Up Next

Anna Uddenberg’s Body-Twisting Sculptures Probe—and Breach—the Limits of Femininity and Reality

Uddenberg's creations skewer our smart-phone-obsessed lives, while capturing elements of their fascination.

Uddenberg's creations skewer our smart-phone-obsessed lives, while capturing elements of their fascination.

Devorah Lauter

Around 2009, while Anna Uddenberg was commuting to Frankfurt’s prestigious Städelschule from her hometown in Stockholm, she opened an inflight pamphlet. Inside was an ad selling alternate identity “experiences”: become a rockstar for a day with a cheering audience, or a supermodel and spend an afternoon at the studio, it beckoned.

“I was fascinated by the question of why one would like to buy something that’s so obviously fake,” said Uddenberg.

The incident helped ignite a new direction in Uddenberg’s practice. The Berlin and Stockholm-based artist has garnered a devoted international following for her piercing interpretation of our TikTok-accelerated tendency to imitate socially constructed behavior and language, possibly to the point of losing our grip on reality and ourselves. Assuming we’d ever grasped it in the first place.

“I’m curious how people are using social media platforms, and how we’re influenced, or even conditioned, by algorithms today. How is this shaping our sense of selves, and how, ultimately, are we willfully turning into products?” she asked over Zoom. “The notion of what’s ‘natural’ or ‘authentic’ has been copied so many times, it’s completely detached from any reference that could be thought of as an original. Maybe we’re all just wild mutants at this point.”

Uddenberg’s earlier, well-known sculptures of contorted, anime/Kardashian-esque female figures—their faces hidden, and bodies bound with futuristic, faux synthetic, luxurious elements—do have a mutant, sexualized nihilism to them. They manage to both skewer our consumer and smart-phone-obsessed lives, including their binding demands on women’s bodies, while also, uncomfortably showing elements of their attraction. The results are jolting.

Installation view of “HOME WRECKERS” at The Perimeter, London. Courtesy the artist and Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin. Photo: Stephen James.

Anna Uddenberg, Journey of Self Discovery (2016). Courtesy the artist and Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin

When Uddenberg showed her sculpture of a scantily clad woman in athleisure and Crocs taking a selfie of her anus at the 2016 Berlin Biennale, some were aghast. “From the Pergamon to this in 2,000 years,” commented Jason Farago for the Guardian. But her layered practice does more than deliver any singular shock or message, and the Berlin exhibition, including her series, “Transit Mode – Abenteurer” (2014–16), also drew critical acclaim, becoming a turning point in Uddenberg’s wider recognition. Her work has been exhibited in Taipei Fine Arts Museum, Centre Pompidou Metz, Athens Biennale (2018), the Moderna Museet, Stockholm, and the Marciano Art Foundation, Los Angeles, among others, and she created pieces for Balenciaga’s 2021 Crocs campaign.

At the time we spoke, Uddenberg impressively had three institutional shows on view at once: “Home Wreckers” at London’s The Perimeter; “Premium Economy” at Kunsthalle Mannheim (though April 21), celebrating her recent Hector Prize; and the Overbeck Prize exhibition at the Overbeck Gesellschaft Kunstverein Lübeck (though January 28), showing her “Big Baby” (2021) series.

Uddenberg also debuted her first film, Useless Sacrifice, on December 14 via Black Cube Nomadic Art Museum’s YouTube Channel, an early version of which appeared at The Perimeter. The film features performers interacting with Uddenberg’s latest “sculptural scripts” in three recent exhibitions, a term she attributes to the pieces because their form guides the viewers and actors.

Installation view of “Continental Breakfast” at Meredith Rosen Gallery, New York, 2023. Performers: Sally Von Rosen and Madalina Stanescu. Photos: Dario Lasagni. Courtesy the artist, Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin and Meredith Rosen Gallery, New York.

One of the exhibitions in the film, titled “Continental Breakfast” at Meredith Rosen Gallery in New York, went viral last spring, attracting millions of viewers, with many bewildered by the artist’s contraptions. They were cordoned off with crowd-controlling straps, and mounted in BDSM-suggestive positions by expressionless women dressed in tailored skirt suits, black heels, and slicked buns. The sculptures were expanded upon in the current “Premium Economy” show at Kunsthalle Mannheim, and fuse associations ranging from gynecological examination chairs and ergonomic workout machines, to alien spaceship travel. Their aesthetic design and airline-style seatbelts are familiar, but any attempt to decode their use is repeatedly foiled. They have none.

“On the surface, it looks legit, and then you look closer, and you wonder, ‘what is this’?” said Uddenberg. “Functional objects tend to tell us they are there for a reason, though their tasks can be questionable. Are tools serving us or the other way around? I’m curious about this quasi-functionality, and my work exists very much in that sphere of confusion.”

Anna Uddenberg, “Premium Economy” at Kunsthalle Mannheim, 2023, Photo: Jens Gerber © Kunsthalle Mannheim / Jens Gerber. Courtesy the artist, Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin and Meredith Rosen Gallery, New York.

