Art History

Why Grant Wood’s ‘American Gothic’ So Rankled Iowans

Is the famous painting a celebration of Midwestern perseverance? Or a mockery of a culture stuck in time?

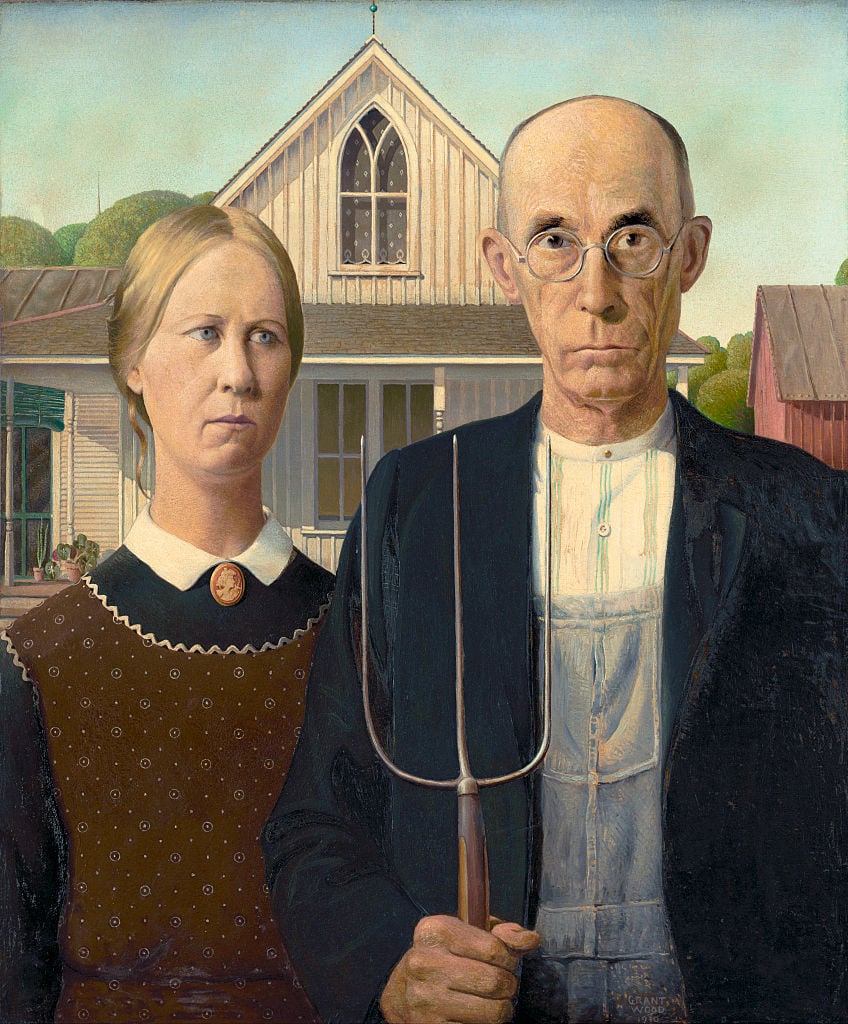

Grant Wood’s American Gothic (1930) is a painting that needs no introduction. It’s a deceptively simple work of art—a seemingly straightforward portrait of an old farmer and his daughter, pictured in front of their country house (based on a real building the painter encountered in Eldon, Iowa), their faces hardened by a lifetime of labor.

Still, to dismiss American Gothic as a simple piece of portraiture would be a mistake. Clear though its composition and subject matter may be, Wood, a Midwestern Regionalist master, took numerous creative liberties. From the pitchfork in the old farmer’s veined hand to the embroidery on his shirt—which, on close inspection, matches the tool he’s holding—this is not a faithful representation of life, but a gothic construction that sends a specific message.

What this message is depends on who you ask. While Wood seldom talked about the meaning of his work, his silence did not stop others from speculating. When American Gothic was first exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago, where it still resides, it met with a divided reception. While some praised Wood’s depiction of a hardworking Puritan family, others, particularly Iowans, criticized what they interpreted as a mean-spirited caricature of the Midwest.

Visitors to the Art Institute of Chicago viewing Grant Wood’s American Gothic. Photo: Robert Nickelsberg/Getty Images.

Iowans were more critical of the painting. According to Slate, readers of one of the state’s local newspapers, the Cedar Rapids Gazette, thought the painting’s subjects looked like “pinched, grim-faced, puritanical Bible-thumpers,” a singular, misleading representation of their state. Wood, in a rare display of public relations, disagreed, insisting the painting wasn’t ironic. He wrote he “had to go to France to appreciate Iowa,” adding that “people who resent the painting are those who feel that they themselves resemble the portrayal.”

To make matters more complicated still, a close reading of American Gothic yields evidence in support of both interpretations. Those who feel that Wood is poking fun at his rural subjects point to the pitchfork (a rake in earlier drafts of the painting) in the hands of the old man—standard farming equipment, to be sure, but also a recognizable symbol of the devil and evil in general.

Aside from Biblical imagery, the similarities between American Gothic and early American photography, in which 18th- and 19th-century subjects often posed in front of their houses, suggest that Wood believed these two Iowans to be stuck in time: a common criticism leveraged against the country’s flyover states.

But Wood’s representation of his subjects could also be read as positive. Those early American photographs showed people displaying assets they gained by working long and hard. In this sense, the painting could be read as a celebration of rural American values, of perseverance leading to prosperity even in the depths of the Great Depression.

This is the position adopted by art historians like Wanda Corn, author of Grant Wood: The Regionalist Vision (1983), who noted that the snake plant, one of the plants depicted in the painting, was popular among pioneers and frontierswomen for its toughness, a quality shared with its hardy, determined cultivators.

Although the message of American Gothic is ambiguous, the negative impression it made on Iowans would haunt Wood (an Iowa native himself) for the rest of his life. The artist maintained a tense relationship with his colleagues at the University of Iowa, where he taught for seven years, suggesting the already famous painting rubbed some fellow faculty members the wrong way.

It appears this estrangement persists into the present as, despite being one of the university’s more famous faculty members, his name is nowhere to be found on campus grounds.

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history.