Art World

Art Bites: The ‘Psycho’ House Was Modeled After This Hopper Painting

Both artists explored the loneliness that results from modernization.

Alfred Hitchcock once told fellow filmmaker François Truffaut that “nine out of 10 people, if they see a woman across the courtyard undressing for bed, or even a man puttering around in his room, will stay and look; no one turns away and says, ‘It’s none of my business.’ They could pull down their blinds, but they never do; they stand there and look out.”

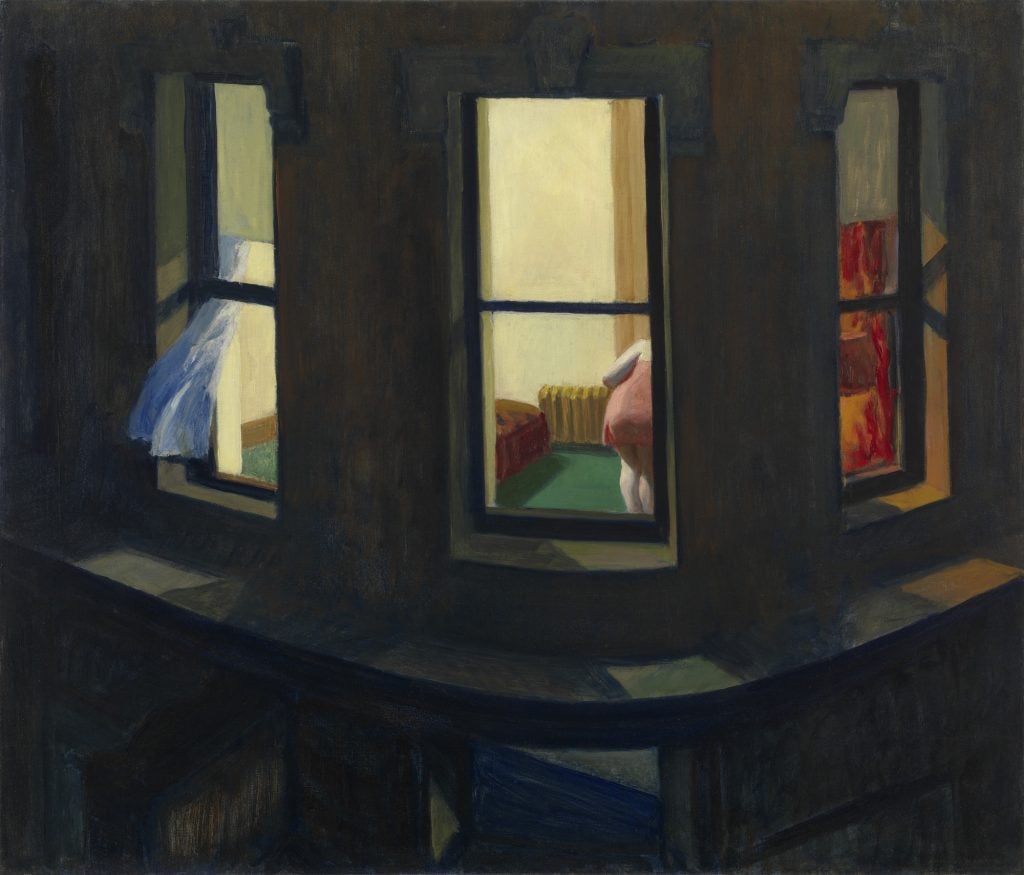

A similar statement can be found in the paintings of American artist Edward Hopper, which frequently depict figures inside their apartments as seen through large windows. Hopper was so fascinated with the way windows allow outsiders to peek into people’s interior lives that he seldom bothered to paint curtains, blinds, or even glass.

Knowing this, it should come as no surprise that Hopper’s paintings had a considerable influence on Hitchcock’s 1954 mystery thriller Rear Window. The film, about an injured news photographer who believes he witnesses a murder while spying on his neighbors with a pair of binoculars, is packed with voyeuristic scenes that look like they were painted by Hopper himself.