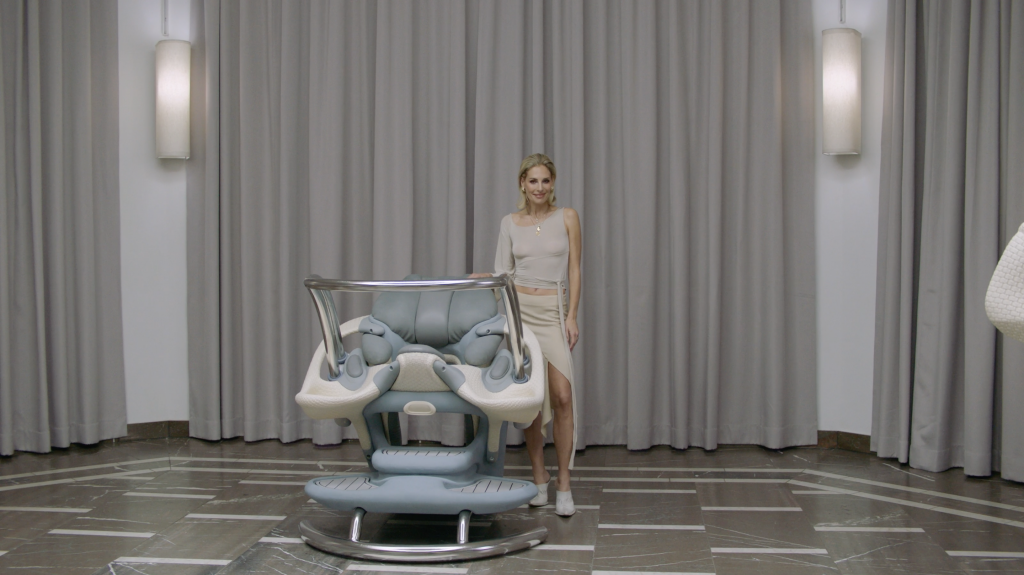

The film begins in the exhibition “Fake Estate” at the Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin, featuring large, pale blue and egg cream-colored, faux-rattan wicker, and metal objects, at times evoking devices for rocking babies, or strange beauty-related procedures. A slim, blond woman presents them to viewers in a sterile showroom setting, posing with an unwavering, softly fixed smile, while blank-faced, young men wearing adult diapers wait to climb into the pieces.

To create these sculptures, the artist said she combines layers of prefabricated and “aspirational,” or luxurious-seeming materials and forms, which she calls “triggers,” for their recognizability. They coalesce into a language that “simulates our reality,” and “contains elements that want to perform or look functional,” she said.

In that sense, Uddenberg’s sculptures share much with their human counterparts, and vice versa. Both “want” to appear a certain way. Both perform or mimic behavior. Indeed, the disturbingly believable aesthetic of the artist’s absurdist sculptures cut close to home, reflecting a warped mirror of our lived reality that is both intriguing and terrifying.

Anna Uddenberg, “FAKE ESTATE,” 2022, Schinkel Pavillon, Still by Thiago Sainte. Courtesy the artist, Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin and Meredith Rosen Gallery, New York Sainte.

“I’m interested in what ‘performativity’ actually means,” particularly concerning gender, and how algorithms “amplify” aspects of it, said the artist, who studied Judith Butler’s writings on the topic, and examines perceptions of “normal” and “authentic” behavior.

For an early performance work on what it means to be a so-called “It Girl,” she learned the 1920s Hollywood-coined term was rooted in “being effortlessly cool and sexy,” a concept Uddenberg said was key. “If you’re doing something effortless, it comes off as authentic, or ‘real,’ but the moment this effort starts to show a little, that’s when people say the person is fake or ‘trying too hard.’” This, she says, is the moment “you can see the glitch in the matrix.”

Anna Uddenberg, Useless Sacrifice (film still), 2023. Courtesy of the artist and Black Cube Nomadic Art Museum.

Uddenberg, born in 1982, said she struggled to understand codes for behavioral norms while growing up. “All of these gender-conformative rules that we’re supposed to know—I had no idea what any of that was, and it got me in trouble many times,” she said. “I had a hard time navigating what is normal for girls to do, and was being slut-shamed a lot for the way I was dressing and acting.”

Uddenberg grew up in a lower-income suburb of Stockholm, which has become more affluent. She said her mother was Sweden’s first certified female boatbuilder and a beautiful woman who often had a fuzz of sawdust about her. She was less interested in “coded femininity,” however, so Uddenberg gleaned what she could from pop culture, which fascinated her. “I loved pink and was obsessed with feminine stuff,” Uddenberg remembered. But she went overboard.

“I was always stepping over some invisible line, where it was either too much, or too little, and that’s where you can start navigating and defining what it is that’s considered normal—‘normal’ itself is actually pretty weird,” she said.

Learning about feminism became her “survivor’s handbook,” but Uddenberg’s work doesn’t clearly advocate for female empowerment or even a blanket criticism of our digital age. On that last topic, she said, “there’s, of course, a lot to be critical towards, but my approach as an artist is to try to engage while also recording my own experiences in this engagement, whether that’s something pleasant or not.”

As for depictions of women, the performers in “Continental Breakfast,” and “Premium Economy” strap themselves into positions associated with submission and degradation, yet they appear to maintain a certain authority, despite physical strain.

Uddenberg did not want to over-explain her approach to this question, but she is curious about “different power dynamics,” she said.

“For some, there’s joy or even a sense of agency in adopting a so-called ‘degrading’ position.’ What’s considered ‘empowering’ doesn’t look the same for everyone,” she added. “I’m interested in the ambivalence of the experience of power. Subverting or breaking with fixed ideas of power is one way to dismantle these stereotypes.”

Useless Sacrifice was co-commissioned by Black Cube Nomadic Art Museum, The Perimeter (London), and Kraupa-Truskany Zeidler (Berlin). The film marks the culmination of Anna Uddenberg’s Black Cube Artist Fellowship.