Archaeology & History

Findings from Pompeii Reveal More About Ancient Inhabitants

They may have shut themselves in to avoid pumice that was raining down on the city, but those very stones may have trapped them inside.

They may have shut themselves in to avoid pumice that was raining down on the city, but those very stones may have trapped them inside.

Vittoria Benzine

Archaeologists in Pompeii have unearthed two more victims of the estimated 16,000 total who perished during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in the year 79 C.E. Skeletons of a middle-aged woman and a young man both emerged immortalized in the positions of their deaths, surrounded by their personal effects. The Archaeological Park of Pompeii announced the find on Monday, outlining all the relics recovered, as well as the ways in which they help humanize this famed tragedy.

The findings came to light in Room 33 of Pompeii’s Region IX, Insula 10, which researchers have been investigating since 2023 “as part of a larger project to secure the edge of the site,” according to this week’s release. Room 33 was a small service area being used as a temporary bedroom during renovations on the site’s larger villa just before the eruption.

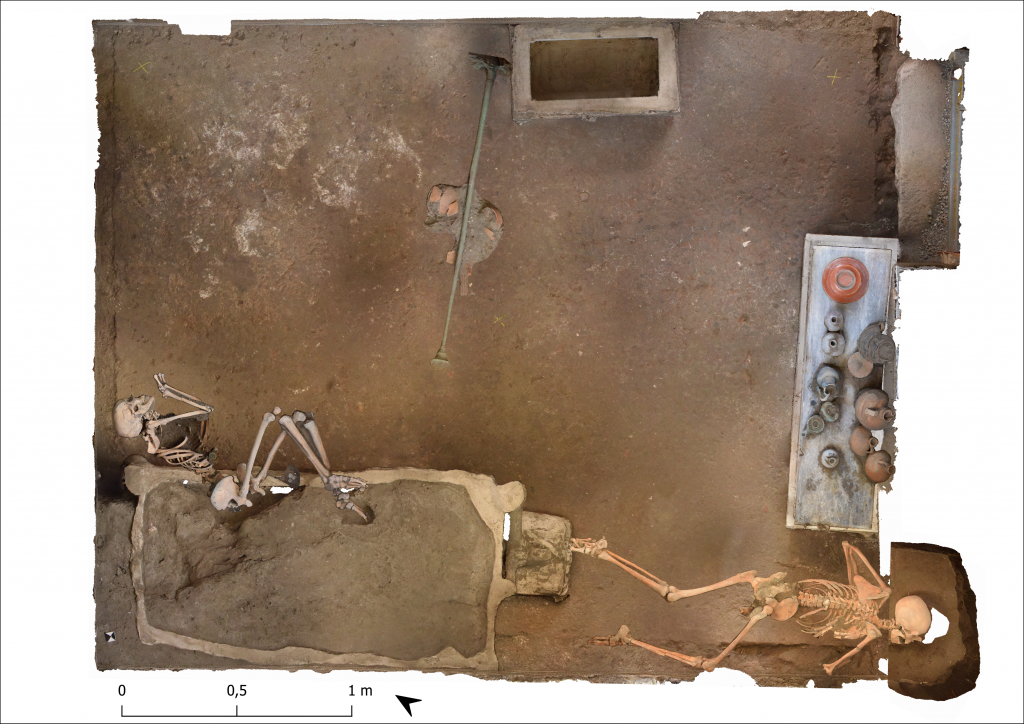

Room 33, following excavations. Photo: Archaeological Park of Pompeii.

The duo shut themselves in there to wait out the pumice that rained down on Pompeii during the eruption’s first day. But that pumice soon trapped them inside.

Although both parties likely died from the flows of lava, rocks, ash and gas that flooded Pompeii the following morning, an accompanying paper points out that they might not have died at the same time. While the 35- to 45-year-old woman expired in the fetal position, the 15- to 20-year-old boy turned up beneath a collapsed wall on the other end of the room.

Impressions left in the ash helped archaeologists map Room 33, which housed a wooden bed, an overturned stool, a locked chest, and a marble-topped table still scattered with homewares like glass jugs and a clay lamp. Its bronze candelabrum took a tumble during the calamity.

Aerial view of Room 33. Photo: Archaeological Park of Pompeii

Three hoards of gold, silver, and bronze coins turned up close to the curled-up woman. These proved the subject of intense rehabilitation and scrutiny. The cache, found scattered across one wooden box and the faintest evidence of two small cloth bags, totaled 34 coins dating from the Roman Republic through Imperial Rome, altogether valued at 696 sesterces—a decent sum, considering food for one year would have cost 2,160 sesterces. Only 10 percent of such nest eggs found across Pompeii amount to over 1,000 sesterces, the paper notes. Still, though, researchers studied the way this woman grouped her savings to learn more about which coins people spent and which they retained.

Archaeologists unearthing the female skeleton from Room 33. Photo: Archaeological Park of Pompeii

Beauty emerged in her cache, too, including a pair of gold and pearl earrings fashioned in the second-trendiest style of the first century. Pliny the Elder called them “crotalia,” based on the noise the pearls made when they collided. Four resplendent carnelian ovals also appeared, including one engraved with two hands joined around the caduceus, in a popular gesture from 68 C.E. expressing the desire for peace. And, a crescent-shaped pendant uncovered was a talisman known throughout Imperial Rome to protect babies and their mothers.