Edward Hopper, Night Windows (1928). Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Hopper also left his mark on Psycho, arguably Hitchcock’s most beloved film. Released in 1960, it follows a secretary (played by Janet Leigh) who absconds with $40,000 of her boss’s money. On the road, she makes the mistake of stopping at a run-down motel operated by one Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins), who lives in a nearby house, supposedly with his mother.

Actor Anthony Perkins as Norman Bates in the film Psycho (1960). Photo: Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images.

Fans of Hopper might recognize the Victorian-style mansion from a 1925 painting titled House by the Railroad. It shows a similarly solitary building looming over a small brick wall, itself based on an 1885 residence in Haverstraw, New York. Located not too far from Hopper’s birthplace, it’s wedged—fittingly—between a railroad and a cemetery.

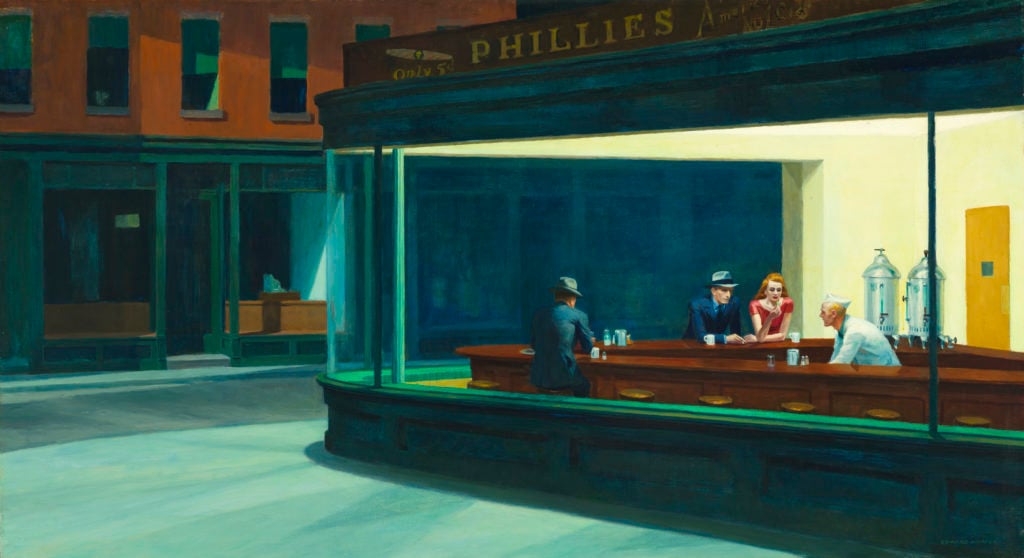

Fittingly, because both Hopper’s paintings and Hitchcock’s films explore the extent to which progress and urban modernization have made the world lonelier and, as a result, capable of acts of explosive, irrational violence. Like the lonely diners sharing the silence in Hopper’s 1942 painting Nighthawks, the homicidal Bates lives in complete isolation from the rest of society, interacting with no one except his abusive mother (who—spoiler alert!—exists only in his mind).

Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks, 1942. Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

In a documentary on the film’s production, Psycho screenwriter Joseph Stefano said that if the character of Bates were a painting, he “would be painted by Hopper.” He added that Perkins “must have known what it was like to be trapped. In some way, somehow, he knew what trapped meant, just as I did.”

Of course, Hopper also fits with Psycho because Bates, much like the protagonist of Rear Window, is a voyeur, arguably the most famous in cinematic history. Etched into many a moviegoer’s brain is the scene where he, knife in hand, sneaks up on the poor secretary as she showers. If Hopper’s quiet, prurient images represent the calm before the storm, Psycho shows the carnage that could potentially follow.

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history. These delightful nuggets shed light on the lives of famed artists and decode their practices, while adding new layers of intrigue to celebrated masterpieces.