Art & Exhibitions

The Most Subversive Work at the 9th Berlin Biennale Is a Secret Intelligence Agency

We spoke to Armen Avanessian, the writer and theorist behind the project.

We spoke to Armen Avanessian, the writer and theorist behind the project.

Alyssa Buffenstein

Some critics of the 9th Berlin Biennale perceive the DIS Magazine-curated exhibition to be apolitical, but for the past three weeks, one project has been proving that criticism wrong. DISCREET is a collaborative project that set out to build an “Intelligence Agency for the people,” an organization that could learn from, but work against, opaque agencies like the NSA.

Fifteen participants were selected based on individual project proposals for the three-week long workshop, on topics from e-waste to immigration patterns. Together, they took part in tours, workshops, and intelligence-collecting missions, like being sent outside of Akademie der Künste—where the green-screen-enclosed set and workspace, designed by the critical architects of Studio Miessen, was based—on missions like getting strangers’ home addresses, or convincing tourists to come inside to see the Hito Steyerl installation, part of a project called The Spy School by Tea Tupajić.

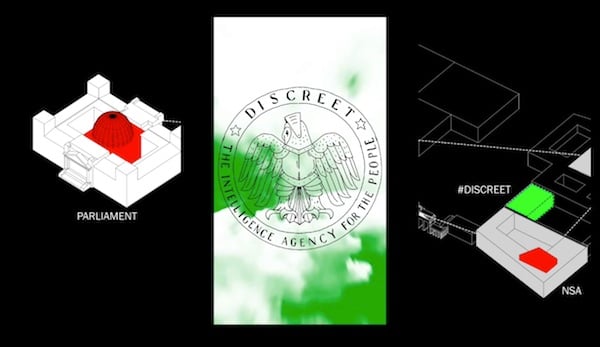

DISCREET – An Intelligence Agency for the People. Still from trailer (2016). Image courtesy of Armen Avanessian/Alexander Martos ©Christopher Roth.

When DISCREET was at work, and while they brought in guest speakers, like hackers and activists, for training sessions and “Insecurity Counseling,” a live stream was viewable online, and visitors to their headquarters at the Biennale could stop in and observe in person. If a visitor was so inclined, they could also use the Call a Spy Booth, an installation by the Peng Collective set up as a part of Discreet, and call one of over 30,000 leaked telephone numbers belonging to real spies around the world.

DISCREET was commissioned for the 9th Berlin Biennale, and lead by the writer and theorist Armen Avanessian and Alexander Martos in collaboration with filmmaker Christopher Roth. Avanessian, who is on paper a philosopher and political theorist, spoke to artnet News on the last day of DISCREET’s work to get us up to speed on what the project was able to accomplish in its short time.

After only three weeks of collaborative work, there are few concrete answers, but sitting in MINT, Débora Delmar Corp.’s juice bar installation, Avanessian explained his interest in DIS and their generation of digital natives, what it takes to begin to build a real intelligence agency for the people, and why he thinks that might be the only way to effect political change.

Still from DISCREET trailer (2016). Center graphic depicts mock-up of DISCREET’s physical workspace. Image courtesy of Armen Avanessian/Alexander Martos ©Christopher Roth.

What were DISCREET’s original goals?

DISCREET is an experiment, but the goal to build this intelligence agency was always real. I think it’s a necessary institution, but I can’t do it alone, so we invited hackers, financial experts, and very different kinds of people in order to see what happens. It was the idea that, under the gaze of the public, not top-down, but together with others, we were going to work together on the framework, rules, targets, goals, different departments, and orientations of this agency. We also wanted to provide a kind of matchmaking; for example, if someone is a hacker, he might need some financial advice about the blockchain. We can help each other.

How did you create this platform?

I think art is important for giving people a space to talk to each other. What kind of stage can one build so that people who might find answers to these questions, and provide solutions, can talk to each other?

So we built a strange setting, by Markus Miessen and Studio Miessen, that is at once safe, and helps us to talk to each other with some kind of intimacy. But on the other hand, it is transparent, not hidden away in the desert in a top-down way. So the whole setting is really trying to play with the tension between transparency, the basis of democracy, and secrecy, how intelligence agencies work.

Why is an intelligence agency for the people necessary?

Data and information are the most important resources of the 21st century, and we are actively, constantly producing information. We are confronted with an excess of data. Like with every media revolution in the past, all of a sudden we have so much new data that we are freaking out. We have to grasp it and find a new way of ordering our society. So intelligence agencies have an incredible potential, if they would not just work together with Google, or declare a war on terror, or spy on the people. Intelligence agencies provide information that leads to change. Mostly in an evil way, but wow, it’s a technique that we should learn.

DISCREET logo overlaying a map of Akademie der Künste, the German Parliament, and the American Embassy, where the NSA tapped Angela Merkel’s cell phone. Still from DISCREET trailer (2016). Image courtesy of Armen Avanessian/Alexander Martos ©Christopher Roth.

How did you begin to conceptualize DISCREET’s intelligence agency?

It was pretty clear from the beginning that we wouldn’t work for three weeks and then know the answers. We are still discussing very basic steps, like whether this is an agency, an institution, a school, or a company. We thought about being a company; maybe that is a better way to gain information and access to certain positions. A lot of things in the intelligence business are given away to private companies.

We discussed whether we needed a global network of informants, and asked who the sovereign is for whom we want to provide information. We discussed what the people can learn from intelligence agencies like the NSA, and how we could give them another, democratic, agenda.

Why do this in the context of art, rather than philosophy or theory?

I would feel uncomfortable to say it’s only an art project, and I don’t want to be put in the “art” box that might exclude this from the realm of politics. I wanted to do this as a performative artistic project that could achieve certain goals I couldn’t achieve elsewhere. In academia, I might be obliged to do a seminar on sovereignty from, let’s say Machiavelli to Hanna Arendt, but that doesn’t necessarily help you with the NSA.

In an art context, usually a theory person like me is asked to write a catalog text about why a certain work of art is so critical and good, or to provide a short theory conference. I’m doing neither, I’m trying to really be an artist, and to appropriate the tools and knowledge of art people to find out about how the distribution of images and information today works.

I hope DISCREET doesn’t fit into the realm of contemporary art; it’s what I would call post-contemporary art. Instead of strengthening the existing institution of art by criticizing them, it’s inventing a new one. It’s using the art world to do something that cannot be done in a political think-tank, nor in a political theory seminar, and at the same time hopefully works as an alternative to the usual procedures of contemporary art.

DISCREET – An Intelligence Agency for the People. Still from trailer (2016). Image courtesy of Armen Avanessian/Alexander Martos ©Christopher Roth.

How does DISCREET fit within the Berlin Biennale?

I’m interested in people like DIS, and this post-internet generation. I’m not convinced in how this generation thinks politically, but I’m intrigued by their tacit knowledge of technology, the internet, how they deal with attention, distribution of images, memes, and so on. Artists of this age are criticized a lot for giving in to the market, but I’m interested in their capacity for providing something else than the usual, pseudo-critical contemporary art market.

I think there’s a generational paradigm shift going on, and we don’t know yet where the criticality or subversiveness is. Digital natives like DIS and their generation have tools, knowledge, and practices that I—being an academic of a certain age—don’t have access to. But I have a certain political interest and I want to give it that spin. That’s where the future is, if we manage to change things for the better.