Archaeologists in Jordan and Saudi Arabia have found what they believe to be by far the world’s oldest to-scale architectural renditions. The stone engravings, which were made between 7,000 and 9,000 years ago, represent “desert kites,” landscape-scale traps built by early humans to hunt herd animals.

The engravings show the Neolithic structures, which the authors say were probably crucially important to the societies that built them, with the kind of precision that would normally only be possible from the air. Both objects were found in 2015 and a study of them was published this month in the journal PLoS ONE. No other artifacts from this time period show such mental mastery of spacial perception, the authors say.

“It’s mind-blowing to know and to show that they were able to have this mental conceptualization of very large spaces and to put that on a smaller surface,” Rémy Crassard, an archaeologist at the French National Center for Scientific Research and the paper’s lead author, tells the New York Times.

An engraved stone discovered in Jibal al-Khashabiyeh, Jordan. Courtesy PLoS ONE.

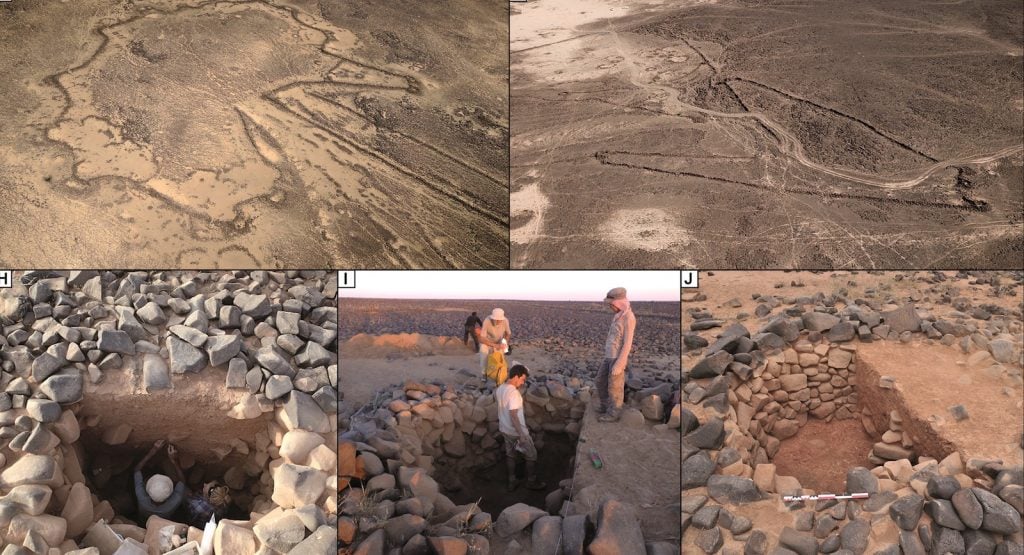

More than 6,200 of these “desert kite” structures have been found, from the Middle East to Central Asia. The were likely used as enclosures in which hunters could more easily contain and kill animals like gazelles, with pits as deep as 13 feet surrounding the edges for any creatures that tried to escape. They are most common in southern Syria, eastern Jordan, and northern Saudi Arabia, according to research by Crassard and his colleagues, done as part of the project Globalkites.

Only a few plans or maps of such large human-made structures survive from before the ancient civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt, the authors say. And while other engravings showing kites had been discovered, they could not be related to specific structures.

The two new scale engravings were found in the Jibal al-Khashabiyeh area, east of the Al-Jafr Basin in Jordan, and the Jebel az-Zilliyat plateau of the Nefud Desert in Saudi Arabia, separated by some 166 miles.

At Jibal al-Khashabiyeh, the engraving, in low relief, was found on a 200-pound, 31-inch block of limestone. It was discovered during a pedestrian survey of a drainage feature of the plateau. The “driving lines,” along which animals were likely herded, stretch over about 16 inches, and lead to a star-shaped enclosure of nearly a foot, with the pit-traps as much as two inches wide. A mysterious graphic pattern nearby, the authors say, may represent a part of the trap not preserved, such as a net.

The Jebel az-Zilliyat engraving was found on a 12.5-foot-long boulder, and has nearly three-foot-long driving lines, leading to a star-shaped enclosure about two feet wide.

While not ruling it out, the authors hypothesize that the engravings were less likely used to plan the structures, since major topographic elements aren’t depicted. More likely, they write, the engraving was used to help organize the collective hunt, determining, for example, how many hunters would be involved and where they would be stationed, and to coordinate their actions.