Across the United States—and the rest of the world—images have become central to the ongoing protest movement that has gained strength since the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. Artists have painted “Black Lives Matter” banners on streets so large they can be viewed from space, demonstrators have covered the fence of the White House with vivid protest art, and statues of Confederate figures have become a central rallying point.

To help us better understand the current moment and the role art and artists have to play in it, we asked academics who have studied artistic responses to previous rebellions and Civil Rights movements to provide context for what we’re seeing now. Read on for their perspectives on how artists of the past contributed to and helped shape historic moments of change.

Casarae L. Abdul-Ghani

Professor of African American literature at Syracuse University

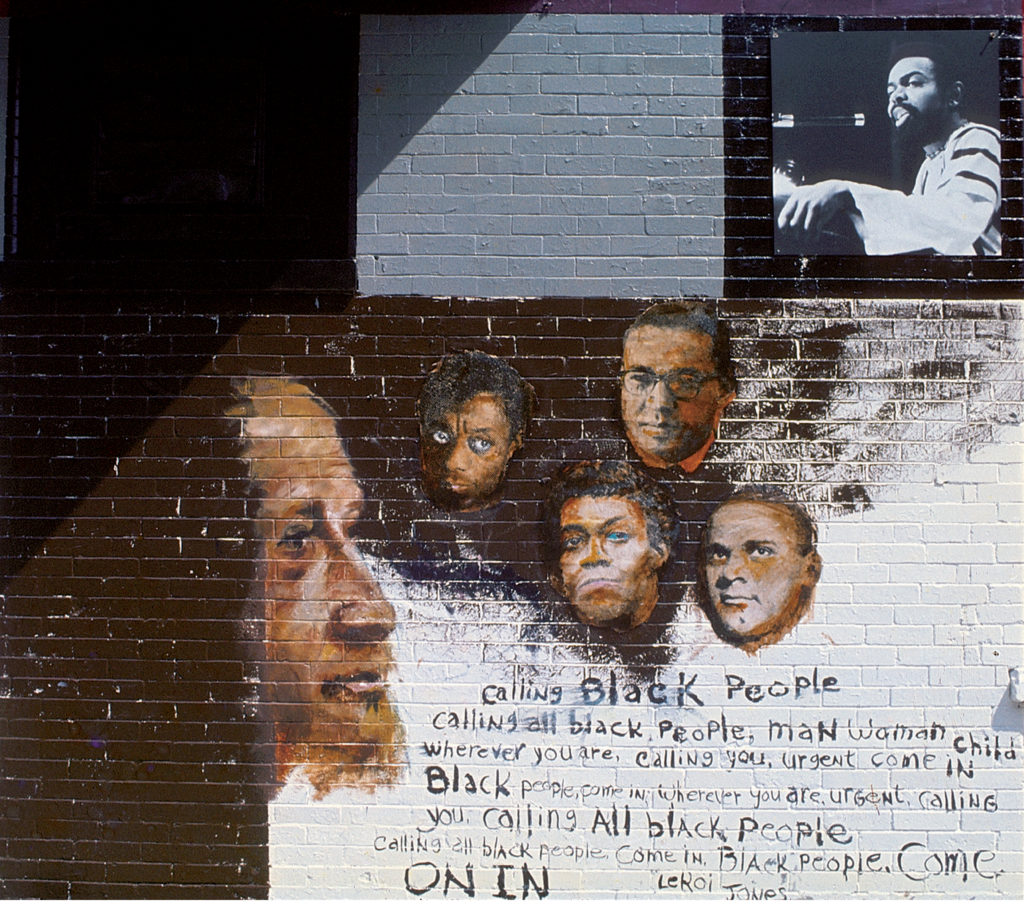

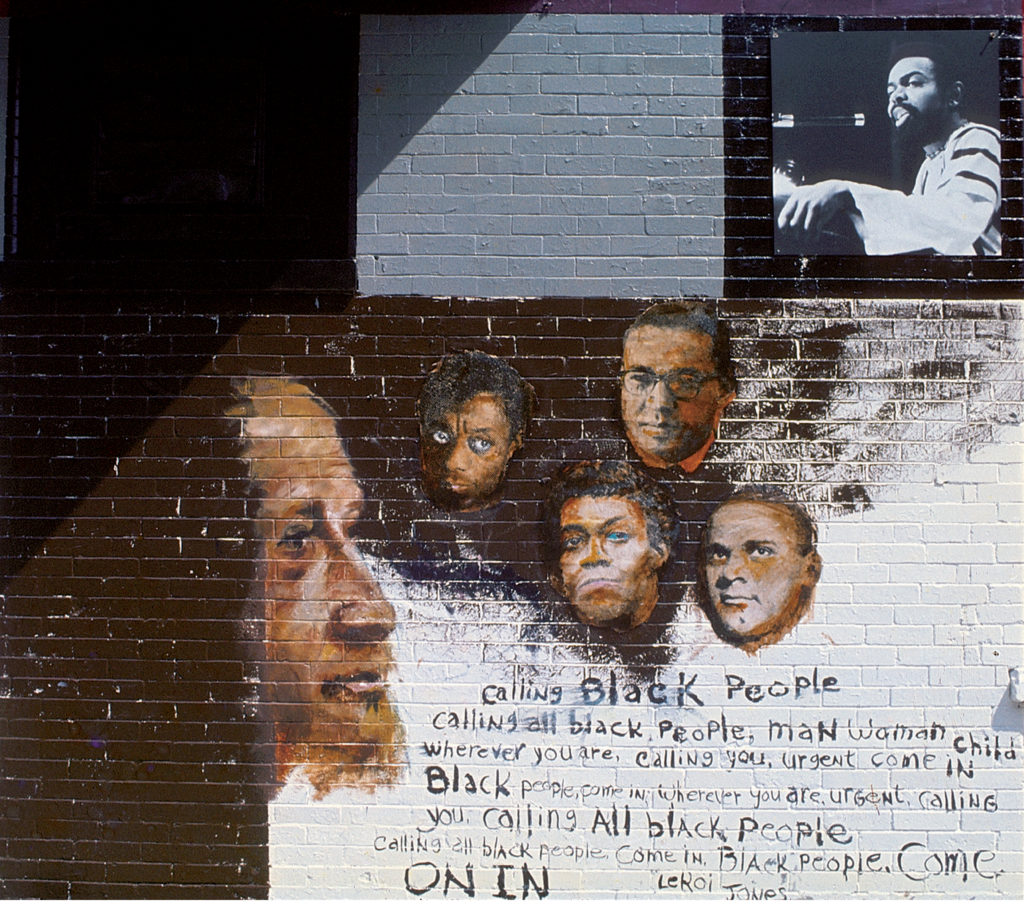

‘The Wall of Respect’ celebrating black literary figures, Chicago, IL, 1967. From left: W.E.B. Dubois, James Baldwin, Lerone Bennett, Amiri Baraka, Gwendolyn Brooks, and John Killen. (Robert Abbott Sengstacke/Getty Images)

