Art World

Art Bites: Salvador Dalí’s Nuclear Mysticism Phase

The theory was a reaction to the devastation wrought on Japan during World War II.

The theory was a reaction to the devastation wrought on Japan during World War II.

Verity Babbs

After the “Little Boy” and “Fat Man” nuclear bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945, Salvador Dalí became fascinated with atomic theory. In 1973, he reflected that the explosion in Hiroshima “shook me seismically. Thenceforth, the atom was my favorite food for thought.” This new interest in the atomic kickstarted a new phase of his career, a framework he called Nuclear Mysticism, which embodied a philosophical approach to quantum physics.

Nuclear Mysticism examined the link between the energy of the mind and the physical matter of the body, and the unbreakable energy-bond between all things on earth. After the mass destruction seen during World War Two, Nuclear Mysticism offered a reunifying resolution. In 1976 the artist wrote that “a divorce has come about between physics and metaphysics. We are living through an almost monstrous progress of specialization, without any synthesis.” While exploring these cosmically unifying concepts Dalí made a return to the Catholic faith of his mother, having previously shared his father’s atheism.

Theories around quantum physics and molecular biology found their way into Dalí’s paintings from around 1950. These new works often featured spheres representing particles and cubes which appeared to have been atomized. His artworks ceased to be so personal, unlike his early work which examined his own dreams.

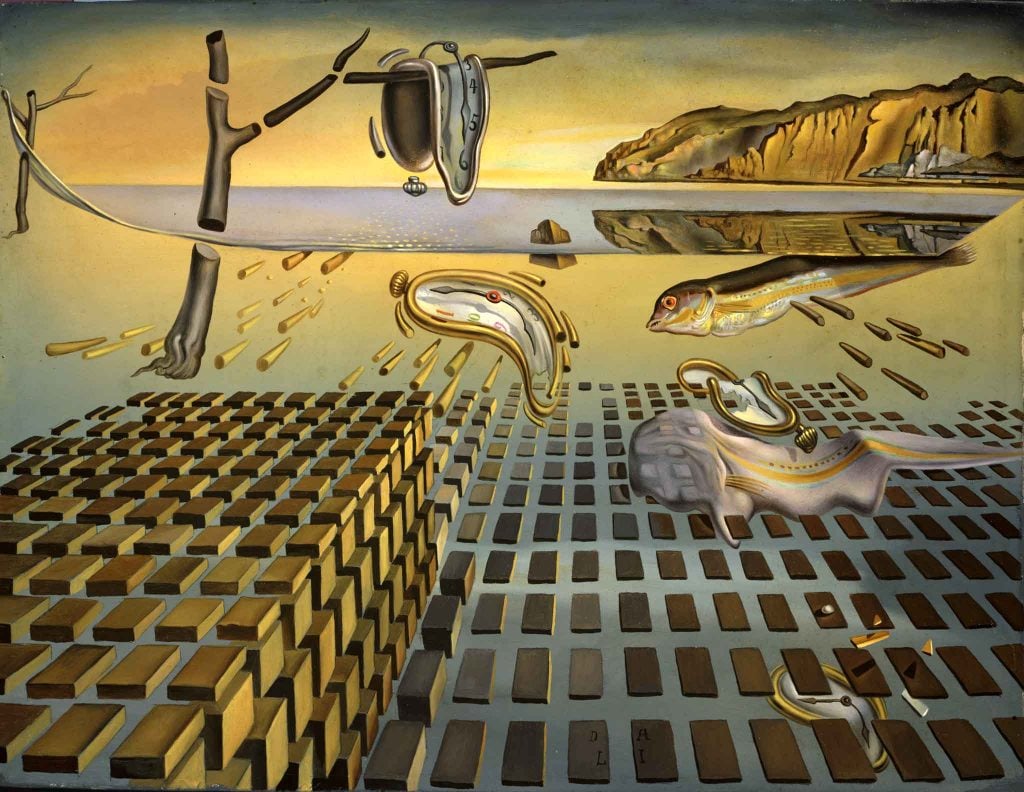

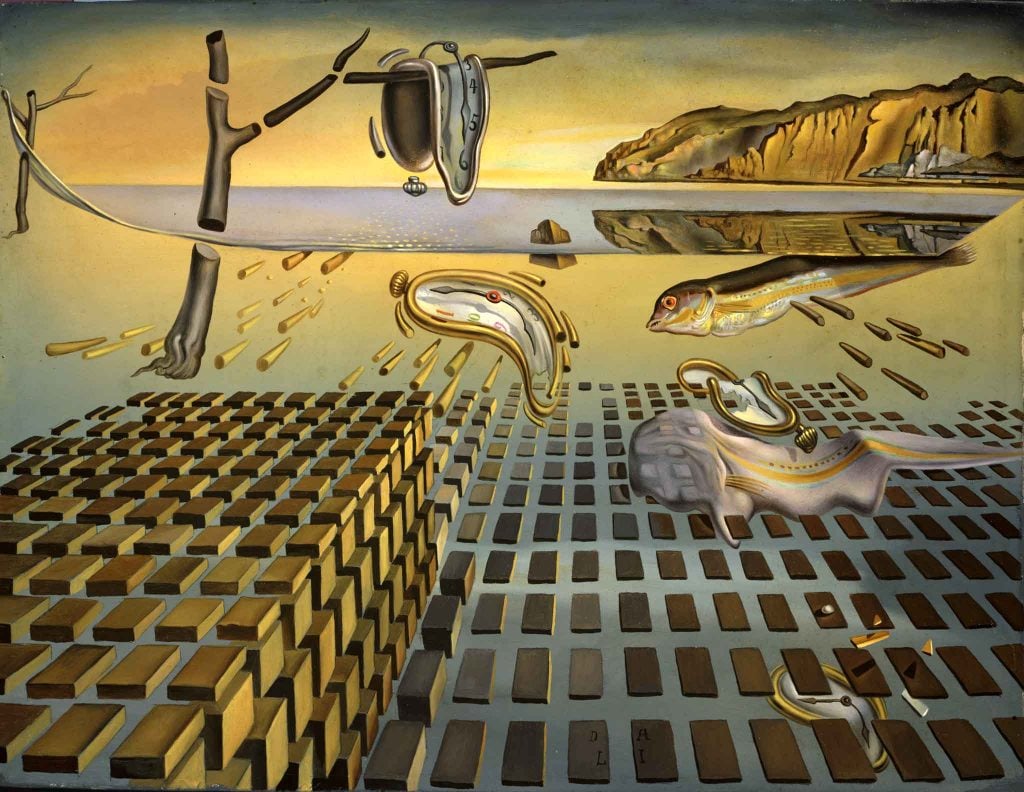

The artist had previously made work using his “Paranoid Critical Method,” in which the artist would induce a state of paranoia and create his works guided freely by the subconscious. This system had a clear methodology, something which his Nuclear Mysticism era lacked. In 1954 he recreated his Paranoid Critical masterpiece The Persistence of Memory (1931) as The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory (1952-4) in which the landscape and melting clocks—which have become a famous symbol for the surrealist artist—are broken up and dispersed through the negative space.

Monumental works from the Nuclear Mysticism phase include The Railway Station at Perpignan (1965) which showed the stop in southern France as the centre of the universe. Various figures are suspended in the air, including two representations of Dalí and Christ on the cross in the centre. In 1963 the artist had visited the station, and described having a “precise vision of the constitution of the universe,” experiencing what is called “cosmogonic ecstasy.”

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history. These delightful nuggets shed light on the lives of famed artists and decode their practices, while adding new layers of intrigue to celebrated masterpieces.