Art World

Art Bites: What Was Leonora Carrington’s Surrealist Survival Kit?

The painter proposed these kits to help anyone, artist or not, survive modern society

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history. These delightful nuggets shed light on the lives of famed artists and decode their practices, while adding new layers of intrigue to celebrated masterpieces.

Humans subsist on food and water, of course, but famed Surrealist Leonora Carrington liked to believe that we need alluring stones and feathers that flutter in on the wind just as much. Carrington conceived of “Surrealist survival kits” to help anyone, artist or not, survive modern society. She shared the concept with colleagues like Penelope Rosemont, who founded the Chicago Surrealist Group in 1966 and penned Surrealist Women: An International Anthology in 1998. There, Rosemont recounted that Carrington repeatedly mentioned these proposed kits during their many meetings in Chicago between 1989 and 1992.

Each kit contains “a collection of poetic, magical, talismanic objects, along with images and other ‘Surrealist things,’” Rosemont told Joanna Moorhead in Surreal Spaces: The Life and Art of Leonora Carrington (2023). “A kit might include a feather, a pebble, a piece of glass, some verses from a poem.” Each one is as unique to its owner as their fingerprint. It’s all about resonance. Rosemont wrote that such eccentric collections could offer “a breath of magical fresh air” and “enable us to get through these terrible times.”

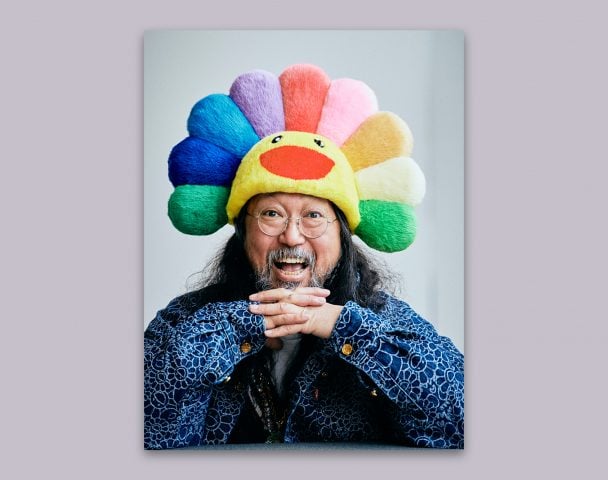

Leonora Carrington, Artes 110 (c. 1942). Courtesy of NFU Wolfsonian.

Carrington produced dozens of writings and paintings throughout her 94 years. Her artworks and life choices alike balanced self-preservation with whimsy. Carrington extricated herself from her dictatorial father and needy lovers like Max Ernst. She escaped forcible commitment to a mental institution and lived to write a book about the experience. Carrington safeguarded her freedom in an era where many women simply hoped they’d be commanded by someone competent.

The Surrealists that Carrington fell in with during the 1930s considered women, first and foremost, to be muses. But even Dalí, who wrote in the half-serious 1934 essay, “The New Colors of Spectral Sex Appeal,” that the attractiveness of the modern woman would come down not to her intellect or creativity but rather to “the disarticulation and distortion of her anatomy,” came around to call Carrington “a most important woman artist.” The Surrealists came to regard Carrington as a sort of witch. It’s no wonder, then, that her proposed Surrealist survival kits resemble little traveling altars that should fit into a cloth no larger than what a child would use to transport marbles.

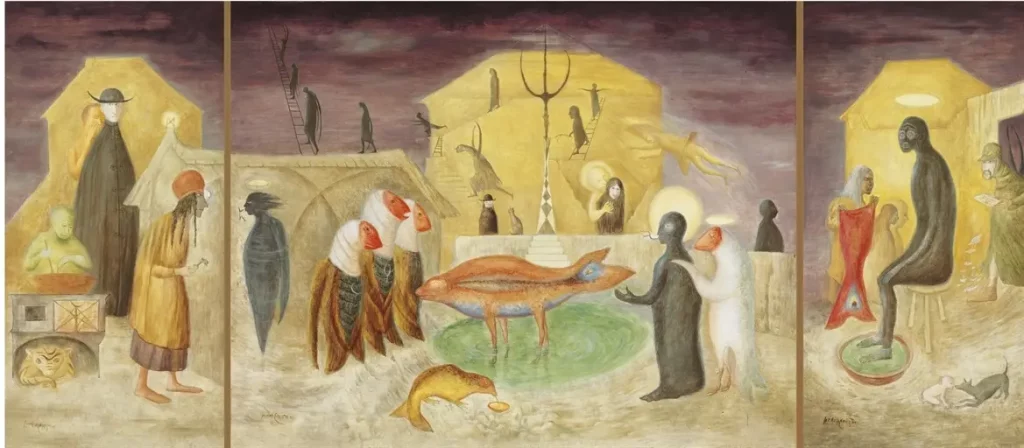

Leonora Carrington, Nativity (triptych) (1989).

There are still active surrealist groups around the globe. Members from the Surrealist London Action Group (also known as SLAG), as well as the Stockholm Surrealist Group, convened in Athens the same month that Carrington passed away for a get-together that had been a year in the making. There, the international surrealists engaged in a group exercise assembling Carrington’s prescribed survival kits, “some elaborately prepared from beloved fetish objects, some improvised from detritus found on the spot, some individual, some collaborative,” as one adherent’s post-meeting blog post recalled. They invited Athenians to behold and discuss the kits alongside poetry readings, live music, and more.

“As we reflected together on the unfolding results of our game, we understood that what made the kits significant was not the personal collection of ‘favorite things’ by individuals,” the post said. “Our survival Kit was not the objects themselves, but the ability to find and transform them. Surrealism is our survival kit.”