The artist’s role in an uprising has always been to address the discontent of the people. Particularly, African American artists have used their platforms to humanize the Black experience and cast uprisings as something not un-American, but inherently American and in line with a longer history of revolt across the Americas, from [the time of] slavery to the present.

Protest is what shapes artists’ identity and moves them to respond. However, the ability to spread [art] to the masses, to individuals or groups that might be unaware of the broader protest, or showing solidarity with grassroots movements, becomes viable to the mainstream whether it’s received well or not.

The historical figures that I examine in my research that respond to uprisings are Gwendolyn Brooks, Henry Dumas, Amiri Baraka, Ben Caldwell, and Sonia Sanchez. What we can learn from these artists today is to give a voice to the unheard and to create a language for the voiceless that not only places their political speech at the fore, but makes the world cognizant of hard truths associated with America’s. and the Western world’s, racial present.

Eddie Chambers

Professor of visual arts of the African diaspora, University of Texas at Austin

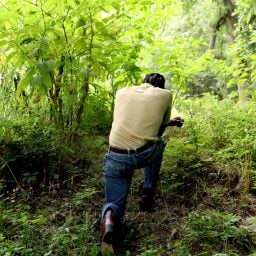

Kimathi Donkor, Coldharbour Lane 1985 (2005). Courtesy of the artist.

