People

‘I Felt in Between Places’: Iranian Artist Arghavan Khosravi on Studying Art in the U.S., and Why She Paints Preoccupied Women

Khosravi recently debuted her first solo show at Rachel Uffner gallery.

Khosravi recently debuted her first solo show at Rachel Uffner gallery.

Noor Brara

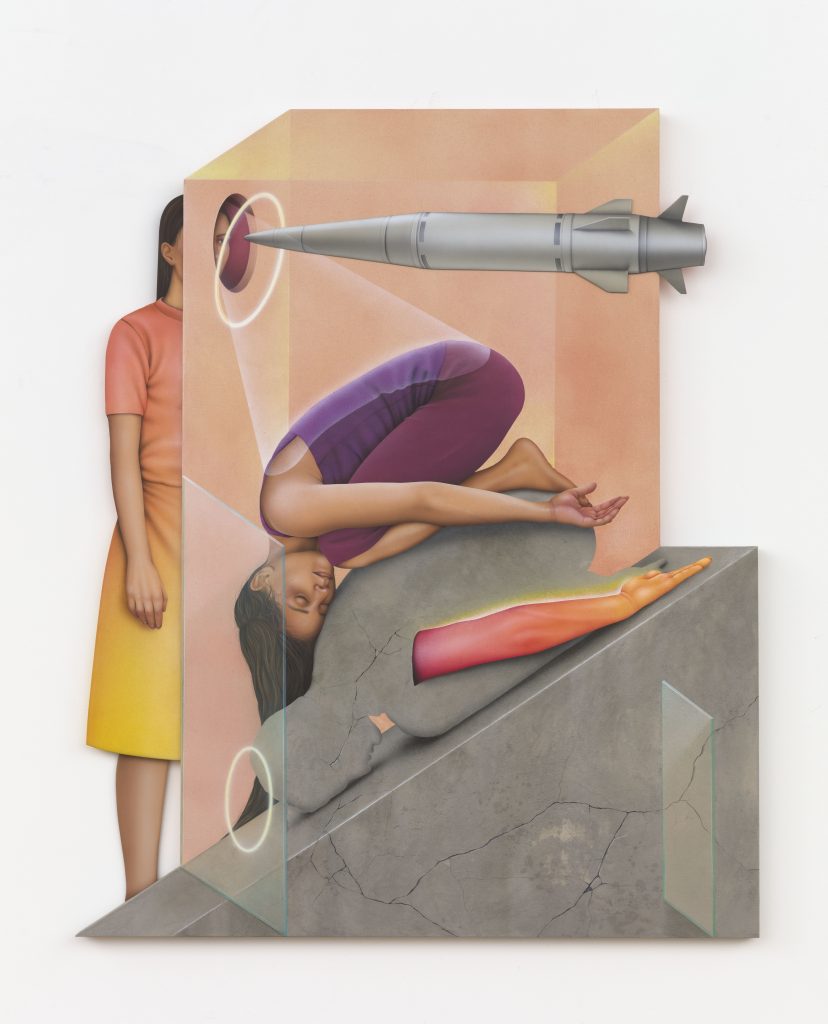

The U.S.-based Iranian painter Arghavan Khosravi’s sculptural, multi-paneled paintings capture the claustrophobia and disorientation of being split between worlds. In her critically acclaimed recent show, “In Between Places” at New York’s Rachel Uffner gallery—which was extended past its original end date several times, and finally closed in mid-June—women assume agency as they move through their daily lives, all the while preoccupied with looming concerns, represented by depictions such as a ball and chain, puppet strings, prayer rugs and other religious objects that seem to hang, quite literally, over their heads.

Each work is, Khosravi said, a visual representation of how she feels as an Iranian woman artist living in the U.S. who worries for her family, friends, and women more generally back home.

Khosravi sat down with Artnet News to discuss her incredibly successful exhibition, how she came to be a painter, and much more.

To start, I would love to know about your background. Where did you grow up? And when did you first have an inkling that art would be something you’d want to pursue?

I was born in Iran and I spent almost my whole life there. I grew up in Tehran. I think most kids are inclined toward art, to drawing and things like that. My parents were very supportive of me, in part because my father is an architect, so he already had that artistic gene. But in Iran, we need to decide at an early age what our majors will be, in high school. I thought my future career should be something more practical and art could be something beside it. I decided to study mathematics.

