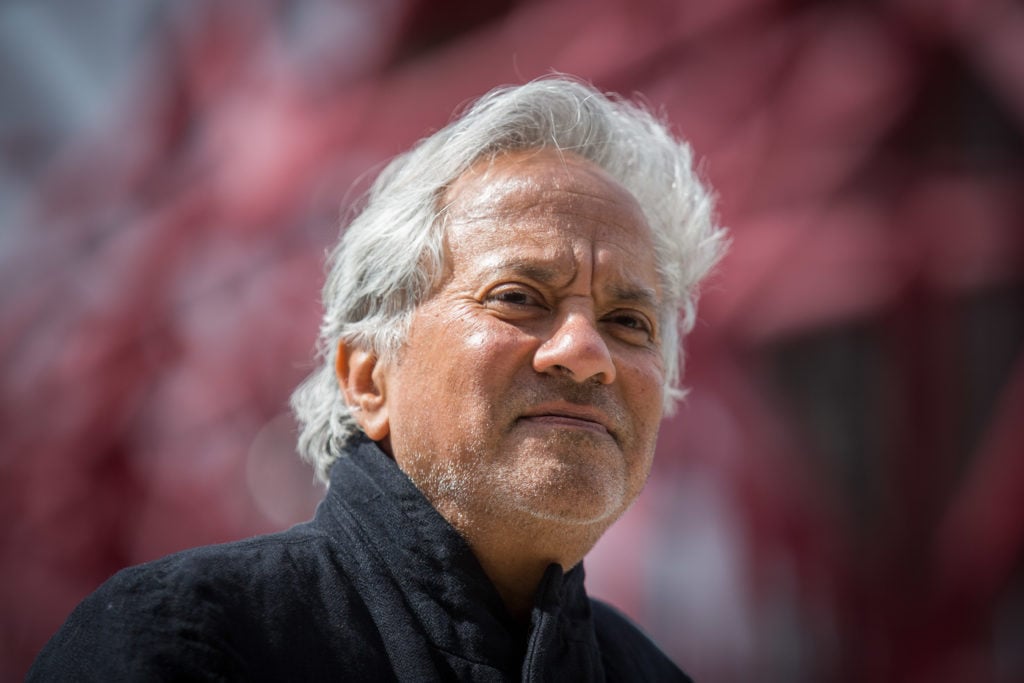

‘I’m Obviously in Pursuit of My Feminine Self’: Artist Anish Kapoor Explains His New Paintings

The artist's latest works are on view at Lisson Gallery in London.

The artist's latest works are on view at Lisson Gallery in London.

Louisa Elderton

Everyone has blood coursing through his or her veins; everyone bleeds. But only women menstruate, and only women know how it feels. So “is a man allowed to deal with women’s questions?” That’s what Anish Kapoor asked artnet News on the occassion of his new exhibition at Lisson Gallery in London, which includes large-scale, untitled paintings of red, pink, and black pigments gushing from curved vulva-like orifices.

Initially, the paintings seem violent, and the artist said they conjure up thoughts of “death, decay,” and are “associated with the abject and impure.” The paintings are indeed messy—dirty, even—with congealed matter flowing from fleshy forms. Pain and sacrifice are channeled with a nod to ritual. Yet conversely, the works also have life force; swift, gestural brushstrokes stir with movement and energy. They pulse with vitality.

“I’ve made so-called bleeding paintings [since] the early 1980s, and I’ve gone back to it again and again, often not with oil paint,” said Kapoor, who is still known best as a sculptor. “Twenty years ago I made a work that was a hole in the wall with red liquid flowing out into a tank. I’ve wanted to do this forever.”

Such older abstract works clearly suggest similar matter, not least Shooting into the Corner (2008–09), where a pneumatic compressor fired 11-kilogram balls of shiny red wax into the corner of a room. Similarly, in Svayambh (2008–09), Kapoor slowly passed a huge wax mass through the vast arched doorways of the Royal Academy in London, sculpting the work according to the space and leaving behind sticky, crusting deposits of dark matter on the walls.

Kapoor’s new canvases deal with the same themes of entropy. “Don’t think, just do,” the artist said to explain how he makes paintings, and these were made swiftly, in just two or three hours. Comparing them to the sculptures in the exhibition, which took months to carve—including one work made from a huge cuboid of pink onyx, within which two labia-shaped forms are nestled—he cited Michelangelo’s belief in an inherent form being slowly revealed. Ultimately, for Kapoor, it’s about “whether the gesture is believable.”

Anish Kapoor, Brink (2019). © Anish Kapoor, courtesy of Lisson Gallery, London, NY, Shanghai.

So are his gestures believable? While Kapoor’s association of menstruation with abjectness speaks to a rather misanthropic gaze, what the paintings also do is suggest a stirring power. Take, for example, two untitled works, both from 2019, where deep red, crescent shapes emerge from fiery swirls of orange, red, and yellow, a shape suggesting the meeting between the moon and Taurus. “I’m goddess obsessed,” the artist said. “That’s what she is: Luna. She’s powerful, she’s not passive. Her interior is dangerous.”

Kapoor’s phrasing was especially significant given the vote by Alabama lawmakers on Tuesday night to ban abortion in practically all cases across the state. But a day before the vote, Kapoor spoke only generally about politics. “I’m a great believer in political correctness,” he said. “The horrible right have trampled on political correctness in the most revolting way. The whole point of artistic endeavor is that it’s fiction.” Meaning? “I imagine what it’s like to be you, and you imagine what it’s like to be me,” he said, adding that he was “obviously in pursuit of my feminine self.”

Anish Kapoor, “Dirty Corner” at Versailles. Photo: JARRYTRIPELON/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images.

But when politicians are controlling women’s bodies, bodies are political. And while art may imagine a fiction, it also points to tangible realities. “My political reflection is not what the work’s about,” Kapoor says, emphasizing that “they are partial forms with voids pouring out.” However, it’s hard as a viewer not to draw further associations, especially as women’s bodied are becoming subject to draconian laws.

The strength of Kapoor’s paintings and the way he thinks about his art is his capacity for empathy. “I can only talk about me or my body as implicated,” he says. “My body is your body, your body is my body. We cross-reference.” And though Kapoor knows that painting is not the same as politics, it’s impossible to the avoid the implications of his latest work. Empathy is about cross-referencing. Violence is about power and control. And Kapoor knows the difference.