Some Black British artists have made important works that speak to, or emerge from, unrest, protest, and what the dominant media characterizes as “rioting.” Artists’ commentary on the “rioting” that took place in cities such as London and Birmingham in the early and mid-1980s includes one of Tam Joseph’s signature works, Spirit of the Carnival, as well as memorable pieces by the late Donald Rodney that made use of an image of a young Black man, stalking his quarry, lit petrol bomb in hand. Kimathi Donkor is another artist whose work countered dominant media narratives of the Black insurrectionist, thereby visualizing not so much “rioting” as resistance.

Paul Rucker

Assistant professor and iCubed research fellow, Virginia Commonwealth University

Paul Rucker, Red Summer. Photo courtesy of the artist.

The last major pandemic, in 1918, was followed by race riots and massacres in 38 cities in 1919, now known as the Red Summer. Early last year, I presented a show by that name at Kenyon College [in Gambier, Ohio], which included newspapers and lynching postcards from the time, as well as original sculptures and performances, anticipating a reprise of this rarely talked-about major historical event.

It’s easy to see a parallel between then and now. Many point to potential positive outcomes from what the COVID-19 pandemic and this year’s global protests against police violence have exposed. But there should be caution along with the optimism and action. After the Red Summer came the Black Wall Street massacre and other forms of retribution: the passing of the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, which banned Chinese immigration and imposed immigration quotas, and the rise of the Ku Klux Klan. Unintended consequences could lead to white supremacy strengthening through today’s events.