But during my last year of high school, I decided to switch to art. That was a bit hard, because what I had always prepared for in college was mathematics. But really, at that point I’d decided I should pursue something at the intersection of art and something practical. So I chose graphic design. I was a graphic designer for like 10 years, but then I thought that my passion and my ambition was really painting, so I came here to study painting in graduate school. So that was the first time, in 2015, that my main focus was painting.

What kind of graphic design were you doing before you made the decision to pursue painting full-time?

It was commercial graphic design for an ad agency. So like logo design, package design, posters, things like that. Some graphic designers are more inclined toward a fine-art approach, but for me it was strictly commercial, which I don’t regret, because it let me save money to pay for grad school.

Arghavan Khosravi, “Isn’t it time to celebrate your freedom?” (2021). Photo courtesy Rachel Uffner.

Makes sense. Tell me about how you felt when you were preparing to move to the U.S. in 2015 to paint. What was running through your mind as you were making that choice?

Because I didn’t have much experience, either academically or professionally, in painting, I thought it wasn’t a good decision to apply to grad school right away. So I applied for a one-year post-bac program at Brandeis University in Massachusetts. That one year helped me explore, and to have some time in the studio to see if I could make it as a painter. But back then, I still had this backup plan that, if I couldn’t find it in me to paint well, I would continue working as a graphic designer. But that one year helped me to make a real body of work, and to apply to painting programs. And the faculty there really encouraged me to pursue this, which gave me confidence. It was the green light I needed to take the risk.

And so then you landed at RISD.

My work really changed over the course of the two years I was there. For the first time, I could focus in my studio and come up with a creative process, which continues to evolve every year. For me, RISD really helped me find my voice and realize what I wanted to say in my paintings.

I remember my first critique wasn’t very good, which now I look back on and feel was ultimately very helpful because sometimes you need to destroy something in order to rebuild it and make it stronger. For a week I was very depressed [laughs]. I couldn’t touch my brush. But it helped me to change what I was doing.

So what came after the RISD program in terms of where you went and how you decided to approach your work? And how did that initial change begin to manifest?

Like many other emerging artists, I applied to some residency programs right after graduation, and I got a fellowship at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, which was a seven-month residency. That was really helpful for me because right after graduation you don’t have that much of a financial cushion to fall back on. I got that fellowship at a very crucial point, so I didn’t have to worry so much about things like rent, and I could just worry about my paintings. After seven months there, I actually could make some works for my first solo show in New York.

After that, I moved to New Jersey and became a member at the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts. But it was only a few months that I was there and then the pandemic happened and the whole studio shut down.

Oh god. How did you deal with that?

If I’m being honest, at the beginning it felt like the whole world was on pause and my very first reaction was relief. Like, “Oh, now I have time to reach all my deadlines.” But after a while it got frustrating. I had to bring all my studio stuff into my apartment because I didn’t want to go outside and use public transportation. In a way, I felt I could be even more productive because now my studio was right in my living space. I could work every day, seven days a week, and I could stay up until like 11 p.m. or midnight and keep working. But the downside of it was that I have always been part of a community, whether it was school or the different residencies, and I was always in conversation with other artists or visiting critics and curators. So, for a year, I was isolated by my own.

Arghavan Khosravi, “Patiently Waiting” (2021). Photo courtesy of Rachel Uffner.

Yeah, for sure. And your family?

My immediate family all lives in Iran. But my husband and his parents live here. So I didn’t feel too alone in that sense. But even before the pandemic, because of the so-called “Muslim ban,” I wasn’t able to exit the United States. Actually, I was able to exit, but I couldn’t reenter, so I preferred not to. So I couldn’t visit my family. In that sense, the pandemic travel ban didn’t affect my life because I was already banned to travel there. So… yeah. I don’t have anything more to add here. [laughs]

No, that’s fair. Tell me a bit about the show at Rachel Uffner. How did you come up with the work in it? And did you expect it to get as much attention as it did?

I made this body of work all during isolation in my living room. When I started working on these paintings I had a lot of uncertainty because it was the first time I was exploring a more sculptural approach to my work. I’d had some three-dimensional elements in my previous works, but this was the most 3D work I’d done. And because I wasn’t talking much with other artists or critics, at some point I thought, “Oh, maybe I’m going to the wrong direction.” Maybe my mind is too involved with three-dimensionality and things like that.

And I had some limitations physically. For example, I couldn’t work on very large boards in my apartment, so I came up with the idea to have multi-panel pieces. But it also felt like the right choice metaphorically, too… because it felt like I was in between places. I’m living here, my family is in Iran, so these fractured compositions kind of captured that. And it worked also in terms of the pandemic and how all of our lives were so disrupted.

