In these turbulent times, creativity and empathy are more necessary than ever to bridge divides and find solutions. Artnet News’s Art and Empathy Project is an ongoing investigation into how the art world can help enhance emotional intelligence, drawing insights and inspiration from creatives, thought leaders, and great works of art.

In the land of crossover culture, there are few artists as knowledgeable as Futura and Daniel Arsham.

Futura (born Leonard Hilton McGurr) made his career by becoming an enormously influential graffiti artist in the 1970s, painting works all over New York’s subways, and, a decade later, exhibiting work alongside Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and Kenny Scharf.

Arsham, meanwhile, collaborates frequently with major brands like Dior and Rimowa, and was recently named Creative Director for the Cleveland Cavaliers.

We sat down with them to talk about their unlikely friendship, how the art and design worlds view their work, and why empathy should—or shouldn’t—play a role in art-making.

How did you meet?

Daniel: I think it was probably through Timmy, right?

Futura: I’m glad you started there, because I was just thinking, “I guess I know Daniel through my son, Timmy,” who is 36, and that’s within Daniel’s demographic. You know, we’re all looking around within our own demographic as we come up as well as those inspirational folks who are ahead of you a little bit, and then of course people coming up right behind you. Daniel knows my son way better and they’ve had more experiences together, but that’s cool because Daniel to me was just an artist I respected before I knew him.

Daniel: I met Timmy through Ronnie Fieg at Kith. We’ve been on a number of trips together. I knew Futura as an idea and as an artist before I met him personally, and for a long time I actually didn’t know that they were related. I had heard Futura mentioned in the context of some Kith event—actually I remember having a long conversation with you, Lenny, when we opened the Kith Lafayette store. You did a Nike collab and at the dinner you were doing some drawings on the boxes and we all had these linen napkins, and I asked you if you would do a drawing on the napkin. I have that napkin with your drawing on it framed in my studio. But yeah, I knew Lenny’s work from the time I was a teenager. I was never really into graffiti in the way that his universe sort of encompassed, but I always respected what I saw here in New York and when I moved up here, he was this kind of legendary figure both in that and also in his streetwear.