Sandipto Dasgupta

Professor of politics at the New School, New York

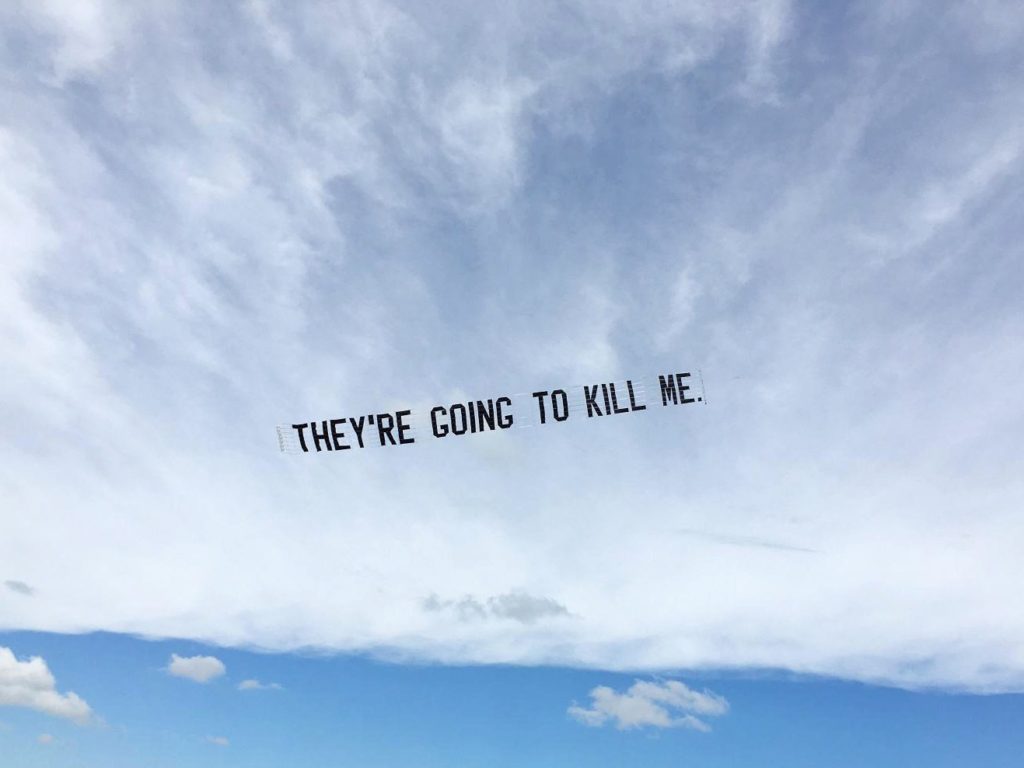

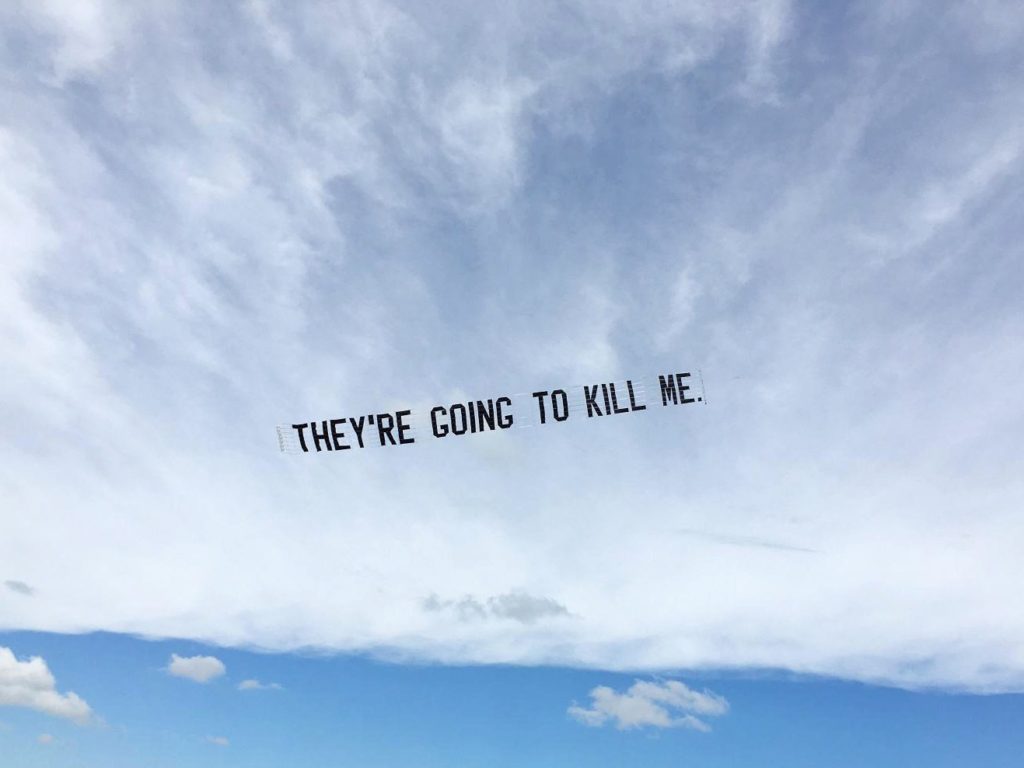

Jammie Holmes, They’re Going to Kill Me (New York City) (2020). Photo courtesy of the artist and Library Street Collective.

We are, every day, saturated with images and texts offering narratives that symbolically gloss over the real contradictions in our society. Times of rebellion crack that narrative. They demand and generate a new language and new ways of seeing. Works of art aligned to rebellions make apparent those contradictions and fissures, and at times produce an image of a better future, both in form and substance. Instead of producing beautiful objects for consumption in the art market, they strive to produce a vision of a different world. When they succeed, they remain impossible to co-opt into the comforting narratives of the powerful.

Sibylle Bergemann, Heike, Allerleirauh, Berlin (1988). Design: Angelika Kroker. © Nachlass Sibylle Bergemann, OSTKREUZ; Courtesy Loock Galerie, Berlin

Most countries behind the Iron Curtain pursued an ideology-based cultural policy which turned finding your own artistic voice or medium or material into an act of subversion already. Pushing experiments with Modernist forms, conceptual photography, film, and performance would often lead to not having institutional exposure. For this reason, the artists had to create their own subversive networks—kind of a managing their visibility for themselves, establishing an artistic and mental independence from official publicity. In my view, the political restrictions even led to a higher degree of freedom compared to societies where “anything goes.” Within that context, tackling the issue of female identity was even more courageous, because the structural machismo prevailed well into the unofficial circles.