They’re really evocative of how, I mean, just very simply, of how your mind can be in so many different places at once, especially as an international artist. And just how split that feeling can be, which I thought you illustrated in such an interesting way. I’ve never quite seen anything quite like that. Just even on a personal level, I can relate to that a lot. I’m curious, what are some of the reactions you’re hearing from people about your work?

Thankfully, I’ve heard some positive reactions and, like you mentioned, that it’s something some people haven’t seen before. I’m very glad to hear that. Because I don’t like to repeat myself. So it’s good to hear that it’s something new. In general it has been positive—or probably I’ve only heard the positive. [laughs]

If there’s anything you would like people to take away from the work, what would it be?

In general, I’m reflecting on my life experiences and memories from Iran. And in Iran, human rights issues, and women’s rights issues in particular, are in a really horrible situation. So for me, the starting point was reflecting on those memories and reacting to them. I hope that with the visual metaphors and symbols I use in the paintings, some people can feel that notion and, based on their own experiences, relate to the paintings in whatever way they’re able. Those are the main issues on my mind.

Arghavan Khosravi “Black Rain” (2021). Photo courtesy of Rachel Uffner.

I’m curious to know more about how the format of Persian miniatures has inspired your work and process.

Miniature painting, mostly Persian miniature painting, has always been one of my main sources of inspiration. And actually these more three-dimensional paintings somehow started from works that were based on miniature paintings… the architecture in those works. That gave me the idea to use shaped panels to emphasize some of the architectural depictions. The way architecture in those paintings is shown is much more like a “stacked perspective,” rather than separate vantage points. So that was how I started to think of paintings as 3D objects, not 2D surfaces.

In terms of the actual making process, the way I approach painting is very clean. It is very controlled, and I pre-plan everything. I mean, I tried different ways in school. I started with some more process-driven way of working, like pouring paint on the canvas and being more spontaneous. But I realized that, for me, it’s not helpful, and I get frustrated when things are out of my control. Maybe because a lot of things in my life are out of my control. So I prefer the painting to really be my territory. And I’m not good at making spontaneous decisions. I usually ruin a painting if I make a quick decision.

The way I paint is more like an additive process. When I want to start something new, I have a general idea about what I want to say, and then I go through a lot of source images, and those source images help me be more creative, to connect the dots. Because when I stare at a blank canvas, it’s intimidating. I can’t come up with any ideas. So I can think of myself when I look at all those source images that are from fashion photography or Persian miniature paintings or everyday life objects or pictures. I think of myself as a DJ rather than a composer.

Oh, I love that.

Because there are those existing images and I juxtapose them. And when I’m juxtaposing these images, this idea of contrast, or having imagery in contrast is always at the top of my mind. So whether it’s from Western imagery, or from a Western context into Eastern, like having Greek sculptures in an architectural scene that is appropriated from miniature paintings, I like the way it all comes together from different points of view. Or it can be about time… something from a more historic context against something more contemporary and so forth. Based on those images, I make several compositions, sometimes digitally. I come up with the color. And then, based on those, I make a one-to-one drawing, and the drawing is used as the base for the painting.

How do you know when a work is complete? Is it a gut feeling?

A gut feeling is exactly how I approach it. But when I think that my sketch is finished, I let it sit for one or two days and then go back at it. And if it feels that I was satisfied with the result and it gave me the excitement to start the painting part of it, then I know that the sketch is finished.

Arghavan Khosravi “The Suspension” (2020). Photo courtesy of Rachel Uffner.

That makes sense. I also wanted to ask you about something you said in an interview before, about how you wanted to steer away from the stereotyped portrayal of Iranian women as victims, or as oppressed. Could you speak to that a little bit more, in terms of portrayals of Iranian women and what people might learn about them from your paintings?

In general, I’m not interested in victimizing women and Iranian women, because I’m Iranian. And I do think they are in very oppressed situations, but I want to show that they have agency and they try, with activism, to change that. I’m not interested in just showing Iranian women as victims because there is this general idea through the media which sometimes is distorted or not quite accurate. I hope that with my paintings I can change that image.

How are you feeling about where you are now as an artist, about the success of this show and what it might mean for the work you’re doing now and will do in the future?

I feel good, because I put a lot of time and energy in for this show so whatever happens, I knew that this is the best I could do. And the feedback I’ve received was reassuring because, as I mentioned, I made these works in isolation. So it’s encouraging to know I can keep being more experimental with some sculptural works and try different things. I don’t have to repeat myself to feel successful, which is good because I like to challenge myself.