People

Is Arne Glimcher’s New Tribeca Gallery a Vanity Project? ‘Maybe It Is,’ He Says

After 62 years in the art business, the Pace Gallery founder just wants to show what he likes. He hopes you like it, too.

After 62 years in the art business, the Pace Gallery founder just wants to show what he likes. He hopes you like it, too.

Katya Kazakina

Since opening Pace Gallery at 125 Newbury Street in Boston in 1960, Arnold Glimcher, known informally as Arne, has become one of the most powerful art dealers in the world. Based for many years in New York, Pace is now a mega-gallery, with outposts in Los Angeles, London, Hong Kong, and Seoul. It represents 122 living artists and estates, the most among its rivals Gagosian, David Zwirner, and Hauser & Wirth.

Over the past decade, Glimcher, 84, has passed the baton to his son Marc, who oversaw the construction of Pace’s 75,000-square-foot headquarters in Chelsea and branched out into new technological frontiers like NFTs as well as new models, like the experiential-art emporium Superblue.

So it was surprising when the elder Glimcher announced that, rather than retire or rest on his laurels, he would launch a new initiative of his very own: a Tribeca project space called 125 Newbury. A shout out to Glimcher’s early years in Boston, the gallery is 15 minutes south of Pace’s Chelsea hub, in the burgeoning epicenter of New York’s art scene.

The art world came out in force for the opening. There were artists Jeff Koons, Julian Schnabel, Lucas Samaras, and Robert Gober; collector and longtime client Linda Macklowe and gallerist Mary Boone; museum honchos Max Hollein and Michael Govan; and young stars Loie Hollowell and Julie Curtiss. Located on Broadway, one block south of Canal Street, the 3,900-square-foot ground-floor space used to be the home of home-decor hub Pearl River Mart.

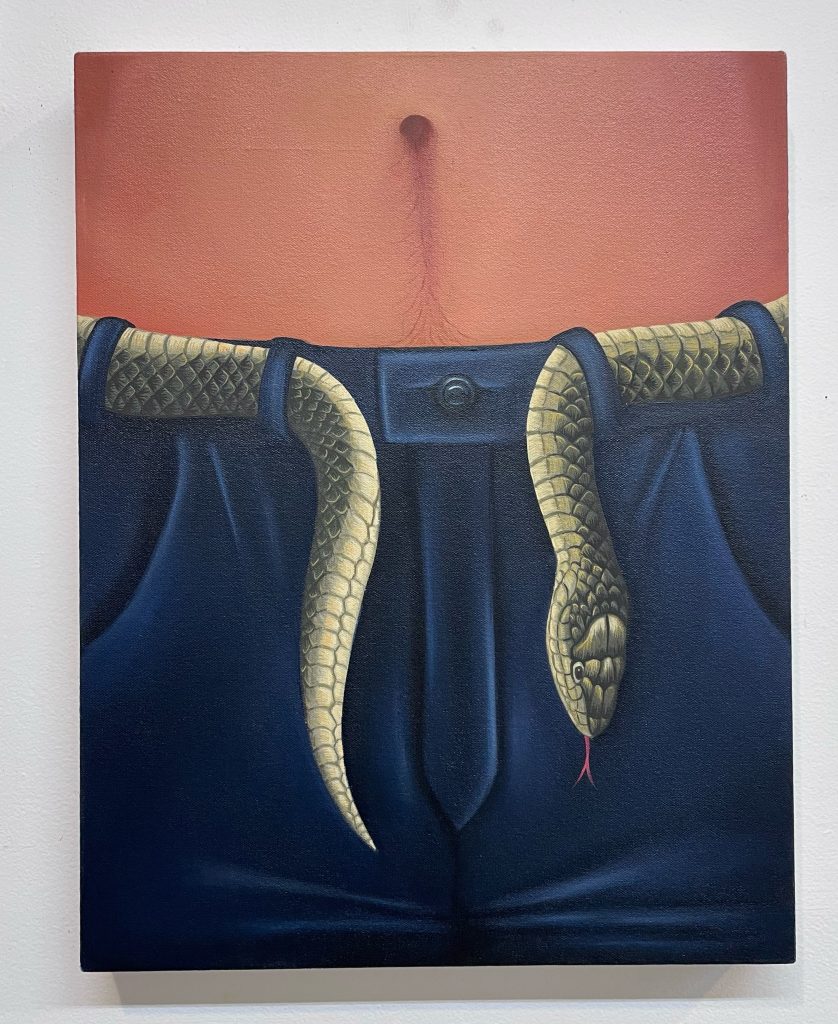

Julie Curtiss, The sinner (2022). Courtesy: 125 Newbury

The opening show is titled “Wild Strawberries,” after Ingmar Bergman’s 1958 film and a nod to Glimcher’s career in Hollywood, where he produced several films in the 1980s and directed Mambo Kings in 1992.

