Museums & Institutions

Apex, the $44 Million Stegosaurus Skeleton, Enters a New York Museum

Ken Griffin, who purchased the fossil, has loaned the specimen to the American Museum of Natural History.

On Thursday, the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York dropped a massive beige curtain and revealed that Apex, the most complete stegosaurus skeleton ever discovered, will be on view starting Sunday for the next four years.

Hedge fund billionaire and renowned museum patron Ken Griffin bought this 150-million-year-old specimen for $44.6 million at Sotheby’s this summer, making it the most expensive fossilized skeleton ever sold—unseating Stan the T. Rex, sold by Christie’s. Poised at 11.5 feet tall and 27 feet long in a classic, defensive posture, Apex has 80 percent of its 320 original bones, and ranks as the most mature stegosaurus of the few complete examples scientists have unearthed since 1874. These specs, paired with Apex’s pristine provenance, paved the way for its record-breaking auction results.

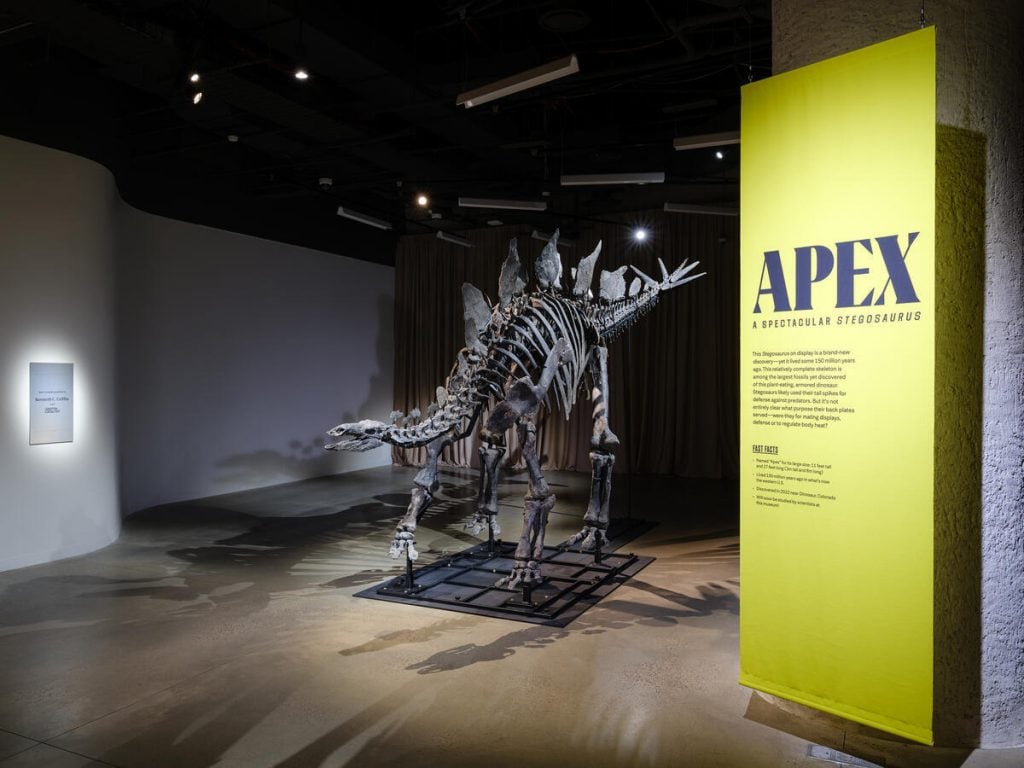

Apex on view in the American Museum of Natural History’s Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation. Photo: Alvaro Keding & Daniel Kim/© AMNH.

“Apex was fresh out of the ground, offered with full rights,” Sotheby’s head of Science and Pop Culture Cassandra Hatton, who worked with Apex’s discoverer from excavation to assembly, has said. “And buyers were coming to me asking for transparency in the market.”

Soon after acquiring Apex, Griffin declared his desire to loan the specimen out for the public good. AMNH contacted Griffin to pitch itself. “We made a case that the work we could do here was something that was really going to advance the broader scientific understanding,” the museum’s President Sean M. Decatur recalled.

The Apex Stegosaurus on view in the American Museum of Natural History’s Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation. Photo: Alvaro Keding & Daniel Kim/© AMNH.

Griffin, who has donated to the museum once before, but never worked with its paleontology department, clearly accepted. “The joy and awe every child feels coloring a Stegosaurus with their crayons will now be brought to life for the millions of people who have the opportunity to see this epic dinosaur in person,” Griffin remarked in press materials.

AMNH probably didn’t bid in last summer’s auction. Over email, a representative told me the museum predominantly grows its dinosaur holdings by sending museum scientists out into reptile-rich areas like Scotland, South Africa, and Wyoming. But while he didn’t happen to outbid this particular institution, Griffin’s acquisition and loan still marks the latest installment in ongoing debates regarding whether such relics should belong by default to the scientific community.

As such, Griffin is also funding a new three-year postdoctoral paleontology fellowship centered on studying Apex. Roger Benson, AMNH’s Curator of Paleontology, will oversee the program, which will predominantly use Apex’s remains to research stegosaurus biology and growth patterns.

Assembly of the Apex Stegosaurus at the American Museum of Natural History. Photo: AMNH.

Scientists typically resist studying privately owned fossils, since there’s no guarantee they’ll be accessible in perpetuity. According to AMNH, Griffin has stated his commitment to continually make Apex available for researchers. A piece of the dino’s thigh will be removed for analysis—and permanently retained in AMNH’s scientific archives. The museums will also make a 3D scan of the skeleton for expert use. The institution hopes these measures set a precedent for how the public and private sectors can collaborate on archaeology.

Apex will first go on view in AMNH just inside the Gilder Center, then move to the entrance of the museum’s fossil hall next Fall. A cast will replace Apex’s actual skeleton after its tenure ends.