Melissa Chiu

Director, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC, and author of Art and China’s Revolution

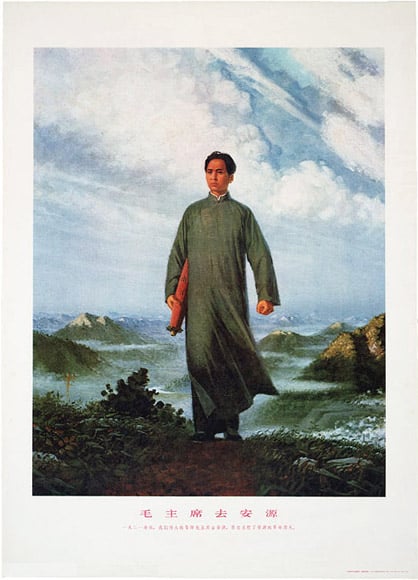

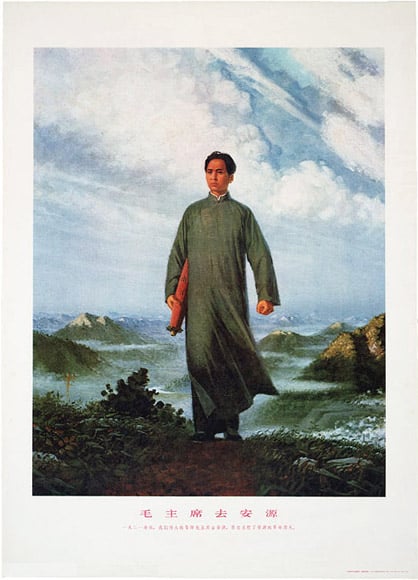

Liu Chunhua, Mao En Route to Anyuan (1967).

The book came from the research I did with Zheng Shengtian on the important period spanning the decade from 1966 to 1976 in China. Artists played a significant role in this movement because a large part of it was about developing a new modern visual vocabulary that symbolized the new modernity espoused by Mao Zedong. Artists created paintings that were then printed into posters for large-scale dissemination of ideas. One work by Liu Chunhua titled Mao En Route to Anyuan was reproduced 900 million times.

It is important to remember that there were artists persecuted at this moment (mostly from an older generation), and a younger generation who were a part of the revolution. The images that younger artists created during this period defined the Cultural Revolution. They showed the political priorities and emphasis, which allowed those values to be circulated in an unprecedented way for that time in history. Looking back, the prevalence of these images of political intent have left an indelible mark on the generation that experienced it, and the art of the time is synonymous with the politics of the time.