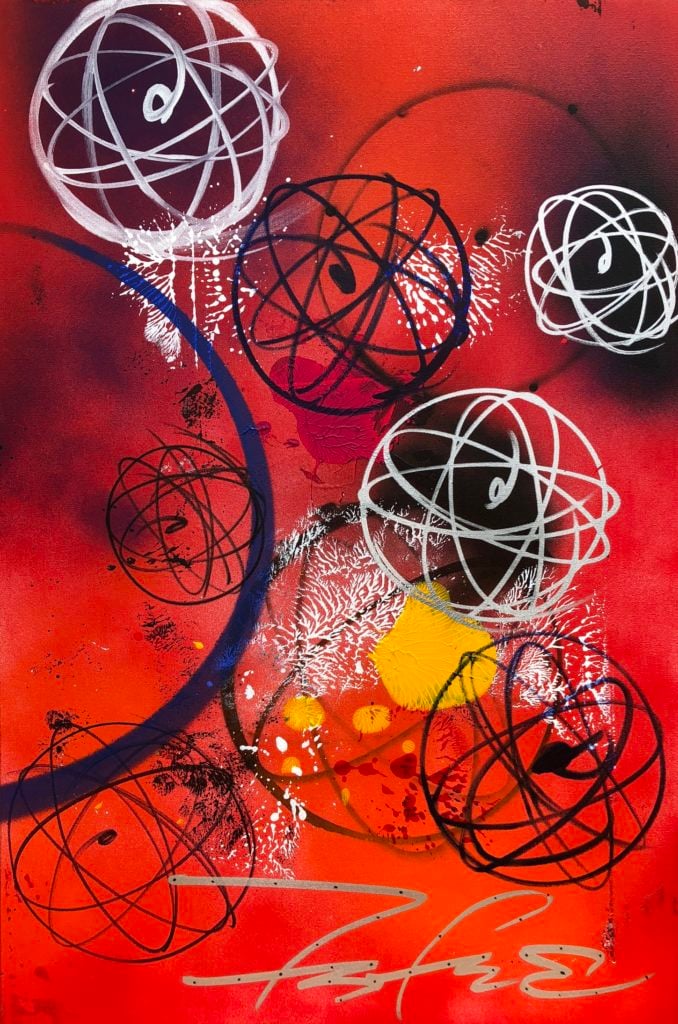

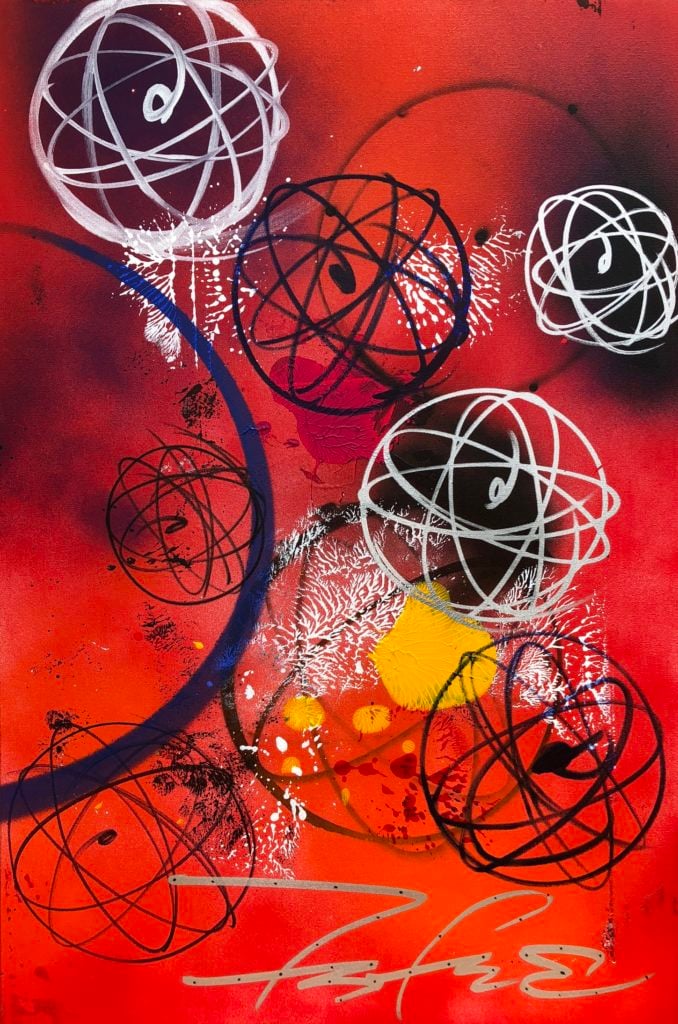

Futura, Rambo (2017). Courtesy of artnet Auctions.

What’s something you’ve always admired about the other’s work and process?

Daniel: Lenny, you’re not an old guy, but you’re not super young either [laughs] and I think watching the arc of your career evolve over the years has been inspiring. I mean, you started doing what you’re known for now probably in the early ’80s or late ’70s, and to have a career that evolves so much over that sort of time is amazing. I’ve tried to bring my work outside of a museum or gallery context whenever I can, but it’s never achieved what Lenny’s has in that sense.

Lenny: Daniel’s stuff is amazing because what you do, Daniel, is you capture these sculptural pieces in all these moulds you make and it’s sort of like an Apple product in a way. It’s always really amazing with the tech and the design; it’s all very thoughtful work and it’s architectural and really beautiful. I’ve always gravitated towards Daniel’s stuff. One day I’d like to see super-big Daniel pieces. Side-of-rock type stuff. Mount Arsham. I’m with that.

The art you both make is sort of amorphous in terms of form and categorization. What, in your eyes, is the difference between art and design? How do you feel about art-fashion collaborations, and those collaborations becoming increasingly ubiquitous?

