Art World

Archaeologists Discover That Easter Island’s Statues May Have Served a Surprisingly Practical Function

Their locations around the island likely have to do with a precious resource: fresh water.

Their locations around the island likely have to do with a precious resource: fresh water.

Caroline Goldstein

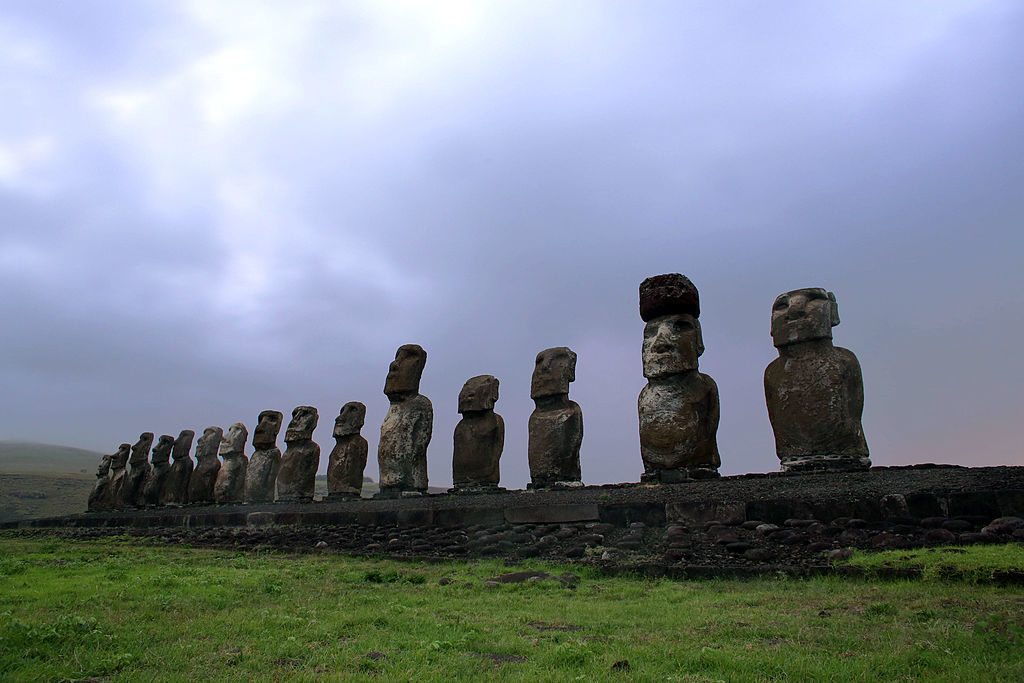

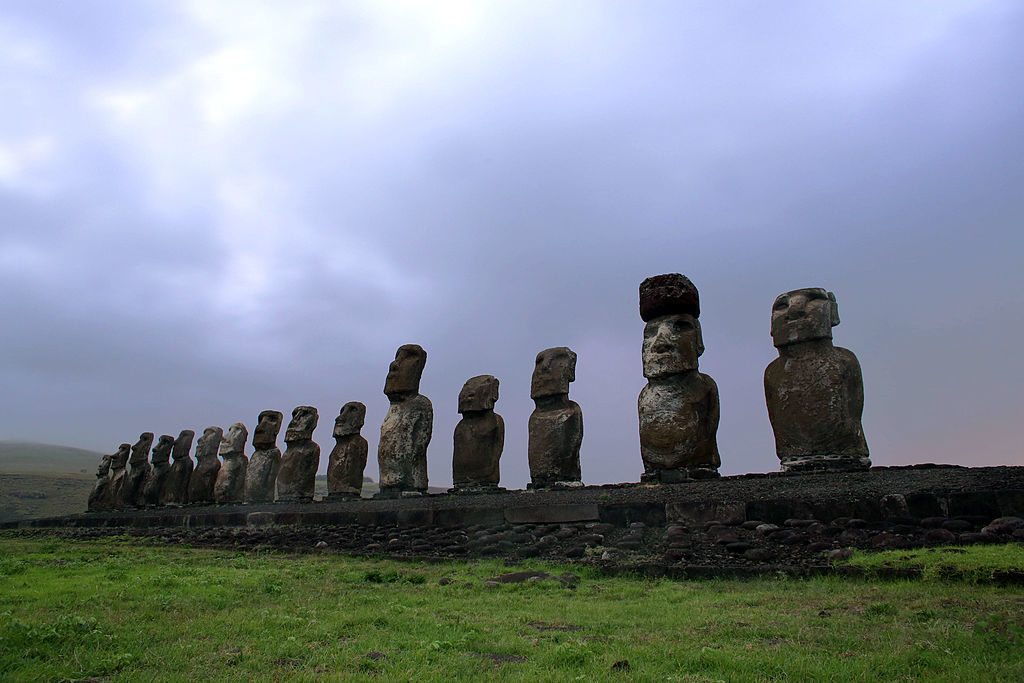

A new clue in the ongoing mystery surrounding the placement of Easter Island’s behemoth figures was revealed this week in the scientific journal PLOS One. According to archaeologists, the location of those hulking ancestral figures (moai) and the platforms they’re placed upon (ahu) is based on their proximity to fresh water sources—an exceedingly rare and precious resource. The figures had been seen as symbolic ancestral monuments, but it turns out they may have also served a more utilitarian purpose.

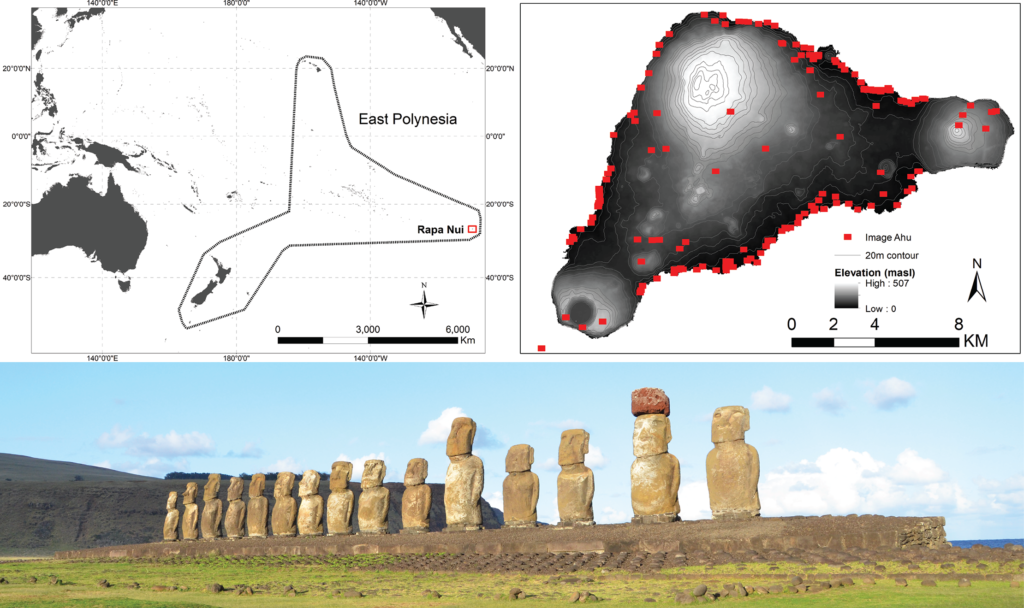

The researchers focused their attention on a quadrant of the Polynesian island of Rapa Nui containing 93 statues in order to support the long-held (though as yet unproven) notion that environmental factors are an integral aspect of the emergence of monument construction. The study ruled out the statues’ close proximity to gardens and marine resources as motivating factors in their choice of placement. Instead, it concludes that they may have been used to mark control of bodies of fresh water: “if Rapa Nui’s monuments did indeed serve a territorial display function (in addition to their well-known ritual roles), then their patterns are best explained by the availability of the island’s limited freshwater.”

(Top left) Rapa Nui in East Polynesia, (top right) locations of image-ahu on Rapa Nui, and (bottom) Ahu Tongariki with moai. Photo by R.J. DiNapoli.

Rapa Nui is home to more than 1,000 massive sculptural heads, and more than 300 megalithic platforms that are believed to have been constructed over about 500 years, a staggering achievement that the authors point out is even more impressive considering the “island’s ecological marginality,” which would have “greatly constrained the range of options available for subsistence to the island’s inhabitants.”