Diana Wylie

Professor of history at the African Studies Center, Boston University

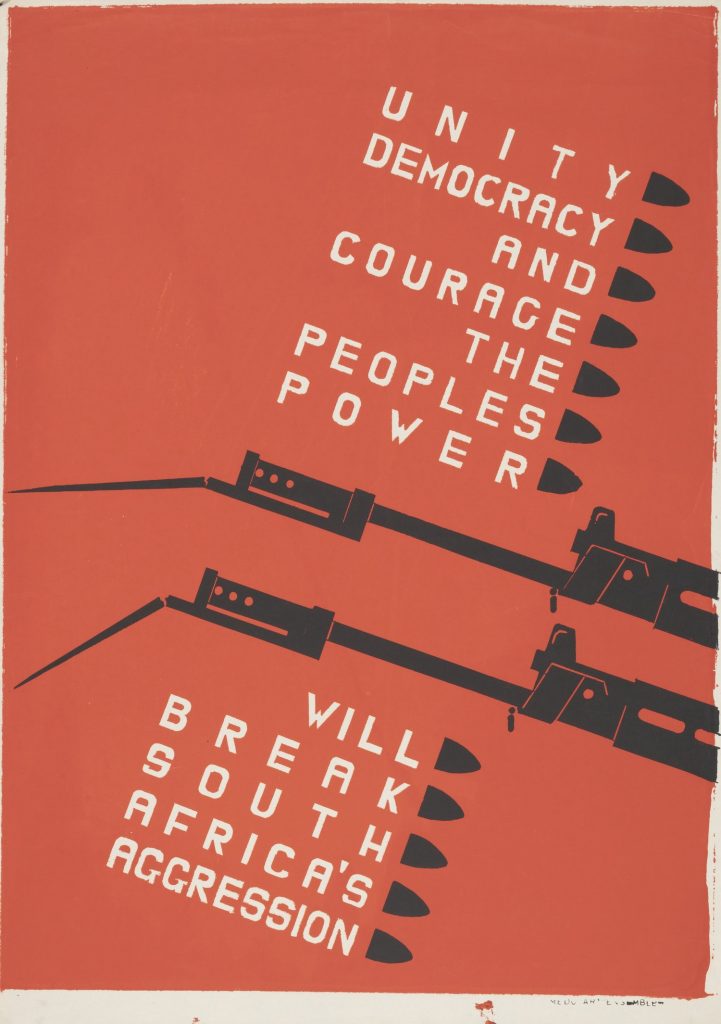

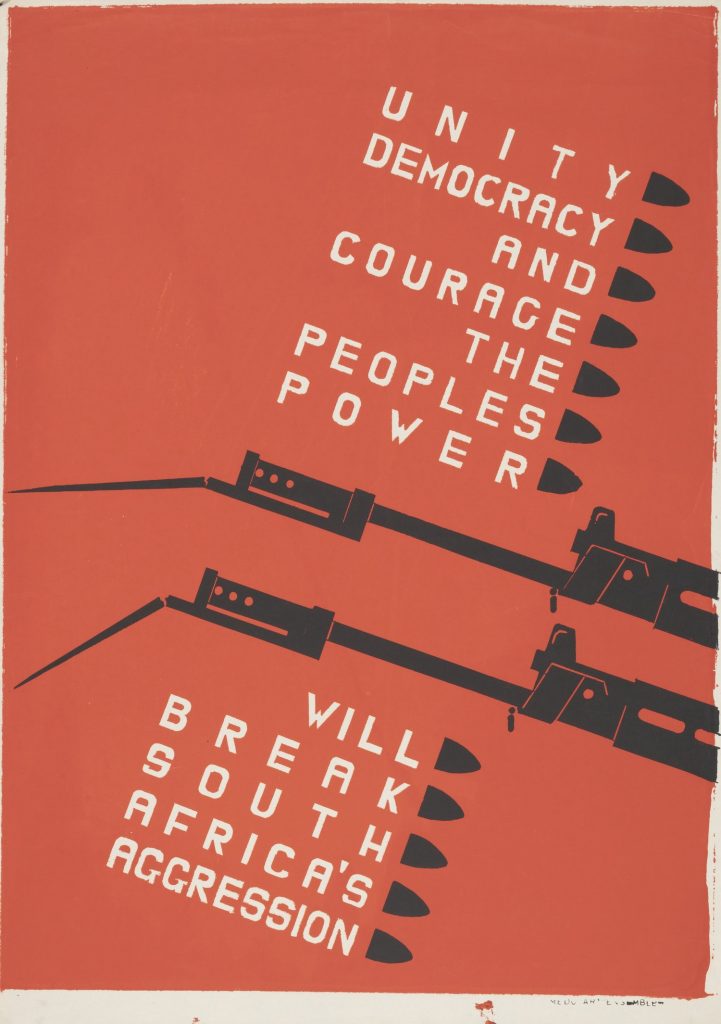

Medu Art Ensemble (Thamsanqa Mnyele), “Unity, Democracy and Courage” (1983) (The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Artworkers Retirement Society © Medu Art Ensemble)

One of the most pressing questions before us in the United States now is how to resolve the tension between our personal visions and needs, on the one hand, and the demands of being a member of a community, on the other. Even a popular television series has recently broached the question, “What do we owe other people?” I had the privilege of knowing a South African artist—Thami Mnyele (1948–85)— whose life was strung up between the two poles of being absorbed in his own hopes and fears and of being useful to his community. Mnyele dealt with the dilemma by spending his first decade as an active artist expressing with delicacy his feelings while living under apartheid. Then he joined the African National Congress and put his gifts at the service of a movement fighting for liberation from white supremacy. The ANC gave him the daunting chance to sacrifice himself—his vision and his life— for the idea of a greater good. Mnyele’s art opens a window on the double-edged opportunity—for creativity and for sacrifice—afforded by a time of profound social crisis, not unlike the one we’re living in now.