Daniel: The first crossover collaboration I did with Adidas was in 2012 or 2013. I remember at the time, even though it wasn’t particularly new, a lot of my gallerists and a number of collectors close to me were very reticent about collaborating with such a commercial entity. Their position was sort of like, “Are you comfortable allowing this company to use your work to sell their products?” And I’d seen Futura and KAWS and tons of different artists doing this and my whole thing was, “How can you not see that I’m actually using them for their reach to millions of people who aren’t part of the art world and don’t go to museums and galleries every day and don’t have access to this kind of work?”

The other thing that always confused me is, this is nothing new. Warhol was doing this in the ’60s, and he was doing television commercials in the ’80s for Sony. It’s the same people that are collecting this universe of work and are following the Warhol canon, so I really didn’t see anything necessarily problematic there.

Daniel Arsham with his site-specific installation Moving Basketball (2019), at Rocket Mortgage FieldHouse. Courtesy of the Cleveland Cavaliers.

Lenny, what would you say about that liminal space between art and design?

Lenny: It’s funny, those two words right? Art and design. That was a famous high school in New York City—A&D. I graduated in ‘72. My New York City education—I went to public school—was always of that era and you can imagine the kind of stuff that was floating around. By the time I graduated, graffiti was already on the subway system and around the city itself, but I couldn’t get into the Art and Design High School. They rejected whatever little portfolio I had, which wasn’t very much because I wasn’t really an artist. But I loved design. I guess I became an artist, but my real love was always design and the perfection of logos… IBM, Coca Cola. Those were the things I grew up on, with their simplicity, and there was a real beauty to things like gas company logos before Warhol introduced certain things that are now deemed to be iconic, i.e. the Brillo boxes and all these other things.

But even the Brillo boxes were branding. The Campbell soup cans were branding. And graffiti was nothing more than that, even though at first I didn’t get it. Graffiti was our own invention of branding. We’d say, “Oh, there’s a product on that wall.” Or, “Okay, within our subway system, they’re selling that product in that advertisement.” And the system makes money off of that company. So we thought, why can’t we just write on the walls and advertise ourselves? So that was the essence of what we were doing. Even when Peter Max was doing ads on the subways and buses in New York City, he was being paid to do that. He wasn’t gifting anybody his work.

Futura 2000. Photo courtesy BFA and the artist.

Here’s a question we always ask: if you had to trade jobs for a day or body swap, what’s the thing you’d most look forward to?

Futura: Just knowing everything. If I could be Daniel for the day, I’d just walk around his operation knowing everything. And that comes with the fact that I’m Daniel in this scenario. I’d just be impressed with how I was handling everything, and his medium and his creativity and how he translates that to production. It’s really the skill of his process. I don’t have any knowledge of that stuff.

Daniel: If I was Lenny, I’d probably want to be Lenny in 1983. I’d go back in time and be out at night with a bunch of people… go to the Mudd Club and hang out with some friends and be a part of that New York era. I moved to New York in 1999 from Miami, and by that point, it wasn’t what it’s like today, which is sort of like a mall. But it wasn’t what I imagined to be then either, like how it was in the’80s, which was a little bit more like… I don’t know, grit is the obvious term, but maybe wilder and more open. The opportunity felt different. The East Village in 1999—I went to school at Cooper, so Astor Place and that whole area was so different back then. I’d just go back and be you in that era, Lenny.

Futura: Did you ever spin that Cube around?

Daniel: Yeah, of course. [laughs]

Futura: Yeah, okay. You’re good. If you spin the cube, you’re good with me. Wow, Cooper… I got rejected from there, too.

Daniel: Having gone through that education, which is a very rigid, formal education, you’re better off not having gone through that, I think, for the type of artist that you are, Lenny. I don’t know if it would have benefitted you.