The exhibition includes sculpture by Kiki Smith and Lynda Benglis, videos by Alex Da Corte and Zhang Huan (in the latter, the artist sports a raw meat suit). There are two new figurative paintings by Curtiss and many works by Samaras. It’s a compelling if somewhat disturbing array of mediums, connected by in-your-face materiality.

I spoke with Glimcher the day after the opening. Below is an edited version of our conversation.

Congratulations! How are you feeling?

I’m happy because people love the exhibition. We had about 700 people. They waited in line for two and a half blocks. It was so embarrassing! It’s not a really big gallery, so you could only let so many people in at a time to keep the art safe. But everyone was in a good mood and nobody was angry that they had to wait.

The show is a really surprising mix of the new and the blue-chip, but less blue-chip than I would imagine.

I don’t care whether it’s young or old. It’s just what interests me. I’m interested in ideas and how they’re transferred. I had been thinking for quite a while about doing this exhibition based on the idea of the line between threat and seduction, the way that something becomes attraction and repulsion. So think about Paul Thek and Lucas Samaras. And we can think as far back as Rembrandt’s Slaughtered Ox, which is a painting I’m sure was very hard for people to look at until they saw how beautiful it was. That’s the idea that has interested me most of my life.

Are works for sale?

Some are for sale, some are not. Some are borrowed. I showed Paul Thek in the ‘60s. So I had to borrow those back, because the pieces I want, you can’t find. I borrowed them from an institution.

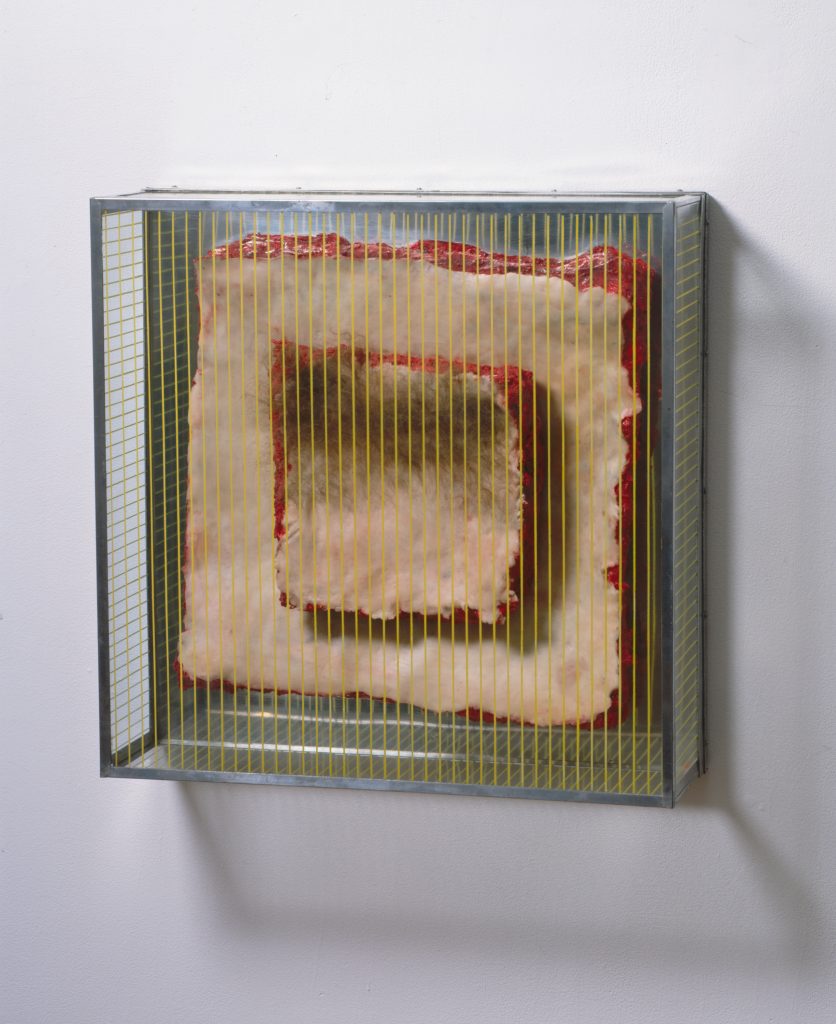

Paul Thek, Untitled, from the series Technological Reliquaries (1964). Courtesy: 125 Newbury

Pace has so much real estate in Chelsea and beyond. Why did you need to open your own space?

We don’t have enough real estate in Chelsea, that’s the sad part. I used to do exhibitions like this every year, every other year at Pace. But there are so many important artists who want exhibitions and so now it’s mostly one-person exhibitions. This gives me a little space to experiment, to do what I want to, have some fun.

Why Tribeca?

I’ve been in Midtown and Soho and Chelsea. I thought it would be interesting to be in a new neighborhood. I liked the idea of being on the street.

For works that are available, what’s the price range?

That’s not what my space is about. I wanna make the shows I wanna see. If we sell something, that’s great. If we don’t sell anything, that’s great too.

What if somebody thinks that this is a way for Pace to lure artists who are with other galleries away from those galleries?

If they think that, they’re just perverse. None of the dealers objected at all to artists showing with me.

It is a project space. I can do what I want to and I can ask artists who are affiliated with other galleries if they wanna participate in my shows. And so many artists were so gracious and made works for the show. Artists like Julie Curtiss and Kathleen Ryan.

Forgive me for being a little skeptical. But the art market is a pretty cutthroat business and yet you are just totally free of any pragmatic considerations? Is this a loss leader? It just doesn’t compute.

I’m doing this for myself and I hope that it will benefit the community. This is a completely different operation from Pace. The last 10 to 12 years, it has been Marc and that’s been wonderful. I want to do something different.

I was curious if you would ever show works from your personal collection?

No, no, no, no!

No, no, no, no?

I could see if I was doing some kind of a theme exhibition, and I had something in my collection that fit in with it, I would show that, but that wasn’t the case now.

But, you know, I’m leaving myself sort of wide open, very nimble. I do not even have this season’s schedule filled. I’m only gonna do four shows a year, maybe five. They’re gonna run between two and three months apiece. This is a gallery without a program. I think I’ll get a program, but I don’t have it yet. And I’m just gonna respond to what’s exciting to me now.

“Wild Strawberries” exhibition installation view. Courtesy: 125 Newbury.

How do you respond to people who see this as a vanity project?

Maybe it is. If I can’t afford to do this now, when will I be able to do this? I’m like a kid. I want to do it.

What are you hoping to add to the ecosystem with your shows at 125 Newbury?

I’d like to think what we’re adding to the system is discrimination and excellence. I think that’s missing. I think people are now accepting everything that anyone makes as art. There’s a lot of incredible mediocrity. People are settling for that. I can’t settle for that. I never have my whole life, and I’m certainly not gonna begin doing that now. I want to show things that are of value and quality.

I just saw a Twitter post by Jerry Saltz, about “a recent critical tic is that any art from between around 1961 to 1989—being rediscovered now—is automatically good. Some of it is. A lot was forgotten for a reason.”

I absolutely agree that many forgotten artists are forgotten for a reason because they aren’t as good as the artists that are remembered.

Look how many artists there are today. There are more artists in the world than have ever existed. A lot of these are going to be lost in the dust of time. Do you think they’re all gonna be resurrected?

It’s great to see the works by Paul Thek in your show. We don’t get to see them that often. Lucas Samaras is also represented in depth.

Samaras’s early works, those books covered with pins and frightening objects—people were terrified of them. I showed Paul Thek in the 60s at the Pace Gallery.

And then what happened?

Paul got very heavily into drugs, moved to Europe, became infected with AIDS, and we just didn’t see each other very much. I was busy in New York. He was not here anymore. But I think of all those shows, the most important one was in my gallery. The work in the [Museum of Modern Art] called Hippopotamus Poison, you know, that was in one show. But they were very, very hard to sell. Everybody thought I was crazy showing them.

Hannah Wilke, S. O. S. Starification Object Series (Performalist Self-Portrait with Les Wollam) (1974). Courtesy: 125 Newbury

Do you think younger artists approach their careers very differently now, with more pragmatism?

Well, the time is so different. As you know, these artists have a market out there for their work. When Rothko was painting, he hardly sold the painting. When I was showing Paul Thek, I hardly sold the Thek. I hardly sold the Samaras. It was all very difficult. So they’re living in a more privileged time financially, but they’re also living in a more difficult time psychologically, because everything they make is being scrutinized. Everything is so public. So in a way I feel very sympathetic and tender towards young artists today. I think it’s one of the most difficult times, at least in my history, for a young artist.

A lot of people have turned to Instagram to discover artists. Have you?

No. I’ll have an artist who says to me, “I saw this young artist friend of mine who lives nearby, who makes really beautiful work.” Or I’ll have a friend who’s a writer, and they’ll say, “Oh, I just visited this artist in the studio,” and then I’ll go visit.

I love going to artist studios. I see someone at least every week. I’ve seen some interesting young people in California, in New York or Brooklyn or London.

What’s next?

I was working on this show for about a year, but I was thinking about it for about 10 years, and I have other things I’m thinking about. Fasten your seatbelts!