Futura: Well the thing is, when I didn’t get into those schools, I went into the military. I had all these cool ads that I’d made and those institutions were just like, “Nah.” Unfortunately, they were all very militaristic, because that was a big thing I used to see—you know, there was still a war going on when I was a high school senior in ‘72. So most of my portfolio was defense contract ads and tanks and plans, and they just thought I was too out there. I remember one guy was like, “You know man, I don’t know where your head’s at, but you know we’re killing children over there right?” And I was just like, “Oh ok, sorry.” So that’s on the real.

Daniel Arsham. Photo by Guillhaume Zicarelli.

We’ve been talking a lot these days about whether art needs to occupy some moral ground, or if it has an obligation to bring people together. How do you feel about that? What, in your eyes, is the role of art today, if it should have a role at all? Do you think about empathy in your practice?

Daniel: I think there are two types of artists. There are the kinds that make work not necessarily in a vacuum, but the work is more made for themselves—it’s an outward expression or a way to understand the world around you. And then there are other artists whose work is a kind of interpretation of existing times that has the express intention of communicating some sort of tangent that people aren’t really seeing.

I’m in the latter category, so my work is really about trying to understand and parse through this strange existence, and then to reveal things that are just outside of our everyday experiences. Most of the work I make involves using things that are already around that reference ancient Greek or Roman works, or manipulating the surface of architecture and playing with people’s understanding or conception of time. These are all quite simple concepts, actually, and the power or empathy that can come with them is about revealing something that is quite surprising to find that you already know it. It’s a thing you recognize, but there’s something a little bit off with it that can allow you to experience your own everyday, just in a different way.

Lenny: Last year, in the midst of our social unrest, I was asking myself, “Do I choose to be a kind of crossover artist once again?” Art, design—and okay, now politics? For me, no, not so much. Empathy is important in life, but I wouldn’t say it’s a huge factor in my work. I’m never going to be on a soapbox talking about stuff. I have an opinion, certainly, but I don’t feel it’s appropriate with what I’m doing. I’d rather just be Switzerland. It seems harder now to talk with people. I want to respect everyone, but I guess if someone’s stuff is really kooky, I can’t be part of the discussion and I can’t engage with them, but, I’m open. People have to be where they want to be. So that’s just to say that the Jenny Holzers and the Krugers and Swoon—it inevitably feels like it’s female artists who are making the protest art, which makes sense and I applaud all that of course.

And from our side, I don’t know who is really the political artist representing this culture so to speak. That occurs on a local level, and you know there was a guy, Blu, from Italy. I don’t know what happened to him, but he was, to me, one of the most powerful artists on the planet at one point. This guy was amazing—he’d go into places and paint things that you just don’t paint there, like he went to Bogota, Colombia and he made a whole mural about cocaine and it being like crushed skulls or something. It was amazing. He set the bar really high. So yeah, I have an opinion and I think certain things are incorrect right now, but that just won’t be evidenced in my work. That’s just not for me to speak on it.

Installation view, “Futura 2000” at Eric Firestone Gallery.

You both have mini-anthologies either out now or coming soon of memorable quotes of yours pulled together from over the years. What’s something you want people to know about what it is to be a creative person? A piece of advice, maybe something from your book?

Futura: There was one quote that I think really holds up, which is that it costs money to be independent. And I think it’s really about not taking money from other people. Not biting into the bait of someone coming and offering you a check. Because if you thought about it from any self-confidence basis of what you’re doing, there’s gotta be more than one person with a cheque. It’s a chess game, you reverse engineer stuff. I think I just opted out of someone controlling me. Or it’s really just to say, be wary of people who come with an envelope… or even a smiling face.

Daniel: There are a couple things I think about when I’m making work. Generally, I first make work I want to see exist in the world—that’s the prime drive behind things. But a similar sentiment to what Lenny just said is, the things that you say no to, in the end, will actually be more important than the things you say yes to. These opportunities that come up, the ones that you reject—or frankly the ones that reject you, if you’re talking about Lenny not getting into Cooper—you have look at those as as much of an influencing factor as the ones that you accept.